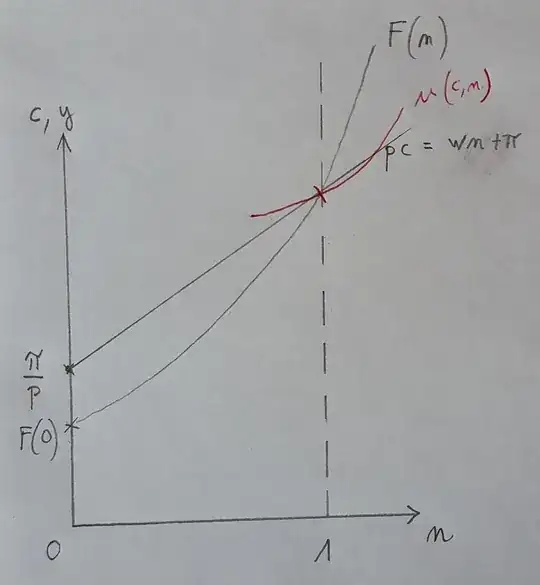

Here is an example where the two are actually compatible: The consumer's utility function $U:\mathbb{R}_+\to\mathbb{R}$ is given by $U(c,1-n_ns)=c-n_s$, the initial labor endowment is $1$ and $F:\mathbb{R}_+\to\mathbb{R}$ is given by $$F(n)=n(1-e^{-n}).$$

This function has IRTS, but still turns a unit of labor into less than one unit of consumption at any amount of input. If you let the price of consumption be $1$ and $w\geq 1$, you have a competitive equilibrium in which nothing is produced and the consumer simply consumes their endowment.

Side rant: The usual definition of IRTS is that when the inputs are multiplied by a number larger than $1$, the resulting output increases more than proportionally. Under this definition, no production function for which an input of $0$ is feasible has IRTS. Even if one restricts oneself to nonzero inputs, the definition does not work the way people seem to think. The standard example of a production function with IRTS is a Cobb-Douglas production function in which the sum of exponents is larger than $1$. The standard definition of IRTS applied to an input combination with some, but not all, entries $0$ would show that IRTS does not hold here. It does work when we restrict ourselves to input combinations that produce a positive output, and the function in the example is of this kind.

However, one can show that no competitive equilibrium exists if one makes the assumption that the consumer prefers to turn some labor into consumption and the production function produces zero output with zero input and is continuous and increasing, and the consumer's utility function is strictly increasing on the interior. For example, with Cobb-Douglas utility, every bundle in which the consumer enjoys both consumption and leisure is better for the consumer than a bundle in which they enjoy only one of these in a positive amount. Since every competitive equilibrium is Pareto efficient by the first welfare theorem (whose assumptions hold here), some amount of consumption must be produced here, and this is not compatible with profit maximization. Indeed, suppose there is an equilibrium with $p$ the price of the consumption good and $w$ the wage. Since the consumer's utility function is strictly increasing on the interior, an optimal consumption bundle can only exist if $p>0$ and $w>0$. Let $c_e$ and $n_e$ be the equilibrium consumption and labor supply. Efficiency requires $c_e>0$ and, therefore, also $n_e>0$. Since the firm can always have a profit of $0$ by using no input, profit maximization implies that

$$pF(n_e)-wn_e\geq 0.$$

But then, $$p F(2n_e)-w 2n_e>p 2F(n_e)- w 2n_e=2\big(p F(n_e)-wn_e\big)\geq p F(n_e)-wn_e.$$ Here, the strict inequality comes from IRTS and the weak inequality from $pF(n_e)-wn_e\geq 0.$ We see that the production plan that use an input of $2n_e$ produces a higher profit than the production plan that uses $n_e$, in contradiction to the firm maximizing profit with a production plan with input $n_e$.