In order to generate an elliptical orbit, you need to have a force which is equal to the required centripetal force:

$$F=m\frac{v^2}{r}\rightarrow a=\frac{v^2}{r}$$

According to Bertrand's Theorem, this can only be solved with a potential for an inverse square force, or a radial harmonic oscillator potential.

So we cannot attain a circular orbit, is that a problem? No.

I generated a system for our sun, Earth, and moon, dependent on a linear inverse force. What we find is that we need to rescale the Gravitational constant to the negative 22nd order. (For clarity's sake I avoided using astronomical units).

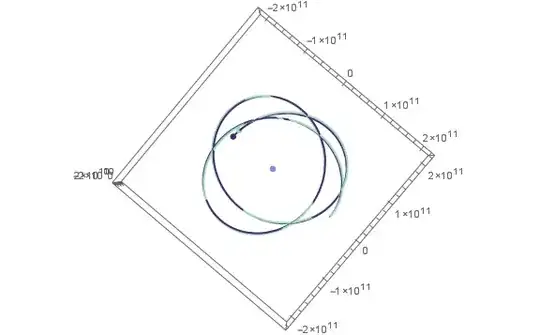

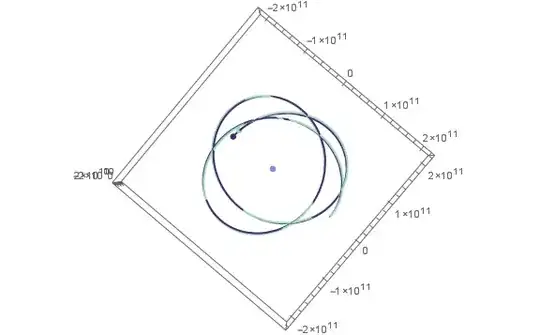

So if we set $G = 6.6740831\times10^{-22}$ we find the following orbit patterns:

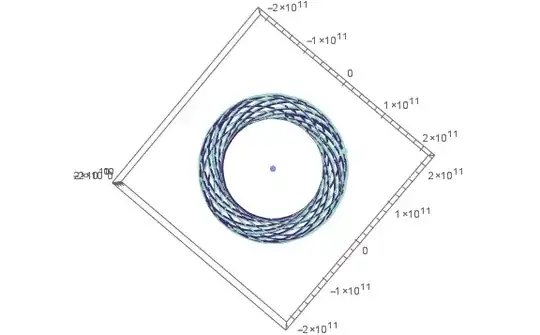

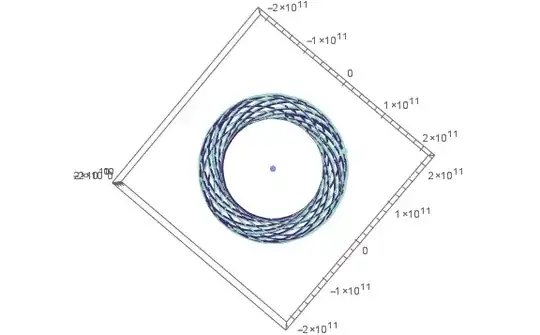

We can further decrease the orbital eccentricity when $G \rightarrow 4\times10^{-22}$

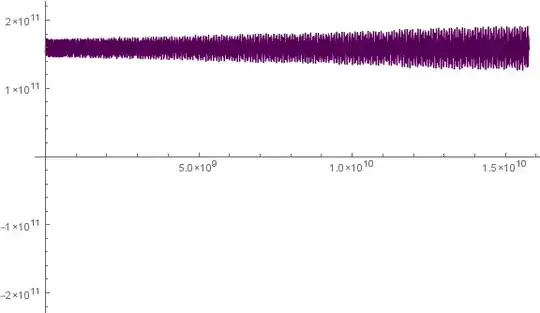

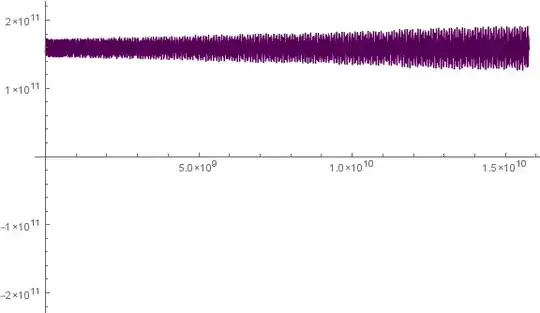

Note however, that in the long term, the eccentricity will always increase, even for optimal $G$, take the following radial Sol-Earth distance over 500y:

There are more problems though, for instance, would a star even form with this Gravity configuration?

Note that in this configuration, the acceleration of gravity due to Earth on its surface would be $0.000375m/s^2$ instead of $9.8m/s^2$

As the gravity drops off more slowly, but is also significantly more massive, a habitable planet would be much more massive, but such massive planets might also more easily form under these parameters.

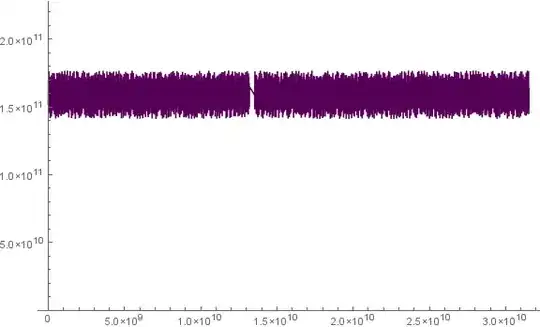

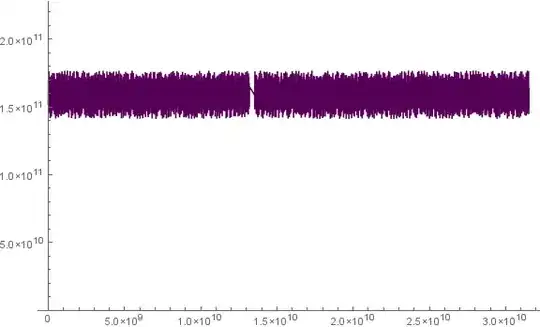

And here is where things get really interesting, if we suppose that our planet has a mass of $m_{earth}=5.97237\times10^{28}$, four orders higher than that of the current Earth, gravity at the same radius would be $3.75m/s^2$, and we get the following 1000 year progression:

My suspicion is that the collapse happens 4 orders of magnitude slower, meaning you would have at least $10^5y$ of stable orbit, possible a million (1Ma).

If you could have a planet with a mass of order $O\left(29\right)$, then you might get a near-stable orbit over evolutionary time scales, however getting such a large concentration of Earth (oxyen, quartz, aluminium, lime, iron, magnesium) might be difficult to attain, except maybe in a late-stage galaxy.

I do think the peculiar circumstances would make the formation of large planets more likely as distance is less of a factor for matter to come together. Consequently we would expect fewer planets, but of higher average mass. However, it is also possible this situation would lead to more uniformity in mass distributions.

You would have to run some galaxy wide gravity calculations for that one, and recalculate the result of the background radiation. These are things beyond my scope.