TL;DR

It's not possible.

Ye Be Warned

Really bad MSPaint skills were involved in the making of this answer. Many artists turned over in their graves. Also, the real physics are a bit more complex, but I'm not a real astronomer so this will have to do for a first-order approximation.

What is Tidal Locking?

Tidal locking is explicitly a function of orbiting another body.

The tides from one body (say, our moon), cause the near side of the other body (Earth, in this case) to be slightly closer than the rest of the planet. Because that mass is closer, it has more gravity than the rest of the planet.

But if the planet is rotating, the bulge moves forward a bit, so it's not directly between the center of the Earth and moon.

This means the force on the east side of the Earth (orange line) is slightly stronger than the force on the west side of the Earth (purple line), resulting in a small, but measurable, net torque. This torque means the Earth is gradually slowing down, and will continue to slow down until one side of the Earth is always facing our moon (which is already tidally locked because it's a lot less massive, so it didn't take as long to slow down).

Of note, this means a slowly-turning planet with a fast-orbiting moon will actually speed up until tidal locking occurs. Also, not shown, as Earth slows down, the distance between Earth and our moon increases. If the Earth were speeding up, the distance would decrease over time.

Tidal Locking by Sharing an Orbit

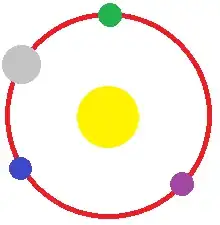

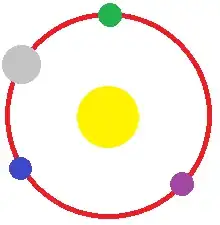

So for two planets to be tidally locked, but not orbiting each other, they have to be tidally locked to something else. The local star is a good candidate. You could have something like this:

The blue, green, and purple planets are orbiting 60° from each other, and they could be tidally locked to the star (so one face of the planet is always looking at the star), which means they'd also be "tidally locked" to each other in the sense that each planet would always see the same face of the other planets.

Note that, to the best of my knowledge, you need a more massive planet orbiting halfway between two of the smaller planets for this to work; though you don't need all three planets -- the grey one plus any of the other three would still orbit. Addendum: it seems the L3 point (purple) is unstable so you don't want to use it anyways, but L4 and L5 (blue and green) are both stable and don't require a large primary (grey). So you could ostensibly have just the grey and blue or green planets of about the same size. Still, it doesn't solve the problem of shading the second planet.

To Your Idea

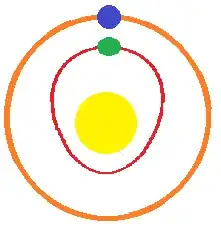

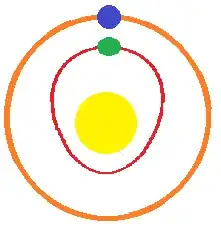

Ok, so we can sort of get tidal locking without the planets orbiting each other, but it's not what you wanted. You're looking for this:

You can do that, but there's a problem. The orbital period is directly related to it's distance. In order for a planet to be in orbit, the centrifugal force from inertia has to exactly offset the centripetal force from gravity. There's less gravity farther from the star, so the more distant planet has to orbit more slowly or it will just fly off into space. Additionally, the length of the orbit is proportional to it's distance ($circumference=2\pi\times radius$). So it's going farther, and it's doing it more slowly, which means the time taken has to be longer.

Geometrically, there's just no way for the outer planet and the inner planet to orbit the star at different distances and orbit in the same amount of time.

So let's say you put the blue planet in a proper orbit, then magically slow the green planet down to the same speed. Now, gravity overcomes centrifugal force, causing the planet to fall, and you end up with a highly elliptical orbit (if it's slow enough, the "orbit" will involve crashing into the star). At the highest point in the orbit, it's traveling the same speed as the other planet, but as soon as it gets closer to the star, it speeds up. The extra speed, combined with the even shorter orbital distance, means it's still orbiting the star faster than the outer planet.

A similar effect happens if you speed up the outer planet. Either it ends up in a highly elliptical orbit, or, if it's fast enough, it flies straight out of the star system, nevermore to be seen. Regardless, it still orbits more slowly than the inner planet, if at all.

Extra

Of note, there are a variety of weird orbital characteristics, such as the outer planet orbiting exactly three times for every twice the inner planet orbits, or their "day" period being some simple ratio of each other's. But none of these involve tidal locking, or one planet always being in the other planet's shadow.

The L2 Point

From comments and other answers, it looks like I need to also address the L2 point. In addition to the above configuration (the grey primary and the blue/green (L4/L5) and purple (L3) secondaries), there are two more Lagrangian points, L1 and L2. L1 is between the sun and the primary, while L2 is behind the primary, opposite the sun.

In this case, the gravity from the nearby planet adds to the gravity from the far away star, meaning the small planet has to go faster to balance out the extra gravity. Right at the L2 point, the extra speed is exactly enough so the outer planet stays right behind the inner planet.

Just what we wanted, right? Well, no. Sorry.

First, I assumed that "twin planets" (from the title) meant the two planets needed to be similar size. In this case, the L2 point is right out, because it requires the outer planet to be much smaller than the inner planet.

Second, for Earth, the outer planet is too far away, and isn't actually shaded by the inner planet, so it doesn't meet the requirements. However, this space.SE answer shows that it is possible, with the correct geometry, to solve this (in our solar system, everything from Mars to Pluto has a perpetually-shaded L2 point; Mercury to Earth do not). So you're ok here as long as you do the math.

Third, most problematically, is the L2 point is extremely unstable. A little nudge in any direction, the the outer planet falls out of the L2 point. From this NASA article, it takes about 30 days to get to Earth's L2 point by coasting. This means it takes about 30 days to fall out of the same point, back to the starting altitude (and much less time to fall out of the primary's shadow).

You get a bit more time if you're sitting in a halo or Lissajous orbit, but you still need to make corrections about once a month. With a different-sized primary, you might get a little more time, but we're still talking maybe a few years of stability. Also, both of those orbits move you (and possibly keep you) completely out of the primary's shadow, so they don't really meet the requirements.

There's just no way to keep a planet in the L2 point for any reasonable length of time without constant, planet-scale thrusters, at which point you might as well just call it magic. My understanding is the WH universe has plenty of techno magic that could accomplish this, but it's not really feasible under normal circumstances. And I'm really hard-pressed to come up with a reason to bother; it would be far cheaper and simpler to just build your colonies on a planet farther from the star (or just accelerate the planet farther from the star) than to keep one planet in another planet's L2 point for any significant amount of time.