Dictionary discussions of 'warm the cockles'

Dictionaries of word and phrase origins published in the past century seem split on the derivation of "warm the cockles of [one's] heart." Here are six entries for the phrase from various sources.

From Christine Ammer, The American Heritage Dictionary of Idioms, second edition (2013):

warm the cockles of one's heart Gratify one, make one feel good, as in It warms the cockles of my heart to see them getting along so well. This expression uses a corruption of the Latin name for the heart's ventricles, cochleae cordis. {Second half of 1600s}

From John Ayto, Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms, third edition (2009):

warm the cockles of someone's heart give someone a a comforting feeling of pleasure or contentment. This phrase perhaps arose as a result of the resemblance between a heart and a cockleshell.

From Robert Hendrickson, The Facts on File Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins, fourth edition (2008):

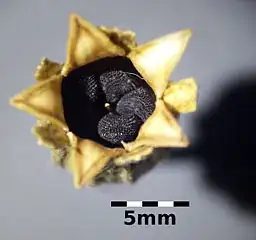

warm the cockles of one's heart. The most popular explanation for the cockles here says that late-17th-century anatomists noticed the resemblance of the shape of cockleshells, the valves of a scallop-like mollusk, to the ventricles of the heart and referred to the latter as cockles. Whether this is the case or not, cockles isn't use much anymore except in the expression to warm the cockles of one's heart, to please someone immensely, to evoke a flow of pleasure or a feeling of affection." Behind the expression is the old poetical belief that the heart is the seat of affection.

From Longman Dictionary of English Idioms (1979):

warm the cockles of someone's heart coll[oquial] to produce a warm feeling of health and contentment in a person, esp. by means of alcohol: drink this! It'll warm the cockles of your heart on a cold night like this || 'it warms the cockles of my heart when I hear the old war songs,' said the old soldier ... {Perhaps from a comparison between the shape of the heart and a cockleshell

From William Morris & Mary Morris, Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins (1962):

cockles of the heart You have often heard the phrase warm the cockles of one's heart, but these cockles have nothing to do with the cockles and mussels Sweet Molly Malone used to sell.

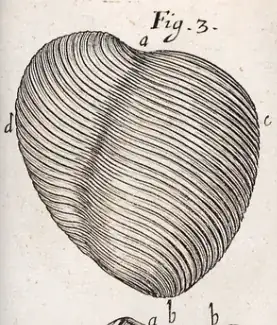

The cockles of the old ballad are what the dictionaries call "edible bivalve mollusks"—shellfish, to you and me. In appearance they are unlike our scallops, having a somewhat heart-shaped, ribbed shell.

The cockles of your heart, on the other hand are the ventricles and thus, by extension, the innermost depths of one's heart or emotions. The word comes from the Latin phrase cochleae cordis, meaning "ventricles of the heart," while the shellfish cockle comes from the Latin conchylium, meaning conch shell.

From Ernest Weekley, An Etymological Dictionary of Modern English (1921):

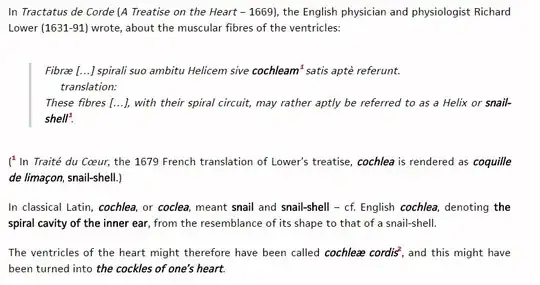

cockle2. Shell. F. coquille, from VL. coccylium, L. conchylium, G. κογχύλιον, from κόγχη, whence L. concha, VL. cocca, origin of F. coque, shell (of egg). ... The cockles of the heart are explained (1669) as for the related cochlea (q.v.), winding cavity. Hot cockles, a game in which a blindfolded person has to guess who slaps him, occurs in in Sidney's Arcadia. It is app[arently] adapted from F. jeu de la main chaude, but cockles is unexplained.

Weekley's entry for cochlea is as follows:

cochlea. Cavity of ear. L., snail, G. κοχλίας. From shape.

So it appears that your choice of derivations comes down to a choice of mollusks: gastropod or pelecypod.

Supplementing these authorities are two earlier references. First, J. Dixon makes the cochleae cordis argument in an issue of Notes and Queries (July 9, 1887), and A.F. Chamberlain argues for the cockle weed as the original figure involved in "cockles of the heart" in an issue of American Notes and Queries (May 4, 1889).

Meanings of 'cockle' in early dictionaries

John Kersey, Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum: Or, A General English Dictionary (1708) offers these definitions for cockle:

Cockle, a kind of Shell-fish ; also a Weed otherwise call'd Corn-rose.

To Cockle, to pucker, wrinkle, or shrink, as some Cloth does.

Cockle-stairs, winding-Stairs.

The mystery of why winding stairs would be called cockle-stairs is perhaps answered by Kersey's definition for cochlea on the same page:

Cochlea, (L.) the Cockle, a Shell-fish; the Sea-snail, or Periwinkle : Also a Screw, one of the Six Mechanick Powers, or Principles : In Anatomy, the Hollow of the inner part of the Ear.

Here we see a degree of confusion in the use of cochlea to refer to both a bivalve (the cockle and a snail (the periwinkle). If the confusion extended in the opposite direction, it would be easy to explain cockle-stair as having originated as cochlea-stair after the periwinkle's winding shell. Edward Phillips, The New World of English Words, or a Generall Dictionary (1658) includes the shell-fish and weed definitions of cockle, but renders the architectural term for winding stairs as cocle-stairs. Elisha Coles, An English Dictionary: Explaining the Difficult Terms... (1692) includes an entry for cockleary, meaning "pertaining to winding stairs."

Thomas Dyche & William Pardon, A New General English Dictionary (1735) reports that the verb sense of cockle is "To shrivel, gather or shrink up, to pucker like an ill-sown seam, &c."—suggesting a similarity to a cockleshell's ribbing. Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) confirms this:

To Cockle. v. a. {from cockle.} To contract into wrinkles like the shell of a cockle.

But Johnson is less sure of the meaning of the adjective cockled, which he finds in Love's Labour's Lost:

Cockled. adj. {from cockle.} Shelled; or perhaps cochleate, turbinated. [Cited occurrence:] Love's feeling is more soft and sensible,/ Than are the tender horns of cockled snails. Shakespeare.

John Kersey, A New English Dictionary, fourth edition (1739) omits the entries for cochlea and cockle-stairs but adds an entry for hot-cockles:

Hot-Cockles, a kind of Sport.

As we saw in Weekley's Etymological Dictionary, the sport consists of having blindfolded subjects try to guess who just slapped them.

Early instances of 'the cockles of [one's] heart'

As tchrist notes in his answer, one very early instance of the phrase appears in John Eachard, "Some Observations upon the Answer to an Enquiry into the Grounds & Occasions of the Contempt of the Clergy" (1671/1685 [fifth edition]):

But of all Strategems that he [a critic who published an answer to Eachard's original publication, The Grounds and Occasions of the Contempt of the Clergy and Religion Enquired Into] makes use of, to shew how vain and successless all my endeavours were likely to be; that certainly argues the most of close and thick thinking, which he lucks upon (p. 12.) Nay, says he, I will venture farther a little to make it appear (and indeed if there were ever Venture made, this was one) that Ignorance and Poverty are not the only grounds of Contempt; for some Clergy-men are as much slighted for their great Learning, as others are for their Ignorance. Now, although he says in his Preface, that he would not much boast of convincing the world, how much I was mistaken in what I undertook; yet, I am confident of it, that this Contrivance of his did inwardly as much rejoyce the Cockles of his heart as he phansies, that what I writ did sometimes much tickle my Spleen. But wherein, I pray, Sir, are they slighted?

But earlier than the earliest identified instance of "the cockles of [one's] heart" is an instance of "the cockles of [one's] head." From Guillaume Du Bartas, "The Decay in Josuah Sylvester's translation of Works of Du Bartas (1608/1641):

Jezebel:/ The Queen had inkling: instantly she sped/ To curl the Cockles of her new-bought head:/ The Saphyr, Onyx, Garnet, Diamond,/In various forms cut by a curious hand,/ Hang nimbly dancing in her hair, as spangles:

Here the "Cockles" appear to be ringlets, perhaps (in this case) on a wig. William Whitney, The Century Dictionary (1899) partially confirms that view, citing Du Bartas's verse in support of its definition 4 of cockle: "A ringlet or crimp." But a ringlet arguably suggests a snail, and a crimp arguably suggests the ridges of a bivalve shell, so we haven't really clarified which creature "cockles of hair" invokes.

Another early instance of "the cockles of [someone's] heart" again uses rejoyce. From Thomas Brown, "Dialogue II" (ca. 1688–1690), from A Collection of All the Dialogues Written by Mr. Thomas Brown (1704):

Crites. Why truly, Mr. Bays, I must needs own that 'tis writ with more Caution than generally such kind of Lives are, and as for the Language and the Ornaments of the Stile, I have nothing to except to them, for, without any more Ceremony, they are extremely fine, both in the Original and in the Translation.

Bays. Nay, now you Rejoyce the Cockles of my Heart, honest Mr. Crites; oh I love dearly to have my pieces commended, and all that, by a Person of Understanding: I'gad I do, Mr. Crites, 'tis the greatest refreshment in the World. Prithee, dear Rogue, let me hugg thee to pieces. Come, I'll give thee a Dish of Tea for this———

The same Thomas Brown (who died in 1704) is responsible for one of the earliest Google Books instances where cockles of the heart are heated—in fact, kindled. From "The Virgin's Answer to Mrs. Behn," in Letters from the Dead to the Living (1702/1707):

First, were I to give my self Liberty (as whether I do or no, is no matter to any Body) I would always bestow my Favours upon those above me, and those beneath me, and never be concern'd with any Man upon an equal footing ; and these are my Reasons: Suppose the vicious Eyes of a great Man are fix'd upon me, and my charms should kindle a Love-Passion in the Cockles of his Heart ; he Writes, Chatters, Swears and Prays, according to Custom in such Cases, I still defend the Premises, by a flat verbal denial ; but at the fame instant, encourage him in my Looks, and am always free to oblige him with my Company, till by this sort of usage, I make him sensible down-right Courtship will never prevail; and that the Citadel he besieges, is not to be surrender'd without bribing the Governess: ...

Nevertheless, Francis Grose, Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, second edition (1788) cites the "rejoice" version of the expression:

COCKLES. To cry cockles ; to be hanged : perhaps from the noise made whilst strangling. Cant.—This will rejoice the cockles of one's heart ; a saying in praise of wine, ale, or spiritous liquor.

And the use of rejoice appears at least as late as George James, Pequinillo, volume 1 (1852):

Her [Kit's] services were not forgotten by Ludlow and his wife; and, as they went out, after bidding Kit Markus a hearty farewell, the former slipped a crown piece into her hand, which rejoiced the cockles of her heart, more than most things ever did in life ; for it was the first she ever had, and she knew the bitter taste of poverty.

Google Books also turns up instances of "cheer the cockles of his heart" (1816), "comfort the cockles of his heart" (1821), earlier than the earliest instance I could find in Google Books or Elephind for "warm the cockles of [one's] heart." The earliest seven such instances are as follows.

From Richard Penn Smith, The Triumph at Plattsburg (1830), in Representative American Plays (1916):

ANDRE [MACKLEGRAITH]. Corporal Peabody, it warms the cockles o' my heart to see your good natured face at this present speaking, though you ken weel enow, that the time ha' been, and that na lang syne, when I would ha' preferred your room to your company any day in the week, and ha' been the gainer by it.

From Frederick Marryat, Jacob Faithful, serialized in The Metropolitan (February 1834):

"There now, master, there's a glass o' grog for you that would float a marlingspike. See if that don't warm the cockles of your old heart."

"Aye," added Tom, " and set all your muscles as taught as weather backstays."

From W.H. Ainsworth, Jack Sheppard, serialized in Bentley's Miscellany (February 1839):

"Give me the brandy, and I'll tell you," replied Wood.

"Here, wife—hostess—fetch me that bottle from the second shelf in the corner cupboard.—There, Mr. Wood," cried David, pouring out a glass of the spirit, and offering it to the carpenter, "that'll warm the cockles of your heart. Don't be afraid, man,—off with it. It's right Nantz. I keep it for my own drinking," he added in a lower tone.

From "English Extracts: The Stomachs of London," reprinted from Blackwood's Magazine in the Sidney [New South Wales] Morning Herald (December 27, 1842):

Truly, ravenous reader, it is a goodly stomach that same Smithfield; like our own, empty as a gallipot the greater part of the week, but filled even to repletion upon market days. In our case, you will understand market day to be that when some hospitable Christian, pitying our forlorn condition, delights our ears, warming the cockles of our heart with a provoke; when, he assured, we eat and drink indictively, like an author at his publisher's!

From "A Windfall for the 'Young 'Un'" from the New York Spirit of the Times, reprinted in the Ottawa [Illinois] Free Trader (December 11, 1846):

To my honored Senior (whom I set down in my category as my legitimate "dad,") I would refer you for father particulars. He is tenacious of the character of his progeny and loves me ; I would commend him to you, for it will warm the cockles of his old heart to learn that the "Young 'Un" is in luck.

From "Lord John Russell's Bowl of Bishop," in Punch, or the London Charivari (January 1848):

At this usually inclement season of the year, the cheerful mug of egg-flip and the comforting tumbler of hot-spiced elder cordial are in great request, as the means of raising low spirits and warming the cockles of the chilled heart. Perhaps, however, both egg-hot and elder: wine must yield in their elevating and invigorating properties to a good Bishop.

From "Local Intelligence," in Bell's Life in Sydney [New South Wales] and Sporting Reviewer (March 17, 1849):

"IF YOU DOUBT WHAT I SAY TAKE A BUMPER AND TRY."—The words of this song occurred to us last evening, when we paid a visit to our friend Samuells, the worthy host of the Liverpool Arms, at the corner of Pitt and King-streets, upon which occasion we wound up with a glass of the creamy, which warmed the cockles of our heart. Not content with administering this comfort, he insisted upon cooking us a chop, and washing it down with a first-rate glass of Byas's best, not forgetting a drop of the real pale Cognac to prevent any rebellious qualms in the lower regions.

And from [Anonymous], Harley Beckford, volume 3 (1849):

"Ay, brandy's the stuff for heroes, French, Dutch, or English! Fill up, and I'll mate you!" cried John. The glasses were filled, rung together at the rims, and emptied at the word "Fire." "Hah!" said he, smacking his lips with extreme relish, and looked lovingly at the remainder."It warms the cockles of one's heart."

Conclusions

English-language writers have mentioned "the cockles of [one's] heart" since at least 1671, when John Eachard, in the course of a screed directed at an opponent in a controversy over religious doctrine, asserted that a "contrivance" that his opponent had devised "did inwardly ... rejoyce the Cockles of his heart"—an experience that Eachard suggests is similar to the physiological effect that his own writing has on him, namely, that it "did sometimes much tickle my Spleen." From this I infer that Eachard may have conceived of cockles not as a metaphorical allusion to cockleshells or to the cockle weed/corn-rose/darnell/field campion, but as a description of a winding passageway—that is, a cochlea.

Today, we associate the word cochlea exclusively with the inner ear, and John Kersey's entry for the term in his 1708 Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum does cite that as the anatomical sense of the word. But cochlea also might refer to either the cockleshell (a bivalve) or the periwinkle (a sea snail)—the one notable for its radiating ridged surface and somewhat heartlike shape, and the other for its turbinate form and winding interior. Moreover, dictionary entries (over the course of 200 years) for cockle-stairs or cocle-stairs (meaning winding stairs) strongly suggest that cochlea made the jump to cockle in at least one area of English.

In Google Books searches, the earliest verbs associated with "the cockles of [one's] heart" are rejoice (1671), cheer (1816), and comfort (1821), with warm first appearing in 1830. By then, the term "cockles of [one's] heart" had fallen into disfavor among cultivated English speakers, as Francis Grose points out in his Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1785), where he describes "rejoice the cockles of one's heart" as part of a cant phrase in praise of alcoholic drink. Of the first eight instances of "warm the cockles of [one's] heart" that I found (all from the period 1830–1849), five clearly involve drinking some type of alcoholic beverage, so from an early date the warming of the cockles is often physiological and not merely metaphorical.

Also intriguing is this excerpt from Marin La Voye, Eugénie, the Young Laundress of the Bastille (1851):

No sooner had you been unlucky enough to utter a word before her [Madame Bonamie], that tended in the least to establish a positive distinction of rank, in what we term the population of a country, whereby you fixed, as it were, the proper place of every individual, according to his birth, fortune, or talent, the offended laundress felt the cockles of her heart, good at all other times, begin to close, and a strange optical delusion instantly fell before her eyes, through which she fancied you looked like a a suddenly declared foe.

Is La Voye describing ventricle fibers compressing or internal passageways of the heart narrowing or both?

A firm and convincing conclusion about the original identity of "the cockles of the heart" is possible at this remove from the term's origin may be beyond our reach. One particularly tantalizing early instance of cockles is from the 1608 translation of Du Bartas referring to Jezebel's effort "To curl the cockles of her new bought head," where the cockles may be ringlets or crimps. Similarly ambiguous is Shakespeare's reference to "cockled snails" in [Love's Labour's Lost], where cockled may mean "turbinated" or simply "shelled."

In any case, it seems to me that interpreting "the cockles of the heart" as being suggested by the similarity between the shape of the bivalve cockle and a human heart (or the Valentine's Day representation of a human heart has a serious drawback—namely, that the expression is plural and subordinate to the heart ("the cockles of the heart"), not singular and equivalent to it ("the cockle that is one's heart," say).

To my mind, the most promising candidates for original meaning of "the cockles of [one's] heart" are (1) the ventricle fibers known to early anatomists as cochleae cordis, or (2) the hidden recesses of the heart, conceived of as chambers connected by a winding passageway. The crucial (and I think unanswerable) question is whether the first conception of "the cockles of the heart" was of a collection of ridges or striations (cochlea as "shell-fish," in Kersey's definition) on the outside of the heart or as a collection of hidden chambers or recesses joined by a winding passageway (cochlea as "sea-snail," in Kersey's definition) in the heart's mysterious interior.