It's a simple question.. What do continents "lay" on? Do they float on water? or are they huge bodies that "emerge" from the sea floor/bed? are they connected to the bottom of the oceans? Hope the question is clear. Don't be afraid to be thorough and scientific in your answer, I'll appreciate it and do everything to understand it.

-

7Turtles. It's turtles, all the way down. – cat Apr 24 '16 at 03:17

3 Answers

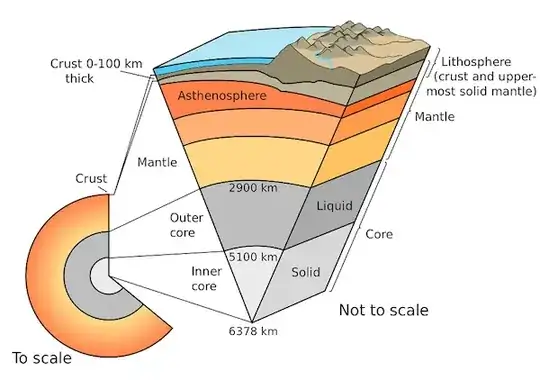

Matan, the continents where we all live "float" on the Earth's mantle. The continents are made out of relatively brittle rock called the "Crust" and the mantle is made out of much more ductile material. The mantle, however, is NOT liquid. It is just much more ductile than the crust so, in geologic time, it can flow (like silly putty). Also, the mantle is much more dense, so the crust doesn't sink into it by gravitational/bouyancy forces alone.

Think of it as a creme brulee. We live on the little hard crust on the top. And there just happens to be a little bit of water on that crust that covers the less-elevated parts.

Now, a little more technical, the crust that makes up the continents and the crust that is under the deep oceans are actually compositionally different. This is because the magma that solidifies to form each of these crusts travels, by partially melting its way up, through different materials and different thicknesses. The consequence of this is that the crust making up the continents is less dense than that making up the bottom of the oceans.

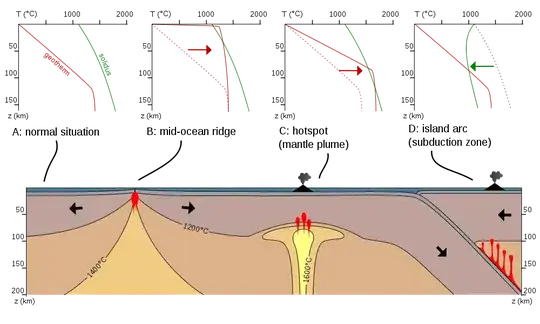

The image above shows the process by which we get new (left) oceanic crust, (right) continental crust, and (middle) a special type of crust like that in Hawaii. Note that when two tectonic plates collide, the more dense one will tend to subduct under the other.

- 947

- 4

- 14

-

1Wow.. Amazing, simply amazing. Astonishing answer! It's must clearer for me now, thanks a lot! – Matan Apr 24 '16 at 10:35

-

-

2You missed out the Cratons, Cratons are the really light, deep, and very old pieces of Continental Crust that have survived since the Precambrian and are really important in defining the tectonic plates we have today, otherwise this is a perfect answer. – Ash Aug 15 '17 at 14:20

[This answer has been highly critisized for using only the oversimplified descriptions used in school textbooks as an answer; the original answer is included only to make sense of the comments]

(I'm not a professional geologist; this is from my personal studies) Lava, essentially. The Earth is molten when you get farther down, and the surface of the planet is made up of large plates of stone, which very slowly get pushed around by huge swirls of lava beneath them.

Note that this is a very simplified explanation, but it seems to answer your question.

- 435

- 3

- 10

-

6Incorrect. The overwhelming majority of the stuff that's under the continents is solid rock, not molten lava/magma. – Gimelist Apr 24 '16 at 04:15

-

1It depends on how deep one interprets "under the continents" to be. I think Anonio strikes the best balance between the lava and solid rock explanations, though I still stand by the lower presence of magma (I avoided the magma/lava explanation for simplicity's sake. That might have been a rookie mistake). – Henry Stone Apr 24 '16 at 09:43

-

Let's define "deep enough" as the place where the stuff under continental crust and oceanic crust is the same. So that would be the mantle. And the mantle is solid. Now, there is a very strong difference between "presence of magma" to "continents laying on magma". What you said implies that there is only or mostly magma. In fact, there are very small amounts of magma in the mantle (up to a few percent of the entire mostly solid rock mass), and even then it occurs in very localised areas. The presence of magma is important for all kinds of things, but it's not the main thing. – Gimelist Apr 24 '16 at 09:53

-

It's as if you would put a box on something on wet sand. Yea, so there's some water between the sand grains. But you wouldn't say the box is placed on water, it's placed on solid sand. – Gimelist Apr 24 '16 at 09:53

-

While I think this particular comment line should be closed (the question has already been answered better), no, it's not like that. It's like saying there is water beneath the sand. It might not be a very complete description (I openly warned that I was oversimplifying), but it is true, and it did answer the question. I understand that you have an extensive background in the field and are well versed on the details; I answered on a 7th grade level, because that is what I teach. The answer is correct; it might not be satisfactory, but it is correct. – Henry Stone Apr 24 '16 at 10:23

-

3The prevalent existence of deep magma is one of the biggest misconceptions about the structure of the Earth. It is overwhelmingly solid and any amount of magma is insignificant. It would be best if you teach it correctly to your 7th graders because otherwise the misconception will linger around. I repeat: There is no concentration of magma that the continents lay on. This is a scientific fact, regardless of whether you think it is true or not. – Gimelist Apr 24 '16 at 21:49

-

With all due respect for precision, "superhot molten rock that flows slowly", or whichever way you wish to describe what goes on beneath the solid tentonic layers, is magma (or lava) to a 7th grader, and to most non-professionals. I would love to go into great detail when teaching, but some detail belongs at later stages of learning. This is one such case.

It does, of course, warrant a disclaimer that it is oversimplified, which I gave.

– Henry Stone Apr 24 '16 at 23:03 -

5But this is not molten rock. This is my point. It is as solid as any rock you would pick up at the surface of the Earth. And to a 7th grader, saying that it is molten rock is incorrect and perpetuates the misconception that there is a magma ocean underneath the crust. Anyway, if you want we can continue this discussion in the chat, or you can open another question: "is there a magma ocean in the Earth?". – Gimelist Apr 25 '16 at 00:30

-

3There are no large bodies of magma in the mantle. We know this because we can measure the propagation of seismic shear waves through the mantle and they propagate through the whole mantle, meaning that it must be solid, because shear waves cannot travel through a liquid. S waves do not propagate through the outer core and this is how we know that it is liquid. – bon Apr 25 '16 at 09:17

-

Let's see what I got from my (limited) knowledge of this topic: The lithisphere is broken into tectonic plates, which move around on the athenosphere (and, arguably, what is beneath it, but...). The athenosphere consists of superhot, viscous rock. It is generally solid, but with melted areas. To the non-professional, and especially 7-graders, "vicous rock, part solid but part melted" is essentially magma (or lava, if you go simple). Yes, the devil is in the details, and technically it's not magma, but whether or not that is a distinction to include depends on the level of the audience. – Henry Stone Apr 25 '16 at 13:09

-

And a completely 100% solid mass would, AFAIK, not be ductile enough to be the key driver of tectonic movement; something more ductile beneath it would. But I am not a geologist, so feel free to point out any factual errors. I am getting interested now, even if this has dissuaded me from ever answering a question again. Sadly, I have not been on SE-EA long enough to have chat privileges... – Henry Stone Apr 25 '16 at 13:09

-

1Actually, the mantle is pretty ductile on geological timescales, despite being almost entirely solid, especially lower down. If you heat a rock up to something like 80% of its melting temperature and then apply some seriously large stresses to it over a long period of time, it will flow very nicely, mostly by diffusion creep. – bon Apr 25 '16 at 18:51

-

3Super hot viscous rock is not like magma to 7 graders. There is a huge difference between the two: one doesn't erupt in volcanoes whereas the second does. You can compare the two to chocolate slightly warned by hands that becomes soft and bends, but is still solid. Magma, on the other hands, is like chocolate on a fountain. 7th graders like chocolate! You can even make a nice demonstration in class. – Gimelist Apr 25 '16 at 20:34

-

2It's like magma to them. And magma is lava, to them. It isn't to us, but that's a pedagogical issue, not an earth science issue. Although I do like the chocolate comparison. But whatever the case, "continents float on lava" is in no way a correct description, it's an extreme oversimplification, and I do not challenge that one bit. Only the value of pressing the detailed distinction onto kids who are already pressed to be there, and possibly adults who want quick answers. I believe that is my closing statement. – Henry Stone Apr 26 '16 at 17:18

-

2@HenryStone So make it not like magma to them. You are the teacher. Teach them the correct. Show them a chocolate out of the fridge. It's hard and solid. Yes, you can bend it with enough force and if you heat it up in your hands. But it's not liquid. It's a solid. Saying it's a liquid is as wrong as saying that the atmosphere is a liquid and the walls of your house are liquid. It's wrong. For adults, and for children. Please do not perpetuate this misconception. – Gimelist Apr 27 '16 at 22:42

-

Sadly, there is not enough focus on each topic to allow such detail. But you have swayed me a bit (I have a similar frustration about electronegativity), and adding a "it's not really lava, rock just gets soft and mushy when there's that much heat and pressure, so it acts a little like lava" is definitely an option. Sadly, schools expect a million topics to zip by, giving little time for any. Sadly. But at least I'm now a bit wiser in the ways of the rocks! Also, the atmosphere is partly governed by fluid dynamics, so in many regards, it IS considered liquid. Just saying. – Henry Stone Apr 28 '16 at 11:33