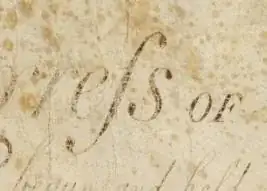

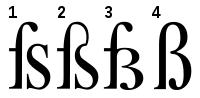

The ß glyph is a lowercase letter that represents a ligature between a long s (ſ) and a round s, and is still used today in (some versions of) German. Its uppercase equivalent is two characters instead of one: SS.

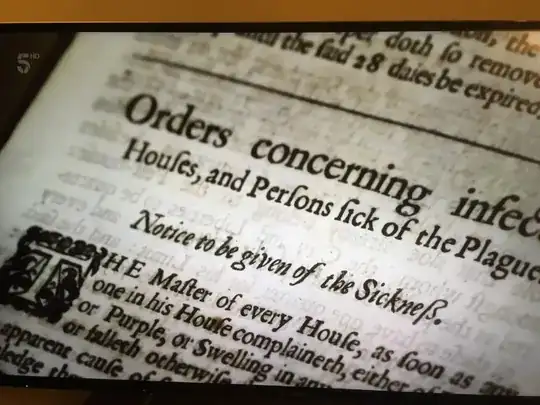

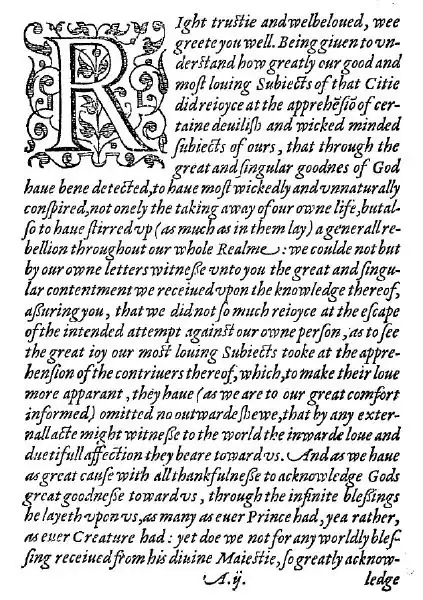

It was apparently also once used in just the same way English, but I cannot find just exactly when or where. Was it used in manuscripts only, or in printed books too? During what time period would this have run? If in print, was it done only in blackletter faces in English, or was it also done in the less German-looking ones?

Somewhat related is the question What animal is a “weefil”?.

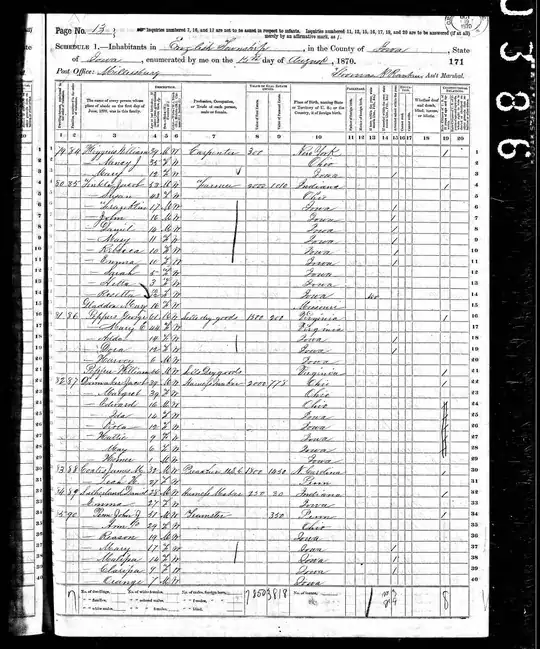

Longhand "sharp s" was still utilized during the late 19th century in the American Midwest. As you can see from the attached 1870 US Federal Census, the census enumerator on lines 38 and 39 scribed "Melissa" and "Clarissa" as Malißa (sic) and Clarißa.

Longhand "sharp s" was still utilized during the late 19th century in the American Midwest. As you can see from the attached 1870 US Federal Census, the census enumerator on lines 38 and 39 scribed "Melissa" and "Clarissa" as Malißa (sic) and Clarißa.