Short Answer: BCD rules over a single byte integer.

The claim that programs stored dates as two ASCII or similar characters because computers were limited in resources seems wrong to me

The point wasn't about using ASCII or 'similar', using only two decimal digits. That can be two characters (not necessary ASCII) or two BCD digits in a single byte.

because it takes more memory than one 8-bit integer would.

Two BCD digits fit quite nicely in 8 bits - in fact, that's the very reason a byte is made of 8 bit.

Also in certain cases it's also slower.

Not really. In fact, on quite some machines using a single byte integer will be considerable slower than using a word - or as well BCD.

In addition to perform arithmetic on the years the software would need to convert the two characters back to an integer whereas if it were stored as an integer it could be loaded without conversion.

That is only true and needed if the CPU in question can not handle BCD native.

This is where the slower in certain cases comes in. In addition it could make sorting by year slower.

Why? Sorting is done usually not by year, but as a full date - which in BCD is 3 Byte.

In my view the only reason I can think of for why someone would store a year as two characters is bad programming

Are you intend to say everyone during the first 40 years of IT, up to the year 2000 were idiots?

or using a text based storage format

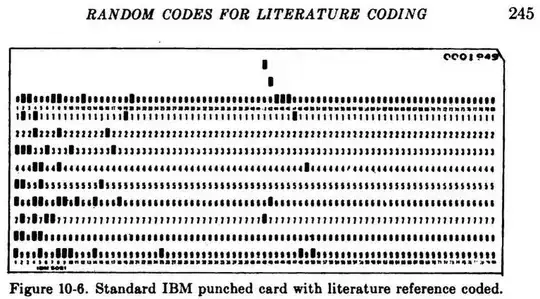

Now you're coming close. Ever wondered why your terminal emulation defaults to 80 characters? Exactly, it's the size of a punch card. And punch cards don't store bytes or binary information but characters. One column one digit. Storage evolved from there.

And storage on mainframes was always a rare resource - or how much room do you think one can give to data when the job is to

- handle 20k transactions per hour

on a machine with a

- 0.9 MIPS CPU,

- 1.5 megabyte of RAM, some

- 2 GiB of disk storage?

That was all present to

- serve 300-500 concurrent users

Yes, that is what a mainframe in 1980 was.

Load always outgrew increased capabilities. And believe me, shaving off a byte from every date to use only YYMMDD instead of YYYYMMDD was a considerable (25%) gain.

(such as something like XML or JSON which I know those are more contemporary in comparison to programs that had the Y2K bug).

Noone would have ever thought of such bloaty formats back then.

Arguably you can say that choosing a text-based storage format is an example of bad programming because it's not a good choice for a very resource limited computer.

Been there, done that, and it is. Storing a date in BCD results in overall higher performance.

- optimal storage (3 byte per date)

- No constant conversion from and to binary needed

- Conversion to readable (mostly EBCDIC, not ASCII) is a single machine instruction.

- Calculations can be done without converting and filling by using BCD instructions.

How many programs stored years as two characters and why?

A vast majority of mainframe programs did. Programs that are part of incredibly huge applications in worldwide networks. Chances are close to 100% that any financial transaction you do today still is done at some point by a /370ish mainframe. And these are as well the ones that not only come from punch card age and tight memory situations, but also handle BCD as native data types.

And another story from Grandpa's vault:

For one rather large mainframe application we solved the Y2K problem without extending records, but by extending the BCD range. So the next year after 99 (for 1999 became A0 (or 2000). This worked as the decade is the topmost digit. Of course, all I/O functions had to be adjusted, but that was a lesser job. Changing data storage formats would have been a gigantic task with endless chances of bugs. Also, any date conversion would have meant to stop the live system maybe for days (there were billions of records to convert) -- something not possible for a mission critical system that needs to run 24/7.

We also added a virtual conversation layer, but that did only kick in for a small number of data records for a short time during roll over.

In the end we still had to stop short before midnight MEZ and restart a minute later, as management decided that this would be a good measure to avoid roll over problems. Well, their decision. And as usual a completely useless one, as the system did run multiple time zones (almost around the world, Wladiwostock to French Guiana), so it passed multiple roll over points that night.