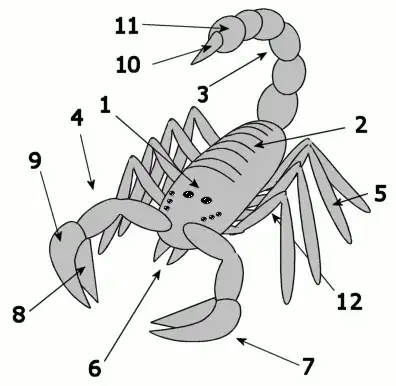

It's important to understand that our "dominance" as it were, is entirely a fluke. There's no intent or drive to make something intelligent; and there's little about our general design that made it even likely.

We just had a series of flukes.

Our ancestors happened to be members of the groups which:

on dividing as single-celled organisms, stayed together in a colony, rather than dispersing. Eventually, individual cells became specialized, creating multi-cellular life.

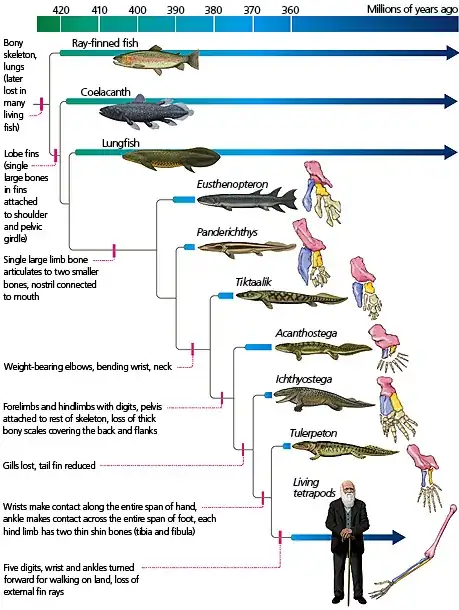

laid down support structures on the inside (vertebrates) rather than the outside (arthropods). This doomed us to never dominating the planet, as the creatures with exoskeletons have always ruled the world, and likely always will, vastly outnumbering us, out-weighing us in terms of biomass, living in a far wider range of environments, outdoing us in just about every possible interpretation of survival, and infesting and living off us.

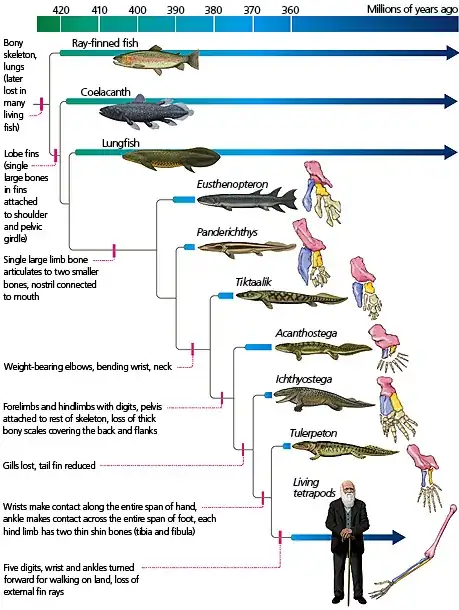

controlled their buoyancy by gulping air into their digestive tract, which eventually branched into fish with swim bladders and lungfish: we came from the lungfish.

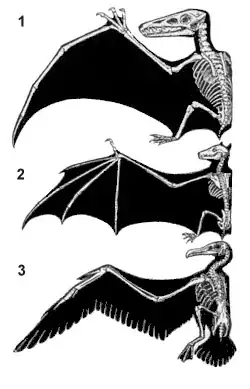

were tetrapods, with four fins, laying the framework for their descendants the quadrupeds (all reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals).

lived in seasonally flooded mangrove swamps or tidal basins, so were regularly exposed to air, developed fins that could grasp onto roots and stalks, and eventually began to spend the majority of time on land... though naturally we'd been beaten to it by millions of years by the arthropods: insects, crabs, etc.

invested in internal maintenance of body heat, which served us well when the skies went dark and the ones who'd chosen external thermoregulation died off.

climbed (brachiated) in trees to became monkeys, this brachiation providing necessary preadaptations to bipedalism and tool-holding.

had their tails atrophy away (why? We don't know!) to become the apes, resulting in bipedalism rather than kangaroo-style tripedalism.

lived on water-based prey, likely in mangrove swamps (which may also have lost us our fur covering), so had ample supplies of essential fatty acids for surplus brain growth.

were large-brained generalists: omnivorous, adventurous, opportunistic and inquisitive. This led us to start using tools.

were socially gregarious enough to share the abilities that tools gave.

had a descended larynx, such that complex speech could be developed, and thence storytelling and passing on of knowledge, eventually leading to writing.

It's language -- and more importantly, the preservation of knowledge that it permitted -- which meant agriculture became a thing, and later, sharing of tool designs, mathematics and science led to the industrial revolution.

We could have accomplished all this in ANY body form that had language and a large enough brain to transfer concepts -- none of the rest mattered.

And it's a good thing that form did NOT matter, as the form we have, with its vast flaws, is a result of all these accidents. With only two legs, we are essentially crippled if we lose one, compared to most quadrupeds who can easily adapt. We get backaches, hernias, obesity, and varicose veins, all because of this darn bipedal stance that the mammalian quadrupedal frame was not formed to take -- we've adapted to it, but it's an obvious bodge job, requiring a reworking of all our insides that makes childbirth almost nightmarish and our children incapable of escaping on foot for years.

None of this was required. It was all just a fluke of chance, unlikely to be repeated anywhere else.

But language, and complex, curious brains? Very likely to eventually be repeated on any planet with life.

Whether that inevitably leads to tool use, and whether tool use inevitably leads to space travel, I cannot say... but to me, intelligence and curiosity beget desire to accomplish things; a desire to accomplish things in an intelligent being, becomes a seeking for methods to accomplish that end; and so tool use feels inevitable, and we see it in most species that we consider even slightly intelligent. In human cultures at least, being able to see the sky also seems to inevitably lead to observing it, and curiosity leads to wanting to explore a thing more closely.

Edit: the above answer focused on the core assumption that our form was inevitable. But I guess I might as well address the other assumptions, though others have already done this well.

uses some liberal wording ... not meant to be academically rigorous

Understood: I shall avoid definitional nitpicks.

Apex species - [...] For example, humans, tigers and orcas. Intelligence is a prerequisite unless you can plausibly explain why it is not required.

Wouldn't a plausible explanation be "the only one in your list of 'humans, tigers and orcas' which even exhibits tool use is the anthropocentric one"? The tool-using species that we are aware of (see list below) tend to be generalists and scavengers, not apex predators.

Without fine manipulators we would not be able to use tools,

Tool use has been observed in the following animals:

- Primates (humans, chimps, bonobos, orangutans, capuchins, baboons, mandrills, macaques; earliest known evidence of tool use in protohumans 3.39 million years ago)

- Other mammals (bears, elephants, otters, dolphins, kangaroos)

- Cephalopods

- Reptiles (alligators, crocodiles)

- Insects (ants, wasps)

- Fish (wrasses, stingrays, damselfish, cichlids, archerfish)

- Birds (finches, corvids, warblers, parrots, vultures, nuthatches, gulls, owls, and herons).

Not all of these use hands or "fine manipulators". In fact, they can be said to fall into these categories:

- Hands/feet: primates, bears, otters, kangaroos, some insects.

- Beaks/mouths/mandibles: dolphins, reptiles, insects, fish, birds, ants.

- Limbs without fine manipulators: insects, fish.

- Tentacles: primates, elephants, cephalopods.

and there's no sensible reason to develop tentacles on land so that only leaves hand-like clusters of extremities.

I admit I bent the term "tentacle" above, to include all prehensile (="grasping") things other than hands.

The list of prehensile things includes (non-exhaustive list):

- Hands/feet: just about anything that climbs trees, primates, bears, otters, kangaroos.

- Tails: reptiles (lizards, geckos, chameleons, skink), seahorses, various fossil animals.

- Tongues: giraffes.

- Noses: elephants, tapirs.

- Penises: tapirs, dolphins, maybe elephants?

- Lips: manatee, sturgeon, orangutan, horses, rhinos

Given this range of fleshy grasping items, most of which are on land, it seems strange to assert that tentacle-style grasping on land is not something that would be selected for.

There's no conceivable need for more than two hands that wouldn't be outweighed by the inefficiency of having to supply them with energy.

The Orangutan would beg to differ.

In fact, the following creatures have more than two separately-controllable prehensile appendages, tailed ones often having five, and some having over ten:

- mammals (monkeys, opossum, anteater, binturong, kinkajou, harvest mouse, porcupines, tree pangolin, rat, potoroidae, monito del monde)

- reptiles (kink, chameleon, snakes, gecko, alligator-lizards)

- amphibians (salamanders)

- cephalopods (octopi, squid, cuttlefish, nautiluses)

- Also just about anything other than birds which regularly climbs trees.

Being bipedal gives us a combination of balance, fast/slow modes of travel, excellent ability to overcome obstacles and chase prey or escape predators.

Being bipedal also gives us hernias, instability, inability to run from predators for years, hip, back, and circulatory problems that quadrupeds don't have, agonizingly painful childbirth, and so forth: from a medical point of view, the changes to our body that were required for bipedalism are an absolute disaster.

Having more than two legs would imply a lack of hands due to efficiency constraints (how many intelligent creatures have you seen with 4 legs and 2 arms?)

Our 4-limbed skeleton is entirely because we developed from a tetrapodal fish that happened to have four fins and a tail. Skeletal changes are, evolutionarily speaking, slow and hard. The formation of a new bone almost never happens, let alone the formation of an entirely new limb. This can happen as a developmental mutation (merging of two embryos, chimeraism), but not, I believe, as a genetic one, so the mutation cannot be inherited.

A head containing the most critical sensory organs makes sense.

I agree - it's also important to have the sensors near the central nervous system, because nerve length relates to reaction time. However, there are other patterns such as that of the octopus' distributed nervous system, also seen in some of the larger dinosaurs.

Having the primary method of vocalization in the head also makes sense

Agreed. Though really low bassy sounds might be better coming from as low as possible. And for aquatics and fliers, of course, it's irrelevant.

Concentrating functions like eating/breathing/talking into one system is very efficient (again, virtually every organism we know of does this - certainly every dominant organism anyways)

We're the only organism I know of that does this without separation of the systems, and it's super stupid. Our descended larynx makes diving and speech easier, but makes choking to death common (1st leading cause of infantile death, 4th leading cause of death among preschoolers, and 4th leading cause of unintentional death overall). It also means we can't breathe at the same time as eat or drink. [Edit: also apparently seen in chimps, macaques, and some deer].

The most variation I can conceive of would be skin composition

This may be the saddest indictment of how modern educational systems kill imagination that I have ever read.

they would spend tens or hundreds of thousands of years using their intelligence to craft environmental stabilizers like clothing and shelter, so having fur or even just tough skin would have become unnecessary long ago.

The only reason you can see our skin now is because of a past environmental pressure (I'd argue for a semiaquatic stage, others believe it was to improve cooling, or sexual selection). It was not due to clothes-wearing or the invention of AC (in fact, we now have to wear clothes because of our hairlessness). Bodily hairlessness is now maladaptive for civilized-us. Head hair and beards that have to be constantly trimmed and managed is also maladaptive. Head and facial hair that clearly signals age is maladaptive, unless aging is a sexual characteristic - which it is not, for most.

In short, in a large population with no significant evolutionary pressures, and technological solutions like hair dye and beard trimmers to resolve any issues which might affect their reproductive success rates, "Unnecessary" is not an evolutionarily selective force.

how many intelligent creatures have you seen with 4 legs and 2 arms?Do centaurs count? I've seen them in several different movies... – Mason Wheeler Sep 07 '15 at 13:01conceivably,no sensible, etc. Considering that some (or all) of these show fallibility, at least under some context, I think you might want to consider being less liberal in the future; i.e. I don't think your word choice was effective here. – kettlecrab Sep 08 '15 at 04:45There's no conceivable need for more than two hands that wouldn't be outweighed by the inefficiency of having to supply them with energyYou've obviously done absolutely no DIY or mechanicing, activities during which about 80% of your time is spent wishing for a third hand! – Grimm The Opiner Sep 10 '15 at 08:20life on earth isn't that roughthat's a very earth-centric view. Life on earth isn't rough for us because we have specifically evolved to adapt to life on earth. Life that evolved on planets with higher average temperatures, lower gravity, and lots and lots more sunlight would find earth to be inhospitably cold, with all their technology and body not working as efficiently due to difference in gravity, and not being able to harvest sunlight as easily for their brand of "photosynthesis". – Lie Ryan Sep 11 '15 at 01:26