The correct proof

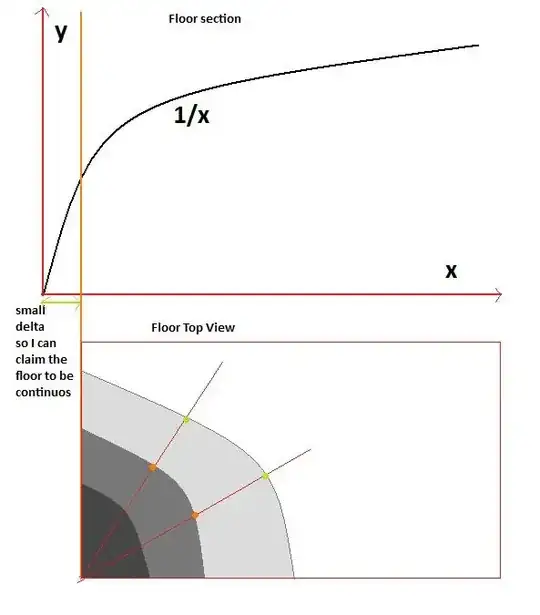

First we assume that the floor has elevation that is a continuous function of the position bounded between zero and the $p$ where $p$ is some parameter that depends on the shape of the table (see below for details), and that the table legs are lines that end in the points of a square $ABCD$. The problem is then assumed to be to position the table so that all four legs touch (and do not go through) the floor.

In the following method note that every step is physically possible in the sense that the table never intersects the floor.

First note that there is a rotational orientation of the table (based on $p$), such that for any point on the floor we can hold the table in that orientation such that one leg touches the floor at that point. This is possible because we can hold the table sufficiently tilted and above the floor, so that the end of the lowest leg is directly above the desired point, and now lowering the table results in that leg touching the floor first by the intermediate value theorem (IVT) and the tilt. We can assume that $A$ is the end of that leg touching the floor at the chosen point. Now tilt the table around the line through $A$ that is perpendicular to $AB$ and horizontal, such that $B$ goes towards the floor, until the leg ending at $B$ touches the floor by IVT. Tilt the table around the line through $AB$ until a third leg touches the floor by IVT. Note that if the third leg is not there we can tilt some more so that the last leg touches the floor by IVT.

Note that in the above subroutine it is easy to choose the initial orientation of the table such that rotating the table by any angle around the vertical will give yet another initial orientation that works. So we get a function with its inputs being the desired point and the initial rotation around the vertical and its output being a table 'position' with $ABC$ on the floor (and $D$ possibly below). It is not hard to prove that this function is continuous, given some weak conditions on the floor (see below). This is the key.

Perform this subroutine once to get $ABC$ on the floor. To be precise we simply get any three legs on the floor, and then rotate the table such that those legs are the ones that actually have endpoints being $ABC$. Then choose any path $P$ from $A$ to $B$ on the floor. Drag the table on the floor such that $A$ follows $P$. We claim that we can do so with $B,C$ remaining on the floor. This follows from the subroutine's continuity since we can keep the rotation around vertical fixed and just use the subroutine on the points along the path. In fact this is what can actually happen physically if you constrain the table's movements. Now drag the table on the floor such that $A$ remains where it is while $B$ goes to where $C$ originally was. Again we claim that we can keep $B,C$ on the floor in the process of dragging. This is because the subroutine applied to all possible rotations around the vertical gives all possible table 'positions' where $A$ is in that place and $B,C$ are on the floor. In particular, a quarter turn around the vertical gives a table 'position' where $A,B$ are at the original locations of $B,C$, and in that case $D$ is below the floor. By IVT, there is a smallest rotation less than that quarter turn such that the subroutine will give a table 'position' with $D$ exactly on the floor. This means that we can drag the table to move $B$ 'around' $A$ keeping $B,C$ on the floor because of the subroutine's continuity, and before a quarter 'turn' we would have found the solution.

Table parameter

Clearly if the table top is much wider than the distance between legs, the method can fail to work simply because the side of the table top hits the floor. In the worst case the legs are so short and the table top has some downward protrusions that reach the plane through the square! In that case certain floors would make the problem impossible. However, as long as there is a plane that completely separates the leg ends from the table top, there will be some suitable parameter $p > 0$ for the above method to work.

Similarly if the legs point outwards, the middle part of the legs may hit the floor if we use the method. Again, for reasonable tables there is some suitable parameter $p$ that works. (No I'm not going to rigorously prove this.)

Floor conditions

Also, to ensure that the subroutine works, any sphere with centre on the floor and radius $AB$ must intersect the floor at points that are at unique angles from the centre. I'm not sure whether this condition can be removed without making the solution non-constructive, in the sense that we can easily prove existence of a solution but there may not be a physical method (like the one above) to obtain it systematically from any random starting position.

In any case, this condition is fulfilled by various simpler conditions such as having Lipschitz constant at most $1$.

No lateral-thinking, I was going to start with no because "The floor is lava", followed by Rubber, Gravel, Grating, Water or a Whale. – Dorus Aug 27 '15 at 12:53