It would be nice if we distinguished between "polar coordinates" and "polar parameterizations".

Let $\Omega \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ be an open set which does not contain any loop around the origin. Then a choice of polar coordinates for $\Omega$ is a choice of smooth section of $P$. Such a section always exists and, if $\Omega$ is connected, the section is completely determined up to a sign of $r$ and a multiple of $2\pi$ for $\theta$. You are correct that we never have polar coordinates where $r$ changes sign.

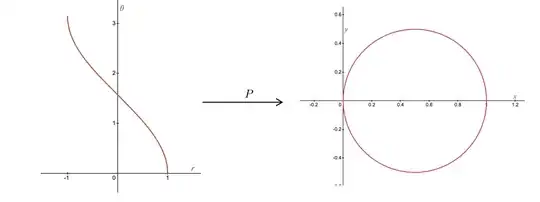

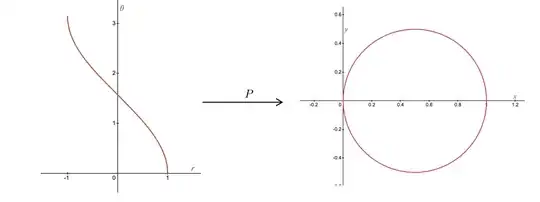

On the other hand, we can describe some subsets $S_{x,y} \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ conveniently using polar parameterizations. A polar parameterization is just describing $S_{x,y}$ as $S_{x,y} = P(S_{r,\theta})$ for some $S_{r,\theta} \subset \mathbb{R}^2$. Note that polar coordinates are polar parameterizations, but not all polar parameterizations are polar coordinates!

When we write "polar equations" are are actually talking about polar parameterizations, not polar coordinates. Let's look at the equation $r = \cos(\theta)$, with $\theta \in [0,\pi]$ to describe a circle.

Note that the restriction of $P$ from the graph of $r = \cos(\theta)$, with $\theta \in [0,\pi]$, is smooth through $r=0$! This is as nice as it gets.

In general if $f: (\theta_1, \theta_2) \to \mathbb{R}$ is any smooth function, the map $\theta \mapsto (f(\theta),\theta) \mapsto P(f(\theta),\theta)$ will also be smooth. When we write $r = f(\theta)$ for $\theta \in (\theta_1, \theta_2)$ we are actually thinking about a parameterized curve in the $(x,y)$ plane. We are not (as you claim in the OP) graphing the equation $r = f(\theta)$ where $(r,\theta)$ are polar coordinates for some region containing the circle (in fact, no such polar coordinates exist since no region containing the origin has a smooth section).

Usually you will not want to include a point where $r = 0$ even in a parameterization of a 2D region, since $P$ is locally "two to one" on any punctured neighborhood of a point $(0,\theta_0)$.

However, there are even circumstances when this is natural. When I want to find the area of the disk bounded by $r = \cos(\theta)$, it is natural to use an integral from $\theta = 0$ to $\theta = \pi$.

It is still one to one and nice enough that you can write the whole area of the disk as

$$

\int_0^\pi \cos^2(\theta)\textrm{ d}\theta

$$

with no issue (breaking it up from $0$ to $\frac{\pi}{2}$ and $\frac{\pi}{2}$ to $\pi$ gives two nice non-overlapping pieces).

I wouldn't usually think about the pre-image when I write down this integral: I just think about cutting the disk into small pieces.

While I agree that for many purposes it is nice to restrict to $r>0$ it is not always needed.

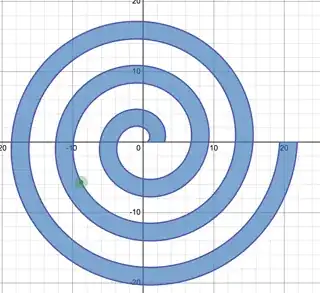

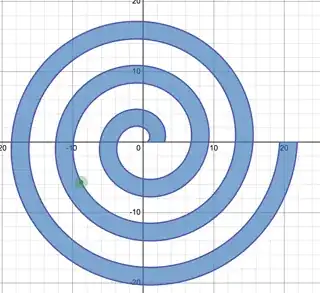

I want to illustrate how a region can have polar coordinates without restricting $\theta \in [0,2\pi)$. For example, $P$ restricts to a diffeomorphism between the rectangle $(0.5,3) \times (0,6\pi)$ in the $(r,\theta)$ plane and the region $ 0.5 + \theta < r < 3 + \theta$ with $\theta \in (0,6\pi)$. I would like to be able to work with this region without breaking it up into chunks which are artificially restricted to only go from $\theta = 0$ to $\theta = 2\pi$.

I will also note that contending with these kinds of issues is bread and butter stuff in complex analysis.

EDIT: One more note. The OP says that:

This aligns well with the view that coordinates are functions on the manifold, or, if you wish, that they are numbers assigned to physical points. Then, equations in polar coordinates, such as $r^2 = \sin(\theta)$, simply describe the set of points which satisfy the equation when fed into it (with some choice of a branch for $\theta$

), just as it is the case with equations in Cartesian coordinates.

This point of view has a few serious drawbacks.

First of all $\theta$ is not a coordinate map. It is locally but not globally. Hence the need for a choice of the branch.

More seriously, this interpretation of a "polar equation" never admits $r=0$ as a solution. Let's be explicit and attempt to define

$$r(x,y) = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}$$

$$

\theta(x,y) = \operatorname{atan2}(x,y)

$$

See this definition of $\operatorname{atan2}(x,y)$.

Then according to OP definition a solution of $r^2 = \sin(\theta)$ is a point $(x,y)$ satisfying

$$

x^2 + y^2 = \sin(\operatorname{atan2}(x,y))

$$

Since $\operatorname{atan2}(0,0)$ we must admit that $(0,0)$ is not a solution of $r^2 = \sin(\theta)$ under the definition of the OP.

This is not to say that this is a poor definition: it is good for some purposes and not for others.