I gave a similar post to this one touching on this on Math.StackExchange.

Basically, the way I would go about it is to say that there is a very easy way by which one can think of at least Riemann integration (the usual definition given in a "most courses" calculus course) as an inverse of differentiation by construction: that is, the relationship between the two is not an "accident", but design, so that given one, you could fairly easily be led to the other.

And to do that, I'd first suggest getting rid of the whole "slope" vs "area" business altogether - if anything, those are best given as theorems to be proved, after you have other, free-standing definitions of a tangent line and an area which, by the way, can be done, but just too-often aren't, in favor of various hand-waving arguments.

Instead, the relevant idea is change: the derivative of a function $f$, i.e. $f'$, stands for a kind of "sensitivity" measure. Suppose that $f$ were like a kind of meter or instrument, with a knob attached to it, and a readout of some kind. The knob attached is the function's input argument, typically denoted $x$. The indicator on the readout is the return value, $f(x)$. If $x$ is set at some value of interest $x_0$, then likewise the readout will be at $f(x_0)$. Now suppose you "wiggle" the knob $x$ back and forth a little bit, and you see how the needle $f(x)$ responds to that small impulse. For a continuous function, the size of the output's wiggle will be smaller in absolute terms the smaller you make the input, but the proportionate size, i.e. how much it wiggles relative to how much you wiggle the input value, may not be. When we say $f$ is differentiable, what that means is that there exists at each point $x_0$ a proportionality factor $f'(x_0)$ such that

$$f(x \pm \underbrace{dx}_\mbox{"wiggle" in $x$}) \approx f(x_0) \pm \underbrace{[f'(x_0)\ dx]}_\mbox{"wiggle" in $f(x)$}$$

so that

$$\mbox{proportional "wiggle"} = \frac{\mbox{"wiggle" in $f(x)$}}{\mbox{"wiggle" in $x$}}$$

so long as the change $dx$ is suitably small

Integration, then, goes the other way. Suppose that I am given now, not the function $f$, but only its derivative, $f'$, and want to find $f$. First off, one should observe that since $f'$ only deals with changes in the input, to start, we actually need one more piece of information, and that is some sort of initial value, i.e. $f(0)$. Suppose this to be given as well.

Starting at $f(0)$, suppose we apply a small, but nonzero, change $\Delta x$ to the input, i.e. we ask, "given $f(0)$, what is $f(0 + \Delta x)$, to the best we can do?" Well, since we know $f(0)$ and $f'$, then since $\Delta x$ is a small change or "wiggle", we can say that approximately,

$$f(0 + \Delta x) \approx f(0) + [f'(0)\ \Delta x]$$

which is just what you see above.

Now, suppose we take another step of $\Delta x$. We're now going from $x = 0 + \Delta x$ to $x = (0 + \Delta x) + \Delta x$ (or $2\ \Delta x$, but I find writing it this way makes it clearer what is going on - "simpler" isn't necessarily "better"). At this second step, likewise, treating $0 + \Delta x$ as a prior input in and of itself, we have

$$f([0 + \Delta x] + \Delta x) \approx f([0 + \Delta x]) + [f'([0 + \Delta x])\ \Delta x]$$

which, combining with the previous expression, becomes

$$f([0 + \Delta x] + \Delta x) \approx f(0) + [f'(0)\ \Delta x] + [f'([0 + \Delta x])\ \Delta x]$$

and it is not hard to then continue this process so that we see for $N$ steps,

$$f(0 + N[\Delta x]) \approx f(0) + \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f'(0 + i[\Delta x])\ \Delta x$$

or, if we set $x_i := 0 + i[\Delta x]$, we can say more neatly as

$$f(0 + N[\Delta x]) \approx f(0) + \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f'(x_i)\ \Delta x$$

and to be more general, if we take $N$ steps of suitable, perhaps different, sizes $\Delta x_i$ to reach from $0$ some fixed point $x_0$,

$$f(x_0) \approx f(0) + \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f'(x_i)\ \Delta x_i$$

and then we consider what happens as the steps become arbitrarily fine, at which point we hope - and need to prove - that

$$f(x_0) = f(0) + \left[\lim_{||\Delta|| \rightarrow 0}\ \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f'(x_i)\ \Delta x_i\right]$$

which leads us to define this new operation, given by the limit on the right...

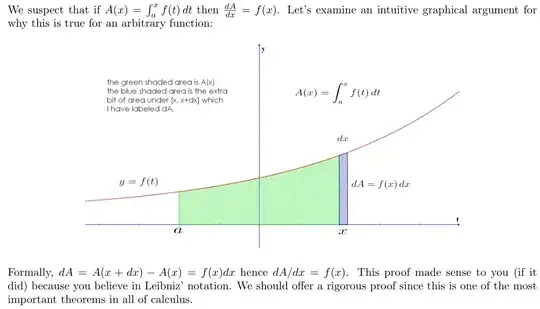

$$\int_{0}^{x_0} f'(x)\ dx := \lim_{||\Delta|| \rightarrow 0}\ \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} f'(x_i)\ \Delta x_i$$