Basic clause patterns can indeed be captured in dependency grammars (DGs) along the lines suggested in the question. However, much rides of course on the language under investigation, since the basic clause patterns in the one language are often distinct from those in the next language. The particular annotation scheme one assumes is also important. Consider in this regard the third pattern listed in the question, i.e. det nsubj ROOT aux dobj. That pattern is apparently assuming that when an auxiliary verb is present, it is NOT the root of the sentence, but rather the content verb is the root. This aspect of the pattern is controversial, since DGs traditionally view the finite verb as the root of the clause, be this finite verb a content verb or an auxiliary verb.

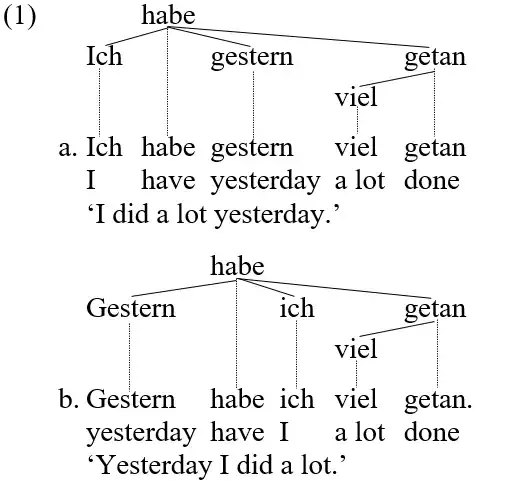

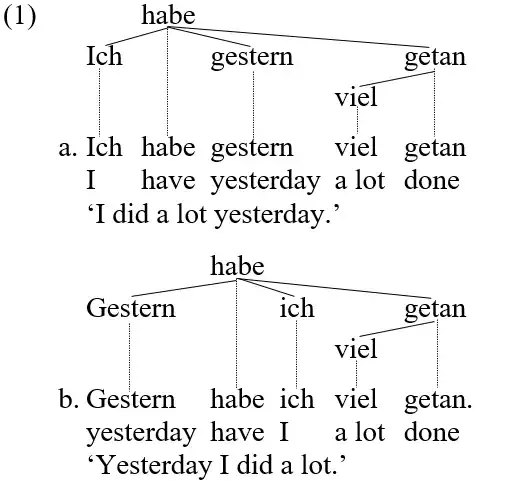

A couple of examples from German can demonstrate the importance of getting the basic annotation scheme right. If the finite verb is the root of the clause as the DG tradition has it, then the V2 trait (verb second) of German matrix clause structure is captured in a straightforward way by the insight that the root verb necessarily has one and only one pre-dependent. Observe the following two trees next; they are of a sentence for which the word order is variable:

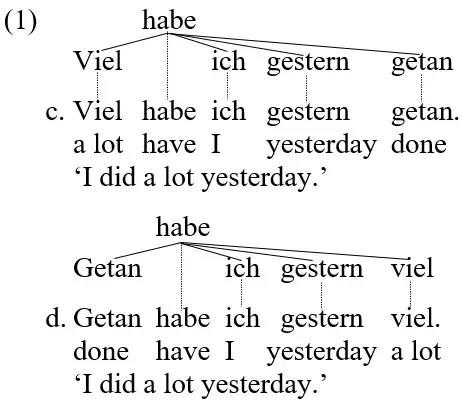

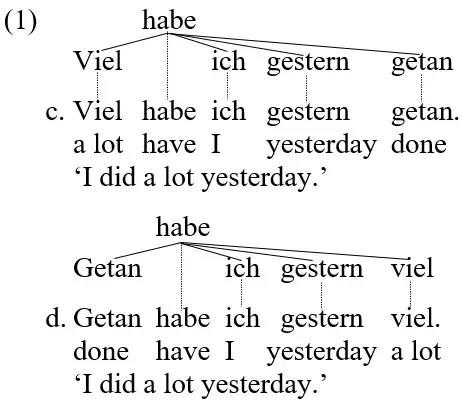

Two more possible word orders are shown with the next trees:

As long as the second position in the clause is occupied by the finite verb (i.e. habe ‘have’), there is much flexibility concerning the constituent that appears in the first position. This insight is captured in DG terms by acknowledging that the root must have one and only one pre-dependent. If the content verb getan ‘done’ were the clause root instead of the auxiliary habe ‘have’, this V2 trait of matrix clause structure would be more difficult to discern because there would be no way to know how many constituents could precede the root. Consider in this regard that in the fourth tree given, i.e. the d-tree, the content verb is in first position.

Let’s consider examples from English next. Embedded finite clauses in English have a predictable basic structure. They are almost always SV (subject + finite verb) -- exceptions do occur, although they are rare, for instance in the event of negative inversion and regarding some dialectal variation. This is true, for instance, of object clauses introduced by that, e.g.

(2) They said that FrankS sentV Jill chocolates.

(3) They said that yesterday FrankS sentV Jill chocolates.

The bolded S and V are marking the subject and finite verb. Embedded interrogative clauses that lack an auxiliary verb also consistently have SV order, e.g.

(4) I wonder whoS sentV chocolate to Jill.

(5) I wonder what FrankS sentV to Jill.

(6) I wonder who FrankS sentV chocolate to.

(7) I wonder to whom FrankS sentV chocolate.

It remains true if an auxiliary verb is present, e.g.

(8) I wonder whoS willV send chocolate to Jill.

(9) I wonder what FrankS willV send to Jill.

(10) I wonder who FrankS willV send chocolates to.

(11) I wonder to whom FrankS willV send chocolates.

(Note that I view modal verbs like will as finite because among the verbs, they appear leftmost in a position where the finite verb generally appears.) It’s also true of relative clauses, e.g.

(12) Jill, who FrankS sentV chocolates to

(13) Jill, who FrankS willV send chocolates to

In all of these examples, the subject in the embedded clause immediately precedes the finite verb, be this finite verb an auxiliary verb or a content verb. Therefore, it does indeed appear that the sequence SV is the most distinctive trait of embedded clauses in English. This insight can be easily captured in a DG approach, but in order to do so, one needs to assume that the finite verb dominates the content verb, not vice versa, for only in this manner is there a direct dependency linking the subject to the finite verb. This one dependency is, then, the core dependency responsible for the most distinctive word trait of embedded clauses.

To sum up, the answer to the question is that the patterns suggested in the question can indeed serve as templates for establishing basic aspects of clause structure in a DG approach to syntax. However, for such an approach to work well, one has to get the basic dependency analysis correct. In particular, one has to be clear and confident about which word order qualifies as the root of the clause.