I found this image on Harvard.edu:

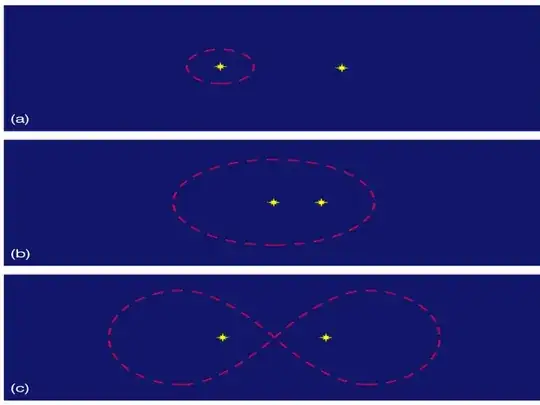

In it, you can see the different types of orbits that are possible for a planet in a binary star system. The figure-8 orbit (my favorite ;) is described as "improbable, though stable". The article does note that maintaining an even temperature over time on any binary-star planet would be problematic, due to the variation in total sunlight exposure at different periods of the orbit. From this we could deduce that the seasons on such a planet, if it were able to support life at all, are likely to be pretty extreme. That's ok, though; you'll just have to work that into your scenario. Might make things interesting ;)

I'll go through the three scenarios in order, ending with the figure-8 example. Let's start with the case where the planet orbits one star close in, while the other star orbits at some distance (figure a). Here you would have the usual seasonal variations in temperatures, plus the additional heat of the more distant, but still hot second star. The magnitude of the extra heating effect depends on two things: the distance between the two stars, and their relative sizes. For example, the extra heat from a second sun the same size as the first, orbiting at the same distance as Jupiter from our sun, would amount to about 5.6% at the height of extra-solar "summer". I put this "summer" in quotes because it's in addition to the regular seasons, and will happen at various times of the year as the relative positions of the two suns change. In general, once per year, on a certain day, the first sun will rise exactly as the second sun sets. On that day, the extra-solar heating effect will be at its maximum. Because of its distance from the Sun, Jupiter orbits once every twelve years; a second sun orbiting at the same distance could be expected to have the same orbital period. So one year, this "equinox" would happen in January, in which case the winter would be milder than normal; six years later, it would happen in July, making the summer extra-hot. The magnitude and frequency of these changes could be adjusted by adjusting the size and/or distance of the second sun.

Now let's look at the case where the two stars orbit close together, while the planet orbits the pair of them. In this scenario, the suns orbit each other faster than the planet orbits the suns, producing wildly varying temperatures on a short timescale. In one recently-discovered binary system of this type, for example, the planet orbits once every 181 days, while the suns come around every 21 days. During this three-week period, you'll see the two suns pull apart and come together again (likely eclipsing one another) in the sky, with sunsets happening either simultaneously or, at most, an hour or two apart. When one sun eclipses the other, solar radiation at the planet's surface could approach 1/2 of its peak level; with this happening twice a month, weather patterns could get pretty extreme. There's presently no scientific consensus on exactly how that might play out, so you're probably free to invent what you'd like in terms of sudden blizzards, thunderstorms, flash floods, gigantic hail, or whatever. In addition to this, there would also be the regular ebb and flow of solar winter and summer as the planet tilts back and forth on its axis - in case you needed things any more chaotic than they were. When the suns eclipse in the dead of winter, temperatures could plummet to antarctic levels; any life-forms that plan to inhabit this planet year-round had better have some kind of survival strategy in place.

Now let's check out the figure-8 system.

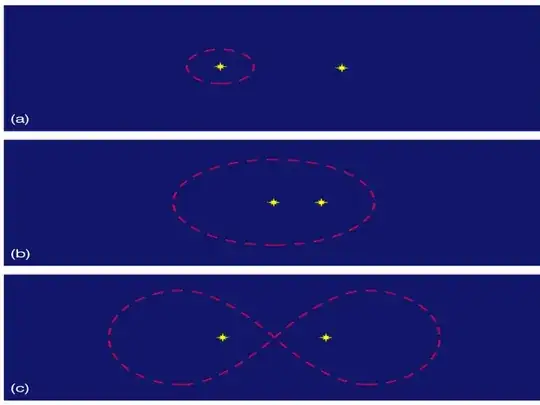

This one is interesting. In real life, this type of system is probably very rare, if it exists at all, because the orbital velocities would have to be so precise in order to make it stable. However, it could exist, and I think it's cool, so I'm going to tell you about it. This system has the most extreme seasonal patterns of the three; compared with Earth, it's likely to experience something like twice as much difference between its maximum and minimum temperatures throughout the year. This planet has kind of a double year, as it orbits each sun once, and throughout that period its surface temperature is affected by two things:

1. the squares of the distances between the planet and each of its two suns, and

2. the angle at which the planet is tilted towards each of those suns.

These two overlapping effects mean that seasons will be very different at different latitudes.

The seasons at the equator are easiest to understand, because the effects of tilt are relatively negligible. Here, as the year progresses, you would see one sun come out from literally behind the other one, where it will have gone into eclipse, an event which could last from two to twelve hours, depending on the size of the planet's orbit and the relative sizes and distances of the suns. Those hours will mark the only time in the planet's year when it will be warmed by only one sun, and therefore (all else being equal) the coldest day of the year. This is still the equator, of course; however cold it may be, it's still the hottest place on the planet - and it's about to get much hotter. After the solstice-eclipse, the two suns will grow farther apart, while the more distant sun will grow larger and brighter in the sky. Depending on the eccentricity of the orbits, the nearer sun may also be coming nearer at this time. Meanwhile, the consecutive sunsets and and sunrises are happening further and further apart; the day grows longer (and hotter) while the night shrinks to nothing. At the peak of this "summer", one sun will rise just as the other sets, creating a 24-hour day - the hottest day of the year.

It's also possible that one of the suns could be somewhat larger and hotter than the other, in which case every other winter will be correspondingly longer and colder than the last, as the planet takes a wider swing around a smaller, colder star.

At the poles, things play out differently, and depend largely on which way the planet is tilting relative to the suns. At the extreme end you could have a pole that tilts furthest away from both suns just at the moment when they're eclipsing each other, and even the equator is feeling the chill. On the other hand, the opposite pole will be tilting toward the suns on that day, experiencing a 24-hour day of arctic summer solstice. That day could also happen during spring or fall, and it's likely to change every year, because as the planet is orbiting each sun in turn, they're also orbiting each other. So although the planet's tilt remains constant, the point in the year when it tilts toward any given sun can and will change. If the orbits develop some kind of resonance pattern, those changes could be predictable and consistent - a super-cold winter every third year, perhaps, with the bi-solar convergence falling in spring or fall the next two years. If there is no resonance, the day of convergence could shift by 17 weeks per year, or 3 days, or any amount, in either direction. When the planet passes in between the two suns, the poles will also experience a 24-hour day, although depending on the tilt, only one of the two suns may be visible. In fact, during that traversal, no part of the planet anywhere will be in darkness.

I hope this gives you some ideas :)