Following a previously asked questions on prediction intervals for a logistic regression classifier, I'm currently experiencing a conundrum.

I want to test a procedure to reverse-engineer the alteration of the spatial coordinates of my plot data. For each plot in my dataset, the procedure generates a series of potential coordinates, which could or couldn't contain the real coordinates.

After this procedure I have two datasets: the real plot data/coordinates with, let's say, 2k observations (let's call it tr_data), and the one with estimated coordinates, est_data, where for each plot.ID in the tr_data there are 1 or multiple entries (let's say 20k observations total).

To keep things simple, I trained a Random Forest Classifier on the two datasets. The problem is a multiclass problem, with 7 classes and an imbalanced dataset. I'm trying to predict probabilities, not 0-1. I validate my models on an independent dataset of 500 observations. I'm not doing any feature selection/hyperparameter tuning.

OA of the model trained on tr_data is 0.72

OA of the model trained on est_data is 0.45

(I know there are better metrics than OA for probabilities, like logloss, but bear with me)

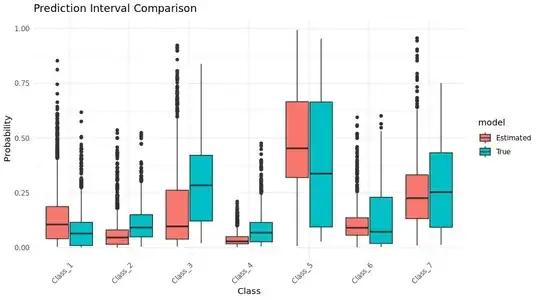

I could stop here, but to make the comparison more robust I'd like to compare prediction intervals (PI) and probability coverage. I expect for example to have wider PI for the model trained on est_data compared to the other one.

I created 100 bootstrapped samples for both training datasets, trained models and generated the 95% PI for each class from the validation set. See plot.

Thing is that for more than one class and for both types of datasets (tr and est) the lower bound of the PI ends up being 0, while the upper bound in some cases is as high as 0.95. Nothing wrong for PIs, but for probability coverage this means that more than 95% of my observations actually fall in the 95% PI. My questions then are:

- Am I computing the 95% PIs correctly? They seem insanely wide.

- Does it make sense to compute prediction interval coverage probability (PICP) in this case? I ended up with <1% of observations outside of the 95% PI.