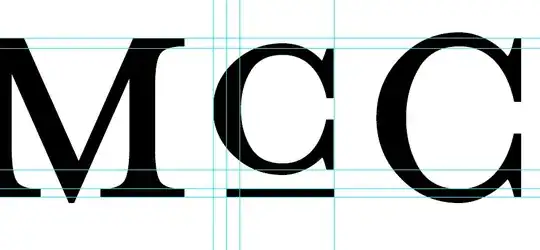

Regarding names like McNeil or McDonald and such, twice recently I have been asked to move the lowercase c up so that the top of the lowercase letter aligns up with tops of the other two uppercase letters to either side of it like MᶜNeil or MᶜDonald, or even so that it sits above them like in M cNeil or M cDonald.

I do not recall seeing this done in most comparable situations.

Do you know why some might consider this necessary ... is it merely a matter of preferred style? And is the history of the different formats known?