I've been messing around in Universe Sandbox for a while and noticed that as a planet heats up, it glows like a blackbody starting at ~4000 K. Is the simulation here accurate, or do very hot planets glow differently based on their composition?

1 Answers

At high temperatures, do planets glow like blackbodies?

Yes, and at low temperatures too!1

1As @DavidHammen points out, since there's likely going to be a star nearby the planet, it will also be reflecting light from it, so the "glowing" with thermal radiation may in some cases be masked or at least mixed with reflected thermal radiation from the star.

But as far as I know, when thermal infrared telescopes spot asteroids, they are seeing the asteroid's own thermal "glowing", not reflected thermal IR from the Sun.

To address this more fully I've just asked When thermal infrared space telescopes spot asteroids, are they seeing the body's own thermal emission, or reflected TIR from the Sun?

This is a really interesting interdisciplinary question and as this is too long for a comment I'll write something here.

A black body is an idealized concept. It's too long to quote in full but at a temperature $T$ its emission spectrum is given by Planck's law:

$$B(\nu, T) = \frac{2 h \nu^3}{c^2} \frac{1}{\exp \left(\frac{h \nu}{k_B T} \right) - 1}$$

or

$$B(\lambda, T) = \frac{2 h c^2}{\lambda^5} \frac{1}{\exp\left(\frac{h c}{\lambda k_B T}\right) - 1}$$

where $h$, $c$ and $k_B$ are the Planck constant, the speed of light and the Boltzmann constant.

Their peaks are at slightly different colors because they are differentials (i.e. per unit frequency vs per unit wavelength).

Now we are familiar with the Stefan–Boltzmann law where the total power radiated by an object of area $A$ integrated over all colors is

$$P = A \varepsilon \sigma T^4$$

where $\sigma$ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant and $\varepsilon$ is the emissivity of the surface.

If you wanted to know the thermal emission spectrum of a body you'd multiply the Planck distribution $B$ of an idealized black body by the object's emissivity $\varepsilon$.

But wavelength-dependent emissivity is what you're really after

The primary way that a hot planet will deviate from a Planck distribution is in $\varepsilon$ and especially its variation with wavelength (which they often forget to tell you about in class); $\varepsilon(\nu)$ or $\varepsilon(\lambda)$.

Extreme example of wavelength-dependent emissivity

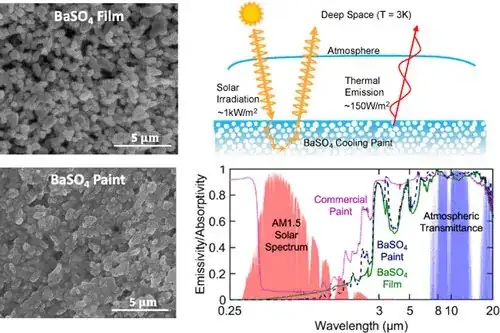

There was a recent announcement of a special "ultrawhite" paint which had extremely high albedo (97.6%, and therefore low emissivity) in the visible and a very low albedo (high emissivity; ~96%) in the "sky window" of thermal infrared.

If you painted this on something, it could potentially cool itself even in daytime by radiating heat into the "cold of space" through the sky window wavelength range where our atmosphere is somewhat transparent to thermal IR.

Source ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces @ACS_AMI tweet

Slightly related trivia

In the case of asteroids and dwarf planets (things with solid surfaces and no optically appreciable atmosphere) and especially for those too small to resolve their size, we often assume their visible albedo is low, something like 0.1 if we have no other information.

Their emissivity in thermal infrared is often assumed to be of order 0.9-ish, and that's important since space telescopes that hunt for NEOs (some up there already and ones that haven't yet got off the ground) use thermal IR to spot NEOs against a cold CMB background.

But the wavelength-dependent emissivity will show up as a deviation from a Planck distribution, and that can offer some clues as to composition (e.g. much tholins vs not so much tholins)

Why the thermal imaging of Mercury's surface requires a telescope on a jet flying through an eclipse? describes an example of using the surface brightness of an object falling within a wide band of thermal infrared wavelengths to determine its temperature. What they are doing is assuming some constant emissivity or, being NASA, maybe they factored in a previously wavelength-dependent emissivity from spectroscopy during analysis; the camera itself probably doesn't have spectral capabilities.

If you buy an infrared thermometer it either has a pre-programmed constant emissivity of like 0.9 or 0.95 or it lets you change it. The ones they stick in your ear or at your forehead are preprogrammed.

- 1,213

- 2

- 12

- 27

- 31,151

- 9

- 89

- 293

-

1The added example of the paint makes the dependence of Planck's law on wavelength (or frequency) even more clear. It goes to show that paint and astronomy go together very well! Very good answer too! – Deschele Schilder Jun 19 '21 at 06:08

-

1@Methadont That's good to hear, thanks! Paint and astronomical bodies at least (in decreasing order of relevance): Why paint only one-half of Bennu? and Do you recognize these space artists who made this (possibly) first “paint-by-numbers” image of Mars? and Could an ISS astronaut photograph something like this 1km “Van Gogh” if they knew it was there? – uhoh Jun 19 '21 at 06:12

-

1Especially the Bennu question is a nice one! I never thought about painting a dangerous asteroid. To nuke them was the only way, I thought. But paint can do the job... – Deschele Schilder Jun 19 '21 at 06:21

-

1But with the absorption bands they *don't* glow like blackbodies(?). Perhaps qualify the "yes"? – Peter Mortensen Jun 19 '21 at 12:52

-

@PeterMortensen It's like the absorption spectrum of the sun. As a whole, it's pretty black body-like. But there are certain wavelengths emitting somewhat less. When the sun eclipses the "negative" of the spectrum will appear (emerging from the sun's gaseous layer). For a planet, there is no gaseous layer but there will be absorption for certain wavelengths. So not completely black body, but almost. – Deschele Schilder Jun 19 '21 at 14:46

-

@PeterMortensen ya the scope of my answer is probably does not encompass the effects of the atmosphere, and since the question does ask about planets as hot as 4000 K it opens up the question of what that even means; this chart lists 17 elements (starting with rhodium) with boiling points above 4000 K, mostly metals except for carbon. I think that should be addressed somehow but I'm not sure I'm qualified to state with certainty the nature of a planet that's been heated to such a temperature! – uhoh Jun 19 '21 at 21:17

-

@Methadont ditto. – uhoh Jun 19 '21 at 21:17

-

I somewhat disagree with "Yes, and at low temperatures too!" Blackbody radiation is unimodal. The electromagnetic radiation from planets has a markedly bimodal distribution. The higher frequency component in that bimodal distribution is reflected sunlight (which is not quite blackbody). The lower frequency component in that bimodal distribution is thermal radiation, and if the planet has an atmosphere, that too does not quite follow a blackbody distribution. – David Hammen Jun 20 '21 at 16:45

-

@DavidHammen that's a really good point to point out. Note that "Yes, and at low temperatures too!" is a direct response to the sentence "At high temperatures, do planets glow like blackbodies?" and one can't argue that they don't at low temperature. As far as I know (and please feel free to correct me if I'm wrong) there's nothing about glowing that prevents simultaneous reflecting. I think it's correct as written, but perhaps incomplete. But that's consistent with "somewhat disagreement". I've posted an extended caveat to it for completeness and will ask a new question presently. – uhoh Jun 20 '21 at 23:44