Opinions are divided on this. It's because no dictator has quit because his own car was out of gas or out of spare parts. So one can easily claim that sanction don't work (like that). The discussion on indirect effects easily gets complicated by confounders, but at least some academic research finds an effect, mind you, more so in the case of democracies or at least "mixed regimes" (e.g like Milosevic in Serbia) than for the most autocratic regimes.

This study (by Marinov) I know of was published in 2005, so it misses a lot of the more recent instability in the Arab world etc. (Somewhat ironically, it finds Libya to be one of the most stable countries [barely behind China], although that data point claim [Libya] surely look silly with two additional decades of observations added. So there's that kind of caveat emptor with this kind of research.) Anyhow, the main points of the paper are roughly:

The benchmark for measuring success is typically

whether economic sanctions can change the behavior of a

foreign government at an acceptable cost. The most comprehensive study of the effectiveness of economic sanctions assesses that the measure works about 35% of the

time (Hufbauer, Shott, and Elliott 1990).

Critics respond that the success rate has been overstated (Pape 1997). [...] Many explanations can be offered for why the

controversy endures. One issue lies with the measurement

of “success.” What is success and how is it measured is often contested even by the very participants in an episode.

Another issue is whether success should be attributed to

sanctions. Economic pressure typically takes place alongside other important events and developments, such as a

weak economy or a foreign military intervention. Assigning the relative merits of economic coercion in each case

can cause reasonable people to disagree (Elliott 1998). [...]

I take an approach analogous to that in the literature on the

relationship between government instability and a country’s level of wealth [...].The main dependent variable is leadership change. I ask

whether the presence of sanctions against a state’s leadership in a given year makes it more likely for the leader to be replaced.

I include in the test all countries with population over

500,000 (N = 160), and the period 1947 to 1999.

I break down the data

into country-year observations: a country gives rise to

one observation for each calendar year. This makes for a

total of 6,782 observations in the full data-set. [...]

The estimation procedure I use is logistic regression

with fixed effects. [...] The reason interaction terms between Democracy,

Mixed Regime, and the natural log of years in office ln(t)

are included is to allow for the effect of political institutions to vary over time. As suggested by Chiozza and

Goemans (2004b) and others, we can expect to find varying effects of institutions over time. Because the effect of

autocracy is folded in the (nonlinear) baseline hazard, no

separate dummy is included.

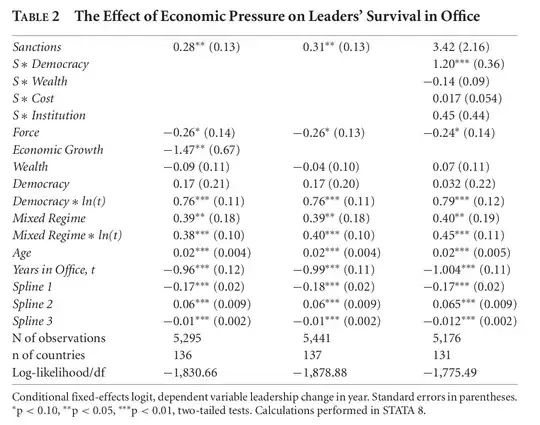

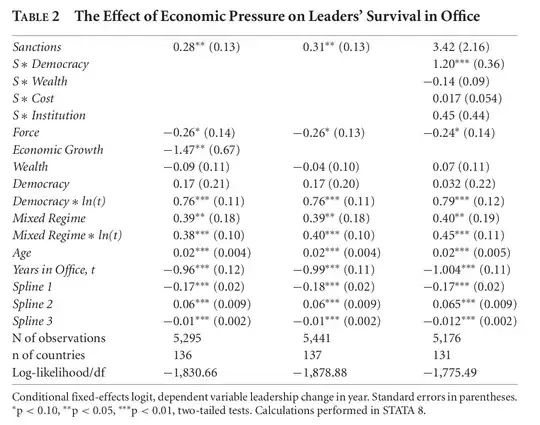

Economic sanctions are significant as expected. A leader who is subject

to economic sanctions in a given year is, on average, more

likely to lose office in the following year. The result holds

while adjusting for country-specific government instability and for a range of other factors, including the use of force.

All other variables, except for the use of force perhaps,

are signed as expected. Lower economic growth hurts the

political survival of leaders in office. The effect is strong

and statistically significant. This finding is consistent with

what we know about government instability in good and

bad economic times.

Perhaps surprisingly, the use of force strengthens a

leader’s hold on office. The use of force likely generates

two types of effects. One, it may weaken a leader. Second,

it may generate a “rally around the flag” effect. The finding

here indicates that what predominates, or what these two

effects average out to, is that a leader is less likely to lose

power.

Averaged out over all 136 countries, the risk of losing

office, when sanctions are not in place, is 0.146. When

pressure is present, the hazard rises to 0.183. This means

that sanctions cause a 28% average increase in the risk of

losing power. This is, clearly, more than trivial trouble for

incumbents.

The theoretical argument stated that one way pressure destabilizes is by lowering economic growth. If this is

the case, growth and sanctions are not independent. This

suggests that part of the effect of sanctions is currently being picked by economic growth. Dropping growth should

strengthen the effect of sanctions. Column 2 on Table 2

shows that this is the case. When economic growth is

dropped from the model, the coefficient of sanctions increases from 0.28 to 0.31. The significance level also improves, in line with expectations.

(I'm not going to explain all the variables in the table here. Read the paper for that. The spline coefficients at the end allow for the effect of the duration of the government to [nonlinearly] vary both ways, because there are theoretical disputes whether a leader/regime gets stronger or not after coming in office.)

So, although those imposing sanction won't so readily admit it,

making ordinary people suffer via sanctions... is part of the solution they provide in pressuring at least leadership change if not regime change.

There's also the catch that absent the threat of (any) sanctions we might see more "bad behavior" from some governments, but this hard to ascertain because of unobservables.

The

problem is, target governments are more likely to have

private information on their prospects for surviving in

office under pressure. Such information will not be measurable. The selection effect will remain undetected. And

it will bias estimates of the impact of sanctions downward.

The more prevalent this problem is, the more biased statistical estimates will be.

A newer paper Escribà-Folch & Wright (2010) that I haven't read beyond its abstract has tried to further distinguish between types of

authoritarian regimes. It finds

Using data on sanction episodes

and authoritarian regimes from 1960 to 1997 and selection-corrected

survival models, we test whether sanctions destabilize authoritarian rulers

in different types of regimes. We find that personalist dictators are more

vulnerable to foreign pressure than other types of dictators. We also

analyze the modes of authoritarian leader exit and find that sanctions

increase the likelihood of a regular and an irregular change of ruler, such

as a coup, in personalist regimes. In single-party and military regimes,

however, sanctions have little effect on leadership stability.

I haven't delved into the paper (it's open access though, so you can DIY that), but given the time range, it's possible a lot

of that is explained by the single-party regimes being mostly in a block during the

cold war. What these studies generally don't seem to model well is whether the

sanctioned country also/still has allies that "prop it up" in some way, including

threatening [military] counter-intervention in case of regime change (which was definitely

the case during the cold war).

Somewhat aside: a 3rd paper Wood (2008) finds that sanctions also tend to increase internal

repression in the target at least in the short run (and this is correlated with the

severity and extent of the sanctions too, as proxied by their effect on GDP, so e.g.

UN sanctions increase repression more than just US ones do.) So one could say that merely

alleviating internal human rights abuses in the short term is not really helped by (broad) economic

sanctions.

The results of Marinov (recall they are for pre-2000 data) have been somewhat reproduced by Soest & Wahman (2014) using a newer dataset covering 1990-2010, and which additionally is more discerning of the type of sanction imposed and its stated goal(s). So, e.g. sanctions that nominally request compliance with some WMD demand aren't put in the same bin as those that demand multi-party elections, for instance. Likewise they look at more outcomes than mere leader change, e.g. a change in democratic index value ("a combined Freedom House and Polity IV score"). This is a fairly long paper (more than twice the number pages compared to Marinov's) so I'm not going to be able to capture its findings here except in part, but towards the end they have models fairly similar to Marinov's. I'm quoting this mostly for the concrete examples they illustrate their findings with (after the table).

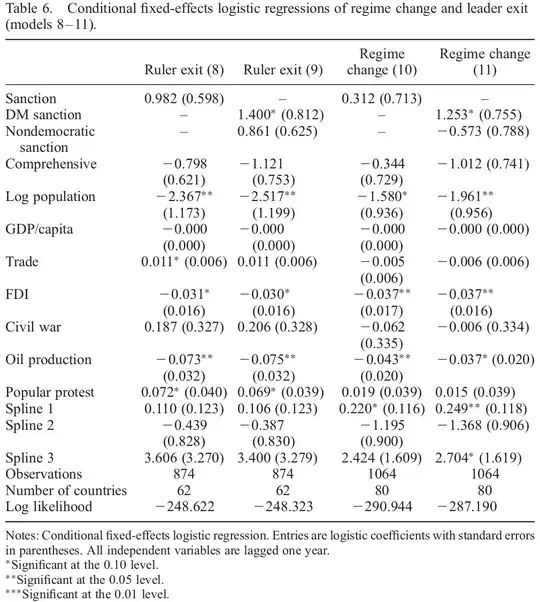

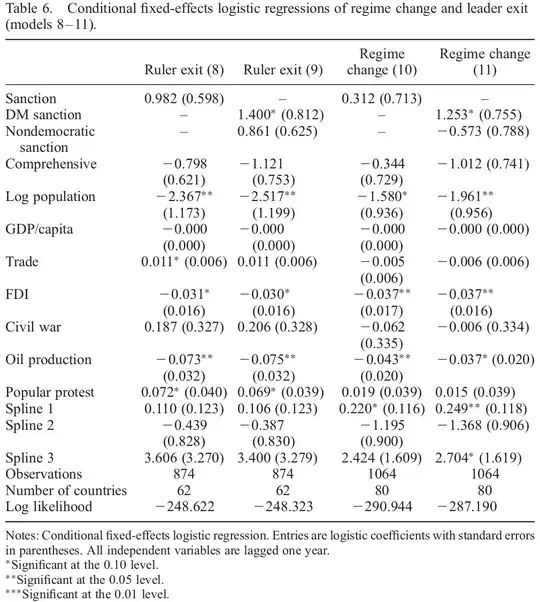

Model 8 shows no general

relationship between sanctions and a higher probability of ruler exit. However,

looking at only democratic sanctions in Model 9, we see a significant positive

relationship. Our findings reaffirm Marinov’s conclusion that sanctions generally

increase the probability of leadership exit. Looking at the models for regime

change, we once again see no significant effect of sanctions generally (Model

10), but we find a significant effect for imposed democratic sanctions (Model 11).

A brief glimpse at some sanction cases reveals that different mechanisms may

account for increased democracy levels in targeted authoritarian regimes, with the

two major ones being (1) elite splits (and, in turn, regime changes and leadership

exit) and (2) democratic concessions without regime and/or leader change. In

Guatemala (1993), for instance, the military ousted President Serrano – who had

unconstitutionally dissolved parliament and the judiciary – after the US and its

allies imposed sanctions. An interim president took over, and the country’s democratic institutions were restored. In Nicaragua (1996) and Thailand (1993), sanctions similarly contributed to regime change. However, democratic sanctions

rarely create liberal democracies instantly; rather, they lead to multiparty autocracies. In addition, democratic sanctions have different effects on autocratic rulers

and regimes. In Peru, sanctions contributed to democratization without ruler

change. When President Fujimori suspended the legislature and introduced rule

by decree in 1992, the US withheld military assistance and economic aid and

blocked Peru’s efforts to obtain loans from international financial institutions. In response, Fujimori agreed to hold elections and to reinstate formally democratic institutions. Although his presidential dominance persisted until 2000,

Peru’s political system was liberalized to some extent for the remainder of his

time in office. In this particular case we could, hence, observe both institutional

change and democratization, without change in leadership.

Interestingly, Table 6 also shows that FDI decreases the chances of both ruler exit (Models 8 and 9) and regime change (Models 10 and 11). However, this might be due to international investors’ aversion to investing in politically

unstable countries in the first place. Regarding sanctions, it is interesting to see

that comprehensive sanctions decrease the likelihood of regime change in

Models 9 and 11. We also see that (1) larger countries are more stable in terms

of both leadership exit and institutions and (2), as expected, that richer countries

experience fewer regime changes (Models 10 and 11). Reaffirming the idea of the

resource curse, we also see more regime stability in regimes with larger oil production (Models 8 – 11).

There are several instances where regime change has been preceded by sanctions, although we would not argue that the relationship between sanctions and

institutional change was causal in all these instances. [...] Changes in regime type rarely lead to full democracy, and countries sometimes transition from what could generally be perceived as

a more democratic regime type to a less democratic one. However, most of the

instances where change in regime type is preceded by democratic sanctions

show signs of at least limited liberalization (such as the implementation of multiparty elections).

Another (sizeable) part of their paper--meaning the models <8 are linear ones, in the style

of Peksen and Drury (2010) (also Peksen 2009), but unlike those papers (which use pre-2000 data) Soest & Wahman find that if one accounts for the declared goal of the sanction, those specifically aimed at obtaining some democratic improvement have been successful at least in the sense of achieving statistical significance

... although that mere threats of sanctions have been much less so; in particular mere threats of sanctions to obtain democratic concessions are significantly less successful than those aimed at obtaining other kinds of concessions.

Our analysis using the TIES [it's a sanctions database] data demonstrates that democratic and human rights sanction threats are rarely effective. Only 10% of sanctions related to democracy or human rights accomplished complete or partial concession by the target country at the threat stage. The corresponding number for sanctions with other goals is more than double (22%). Moreover, sanction senders are generally serious about their democratic sanctions. Where targets did not comply, 85% of all democratic sanction threats were carried out, compared to 79% for the rest.