A simple upper bound is $\sqrt{2} + 2\times 2\pi + 2 \approx 15.98$ miles.

If we travel on two circles of radius $1$, parallel to each other and $2$ miles apart, and whose centers are collinear with the starting point, we can guarantee to hit the space station. To do this, we travel $\sqrt{2}$ miles to the circumference of the first circle, travel around it, then travel the $2$ miles to the other circle and travel around that.

As @MPeti mentioned in the comments below, we can improve this by using the optimal path in the 2-d version instead of circles. The length of the path now becomes $\sqrt{2+\frac{1}{3}} + 2\times(\frac{7\pi}{6}+1+\sqrt{\frac{4}{3}-1}) + 2 \approx 14.01$ miles.

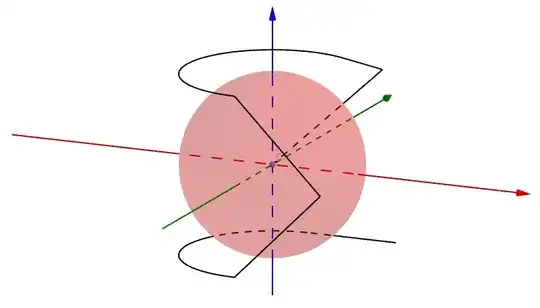

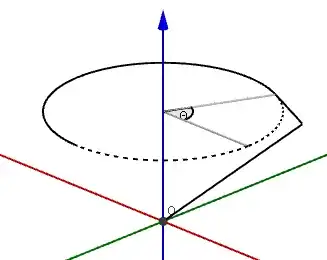

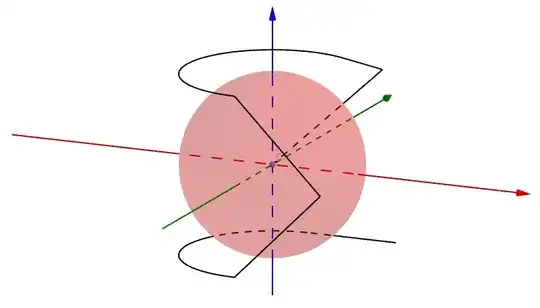

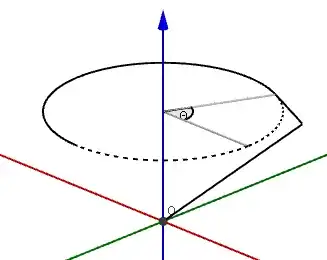

If we don't travel the last mile in the 2-d path and travel between the two paths in a triangular fashion, and realise that the optimum path in 2-d is not necessarily the optimum path in 3-d, we can reduce the length further to approximately $12.74$ miles.

A graphic to help visualisation (made using GeoGebra):

The length of the top path + the initial radial path is $\frac{3\pi}{2}-\theta+\tan{\frac{\theta}{2}}+\sqrt{\sec^2{\frac{\theta}{2}}+1}$, which according to Wolfram Alpha is minimised when $\theta \approx 1.14372$ with a length of $l_1 \approx 5.76604$ miles.

The length of the bottom path is $\frac{3\pi}{2}-\theta+\tan{\frac{\theta}{2}}$, which is minimised when $\theta = \frac{\pi}{2}$ with a length of $l_2 = \pi + 1 \approx 4.14159$ miles.

Adding these two lengths and the length of the semicircular path between them, we arrive at a total length of $l_1 + 2\sqrt{2} + l_2 \approx 12.74$ miles.