SMC protein

SMC proteins represent a large family of ATPases that participate in many aspects of higher-order chromosome organization and dynamics.[1][2][3]

The term SMC originally derived from a mutant strain in Saccharomyces cerevisiae named smc1 (stability of mini-chromosomes 1), which was identified based on its defect in maintaining the stability of mini-chromosomes.[4] After the gene product of SMC1 was characterized[5], and homologous proteins were found to be essential for chromosome structure and dynamics in many organisms, the acronym SMC was redefined to stand for Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes.[6]

Classification

Eukaryotic SMCs

Eukaryotes have at least six SMC proteins in individual organisms, and they form three distinct heterodimers with specialized functions:

- SMC1-SMC3: A pair of SMC1 and SMC3 constitutes the core subunits of the cohesin complexes involved in sister chromatid cohesion.[7][8][9]

- SMC2-SMC4: A pair of SMC2 and SMC4 acts as the core of the condensin complexes implicated in chromosome condensation.[10][11]

- SMC5-SMC6: A pair of SMC5 and SMC6 functions as part of a yet-to-be-named complex implicated in DNA repair and checkpoint responses.[12]

The pairings of SMC proteins in eukaryotes, SMC1-SMC3, SMC2–SMC4, and SMC5–SMC6, are highly specific and invariant; no exceptions to these combinations have been reported to date. Sequence comparisons reveal that SMC1 and SMC4, as well as SMC2 and SMC3, share a high degree of similarity, while SMC5 and SMC6 form a more distinct clade.[13] It is hypothesized that the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) possessed all six SMC proteins. While SMC1–4 are conserved in all known eukaryotic species, some lineages have lost SMC5 and SMC6 during evolution,[14] suggesting that the SMC5/6 complex may not be strictly essential for eukaryotic cell viability.

In addition to the six subtypes, some organisms have variants of SMC proteins. For instance, mammals have a meiosis-specific variant of SMC1, known as SMC1β.[15] The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans has an SMC4-variant that has a specialized role in dosage compensation.[16]

The following table shows the SMC proteins names for several model organisms and vertebrates:[17]

| Subfamily | Complex | S. cerevisiae | S. pombe | C. elegans | D. melanogaster | Vertebrates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMC1α | Cohesin | Smc1 | Psm1 | SMC-1 | DmSmc1 | SMC1α |

| SMC2 | Condensin | Smc2 | Cut14 | MIX-1 | DmSmc2 | CAP-E/SMC2 |

| SMC3 | Cohesin | Smc3 | Psm3 | SMC-3 | DmSmc3 | SMC3 |

| SMC4 | Condensin | Smc4 | Cut3 | SMC-4 | DmSmc4 | CAP-C/SMC4 |

| SMC5 | SMC5-6 | Smc5 | Smc5 | C27A2.1 | CG32438 | SMC5 |

| SMC6 | SMC5-6 | Smc6 | Smc6/Rad18 | C23H4.6, F54D5.14 | CG5524 | SMC6 |

| SMC1β | Cohesin (meiotic) | - | - | - | - | SMC1β |

| SMC4 variant | Dosage compensation complex | - | - | DPY-27 | - | - |

Prokaryotic SMCs

The evolutionary origin of SMC proteins is ancient, and homologs are widely conserved in both bacteria and archaea.[14]

- SMC (canonical type): Many bacteria (e.g., Bacillus subtilis) and archaea possess canonical SMC proteins that closely resemble their eukaryotic counterparts.[18] These bacterial and archaeal SMCs form homodimers and associate with regulatory subunits to form condensin-like complexes, SMC-ScpAB. It is hypothesized that the eukaryotic ancestor (most likely the Asgard archaeon) possessed two types of SMC proteins: a canonical SMC and an SMC5/6-related SMC. Gene duplications of these two ancestral types are thought to have given rise to the six SMC subfamilies present in the last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA): SMC1–4 evolved from the canonical lineage, while SMC5 and SMC6 evolved from the SMC5/6-related lineage.[14]

- MukB: In some γ-proteobacteria, including Escherichia coli, SMC function is carried out by a distantly related protein called MukB. [19] MukB also forms homodimers and, together with regulatory subunits, assembles into a MukBEF complex, which performs condensin-like functions in organizing bacterial chromosomes.

- MksB/Jet/Ept: A third type of prokaryotic SMC protein, known as MksB, has been identified in certain bacterial species. Like MukB, MksB forms a distantly-related condensin-like complex, MksBEF.[20] More recently, a variant complex called MksBEFG, which includes a nuclease subunit MksG, has been shown to function in plasmid defense.[21][22] In other bacterial lineages, orthologous systems have been identified, including JetABCD[23][24] and EptABCD.[25] These systems are collectively referred to as the Wadjet family of SMC-like complexes.

Subunit composition of SMC protein complexes

The subunit composition of SMC protein complexes varies across domains of life. The table below summarizes the representative complexes found in eukaryotes and prokaryotes, using vertebrate nomenclature for the eukaryotic subunits. Notably, the eukaryotic SMC5/6 complex contains kite (kleisin interacting tandem winged-helix elements) subunits[26] instead of HEAT-repeat subunits,[27] making it structurally more similar to prokaryotic complexes such as SMC–ScpAB, MukBEF, and MksBEF. However, unlike their typically homodimeric prokaryotic counterparts, both the SMC and kite subunits in the SMC5/6 complex are heterodimeric, resulting in a more elaborate subunit architecture.

| Subunit type | condensin I | condensin II | cohesin | SMC5/6 | SMC-ScpAB | MukBEF | MksBEFG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMC | SMC2 | SMC2 | SMC3 | SMC5 | SMC | MukB | MksB |

| SMC | SMC4 | SMC4 | SMC1 | SMC6 | SMC | MukB | MksB |

| kleisin | CAP-H | CAP-H2 | RAD21 | Nse4 | ScpA | MukF | MksF |

| HEAT-A | CAP-D2 | CAP-D3 | NIPBL/Pds5 | - | - | - | - |

| HEAT-B | CAP-G | CAP-G2 | STAG1/2 | - | - | - | - |

| kite-A | - | - | - | Nse1 | ScpB | MukE | MksE |

| kite-B | - | - | - | Nse3 | ScpB | MukE | MksE |

| SUMO ligase | - | - | - | Nse2 | - | - | - |

| nuclease | - | - | - | - | - | - | MksG |

SMC-related proteins

In a broader sense, several proteins with structural similarities to SMC are considered members of the SMC superfamily.

- In eukaryotes, Rad50 is a well-known SMC-related protein involved in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks.[28]

Molecular structure and activity

.png)

Primary structure

SMC proteins are 1,000-1,500 amino-acid long. They have a modular structure that is composed of the following domains:

- Walker A ATP-binding motif

- coiled-coil region I

- hinge region

- coiled-coil region II

- Walker B ATP-binding motif; signature motif

Secondary and tertiary structure

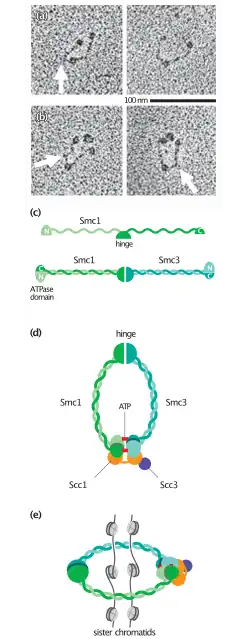

SMC dimers form a V-shaped molecule with two long coiled-coil arms.[36][37] To make such a unique structure, an SMC protomer is self-folded through anti-parallel coiled-coil interactions, forming a rod-shaped molecule. At one end of the molecule, the N-terminal and C-terminal domains form an ATP-binding domain. The other end is called a hinge domain. Two protomers then dimerize through their hinge domains and assemble a V-shaped dimer.[38][39] The length of the coiled-coil arms is ~50 nm long. Such long "antiparallel" coiled coils are very rare and found only among SMC proteins (and their relatives such as Rad50). The ATP-binding domain of SMC proteins is structurally related to that of ABC transporters, a large family of transmembrane proteins that actively transport small molecules across cellular membranes. It is thought that the cycle of ATP binding and hydrolysis modulates the cycle of closing and opening of the V-shaped molecule. Still, the detailed mechanisms of action of SMC proteins remain to be determined.

Loop extrusion activity

Recent studies have highlighted loop extrusion as a conserved molecular activity shared by all SMC protein complexes. Single-molecule analyses have demonstrated that condensin,[40] cohesin,[41][42] and the SMC5/6 complex [43] are each capable of extruding DNA loops in an ATP-dependent manner. During loop extrusion, the ATPase cycle of the SMC subunits is thought to be coupled with dynamic and multivalent interactions between various subunits and DNA. These interactions likely occur in multiple modes, making the molecular mechanism of loop extrusion highly complex and still incompletely understood.[44][45]

International SMC meetings

Active research on SMC proteins began in the 1990s. As global interest in this field increased, international meetings dedicated to SMC proteins have been held regularly since the 2010s. These meetings, which are organized approximately every two years, cover a wide range of topics reflecting the diverse functions of SMC protein complexes, from bacterial chromosome segregation to human genetic disorders.

- The 0th International SMC meeting(The 18th IMCB Symposium)“SMC proteins: from molecule to disease”, November 29, 2013, Tokyo, Japan.

- The 1st International SMC meeting(EMBO Workshop)“SMC proteins: chromosomal organizers from bacteria to human”, May 12-15, 2015, Vienna, Austria.

- The 2nd International SMC meeting[46] “SMC proteins: chromosomal organizers from bacteria to human”, June 13-16, 2017, Nanyo, Yamagata, Japan.

- The 3rd International SMC meeting[47](EMBO Workshop)“Organization of bacterial and eukaryotic genomes by SMC complexes”, September 10-13, 2019, Vienna, Austria.

- The 4th International SMC meeting (Biochemical Society of the UK)“Genome Organisation by SMC protein complexes”, September 27-30, 2022, Edinburgh, UK.

- The 5th International SMC meeting[48](NIG & RIKEN International Symposium 2024)“SMC complexes: orchestrating diverse genome functions”, October 15-18, 2024, Numazu, Shizuoka, Japan.

Genes

The following human genes encode SMC proteins:

See also

References

- ↑ Jeppsson K, Kanno T, Shirahige K, Sjögren C (2014). "The maintenance of chromosome structure: positioning and functioning of SMC complexes". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 15 (9): 601–614. doi:10.1038/nrm3857. PMID 25145851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Uhlmann F (2016). "SMC complexes: from DNA to chromosomes". Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17 (7): 399–412. doi:10.1038/nrm.2016.30. PMID 27075410.

- ↑ Yatskevich S, Rhodes J, Nasmyth K (2019). "Organization of chromosomal DNA by SMC complexes". Annu. Rev. Genet. 53: 445–482. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-112618-043633. PMID 31577909.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Larionov VL, Karpova TS, Kouprina NY, Jouravleva GA (1985). "A mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with impaired maintenance of centromeric plasmids". Curr Genet. 10 (1): 15–20. doi:10.1007/BF00418488. PMID 3940061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Strunnikov AV, Larionov VL, Koshland D (1993). "SMC1: an essential yeast gene encoding a putative head-rod-tail protein is required for nuclear division and defines a new ubiquitous protein family". J. Cell Biol. 123 (6 Pt 2): 1635–1648. doi:10.1083/jcb.123.6.1635. PMID 8276886.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Strunnikov AV, Hogan E, Koshland D (1995). "SMC2, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae gene essential for chromosome segregation and condensation, defines a subgroup within the SMC family". Genes Dev. 9 (5): 587–599. doi:10.1101/gad.9.5.587. PMID 7698648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Michaelis C, Ciosk R, Nasmyth K (1997). "Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids". Cell. 91 (1): 35–45. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80007-6. PMID 9335333.

- ↑ Guacci V, Koshland D, Strunnikov A (1998). "A direct link between sister chromatid cohesion and chromosome condensation revealed through the analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae". Cell. 91 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)80008-8. PMC 2670185. PMID 9335334.

- ↑ Losada A, Hirano M, Hirano T (1998). "Identification of Xenopus SMC protein complexes required for sister chromatid cohesion". Genes Dev. 12 (13): 1986–1997. doi:10.1101/gad.12.13.1986. PMC 316973. PMID 9649503.

- ↑ Hirano T, Kobayashi R, Hirano M (1997). "Condensins, chromosome condensation complex containing XCAP-C, XCAP-E and a Xenopus homolog of the Drosophila Barren protein". Cell. 89 (4): 511–21. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80233-0. PMID 9160743.

- ↑ Ono T, Losada A, Hirano M, Myers MP, Neuwald AF, Hirano T (2003). "Differential contributions of condensin I and condensin II to mitotic chromosome architecture in vertebrate cells". Cell. 115 (1): 109–21. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00724-4. PMID 14532007.

- ↑ Fousteri MI, Lehmann AR (2000). "A novel SMC protein complex in Schizosaccharomyces pombe contains the Rad18 DNA repair protein". EMBO J. 19 (7): 1691–1702. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.7.1691. PMC 310237. PMID 10747036.

- ↑ Cobbe N, Heck MM (2004). "The evolution of SMC proteins: phylogenetic analysis and structural implications". Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 (2): 332–347. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh023. PMID 14660695.

- 1 2 3 Yoshinaga M, Inagaki Y (2021). "Ubiquity and Origins of Structural Maintenance of Chromosomes (SMC) Proteins in Eukaryotes". Genome Biol Evol. 13 (12): evab256. doi:10.1093/gbe/evab256. PMID 34894224.

- ↑ Revenkova E, Eijpe M, Heyting C, Gross B, Jessberger R (2001). "Novel meiosis-specific isoform of mammalian SMC1". Mol. Cell. Biol. 21 (20): 6984–6998. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.20.6984-6998.2001. PMC 99874. PMID 11564881.

- ↑ Chuang PT, Albertson DG, Meyer BJ (1994). "DPY-27:a chromosome condensation protein homolog that regulates C. elegans dosage compensation through association with the X chromosome". Cell. 79 (3): 459–474. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90255-0. PMID 7954812. S2CID 28228489.

- ↑ Schleiffer, Alexander; Kaitna, Susanne; Maurer-Stroh, Sebastian; Glotzer, Michael; Nasmyth, Kim; Eisenhaber, Frank (March 2003). "Kleisins: A Superfamily of Bacterial and Eukaryotic SMC Protein Partners". Molecular Cell. 11 (3): 571–575. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00108-4. ISSN 1097-2765. PMID 12667442.

- ↑ Britton RA, Lin DC, Grossman AD (1998). "Characterization of a prokaryotic SMC protein involved in chromosome partitioning". Genes Dev. 12 (9): 1254–1259. doi:10.1101/gad.12.9.1254. PMID 9573042.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Niki H, Jaffé A, Imamura R, Ogura T, Hiraga S (1991). "The new gene mukB codes for a 177 kd protein with coiled-coil domains involved in chromosome partitioning of E. coli". EMBO J. 10 (1): 183–193. doi:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07935.x. PMID 1989883.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Petrushenko ZM, She W, Rybenkov VV (2011). "A new family of bacterial condensins". Mol. Microbiol. 81 (4): 881–896. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07763.x. PMID 21752107.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Böhm K, Giacomelli G, Schmidt A, Imhof A, Koszul R, Marbouty M, Bramkamp M (2020). "Chromosome organization by a conserved condensin-ParB system in the actinobacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum". Nat Commun. 11 (1): 1485. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.1485B. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15238-4. PMID 32198399.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Weiß M, Giacomelli G, Assaya MB, Grundt F, Haouz A, Peng F, Petrella S, Wehenkel AM, Bramkamp M (2023). "The MksG nuclease is the executing part of the bacterial plasmid defense system MksBEFG". Nucl Acids Res. 51 (7): 3288–3306. doi:10.1093/nar/gkad130. PMID 36881760.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Deep A, Gu Y, Gao YQ, Ego KM, Herzik MA Jr, Zhou H, Corbett KD (2022). "The SMC-family Wadjet complex protects bacteria from plasmid transformation by recognition and cleavage of closed-circular DNA". Mol Cell. 82 (21): 4145–4159.e7. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2022.09.008. PMID 36206765.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Liu HW, Roisné-Hamelin F, Beckert B, Li Y, Myasnikov A, Gruber S (2022). "DNA-measuring Wadjet SMC ATPases restrict smaller circular plasmids by DNA cleavage". Mol Cell. 82 (24): 4727–4740.e6. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2022.11.015. PMID 36525956.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Panas MW, Jain P, Yang H, Mitra S, Biswas D, Wattam AR, Letvin NL, Jacobs WR Jr (2014). "Noncanonical SMC protein in Mycobacterium smegmatis restricts maintenance of Mycobacterium fortuitum plasmids". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111 (37): 13264–13271. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11113264P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414207111. PMID 25197070.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Palecek JJ, Gruber S (2015). "Kite Proteins: a Superfamily of SMC/Kleisin Partners Conserved Across Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryotes". Structure. 23 (12): 2183–2190. doi:10.1016/j.str.2015.10.004. PMID 26585514.

- ↑ Yoshimura SH, Hirano T (2016). "HEAT repeats – versatile arrays of amphiphilic helices working in crowded environments?". J Cell Sci. 129 (21): 3963–3970. doi:10.1242/jcs.185710. PMID 27802131.

- ↑ Hopfner KP, Karcher A, Shin DS, Craig L, Arthur LM, Carney JP, Tainer JA (2000). "Structural biology of Rad50 ATPase: ATP-driven conformational control in DNA double-strand break repair and the ABC-ATPase superfamily". Cell. 101 (7): 789–800. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80890-9. PMID 10892749.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Connelly JC, Kirkham LA, Leach DR (1998). "The SbcCD nuclease of Escherichia coli is a structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) family protein that cleaves hairpin DNA". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95 (14): 7969–7974. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.7969C. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.14.7969. PMID 9653124.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Michel-Marks E, Courcelle CT, Korolev S, Courcelle J (2010). "ATP binding, ATP hydrolysis, and protein dimerization are required for RecF to catalyze an early step in the processing and recovery of replication forks disrupted by DNA damage". J. Mol. Biol. 401 (4): 579–589. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2010.06.013. PMID 20558179.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Pellegrino S, Radzimanowski J, de Sanctis D, Boeri Erba E, McSweeney S, Timmins J (2012). "Structural and functional characterization of an SMC-like protein RecN: new insights into double-strand break repair". Structure. 20 (12): 2076–2089. doi:10.1016/j.str.2012.09.010. PMID 23085075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Yoshinaga M, Nakayama T, Inagaki Y (2022). "A novel structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC)-related protein family specific to Archaea". Front Microbiol. 13: 913088. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.913088. PMID 35992648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Herrmann U, Soppa J (2002). "Cell cycle-dependent expression of an essential SMC-like protein and dynamic chromosome localization in the archaeon Halobacterium salinarum". Mol Microbiol. 46 (4): 895–906. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03181.x. PMID 12406217.

- ↑ Takemata N, Samson RY, Bell SD (2019). "Physical and Functional Compartmentalization of Archaeal Chromosomes". Cell. 179 (1): 165–179.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.036. PMID 31539494.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Pilatowski-Herzing E, Samson RY, Takemata N, Badel C, Bohall PB, Bell SD (2025). "Capturing chromosome conformation in Crenarchaea". Mol Microbiol. 123 (2): 101–108. doi:10.1111/mmi.15245. PMID 38404013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Melby TE, Ciampaglio CN, Briscoe G, Erickson HP (1998). "The symmetrical structure of structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) and MukB proteins: long, antiparallel coiled coils, folded at a flexible hinge". J. Cell Biol. 142 (6): 1595–1604. doi:10.1083/jcb.142.6.1595. PMC 2141774. PMID 9744887.

- ↑ Anderson DE, Losada A, Erickson HP, Hirano T (2002). "Condensin and cohesin display different arm conformations with characteristic hinge angles". J. Cell Biol. 156 (6): 419–424. doi:10.1083/jcb.200111002. PMC 2173330. PMID 11815634.

- ↑ Haering CH, Löwe J, Hochwagen A, Nasmyth K (2002). "Molecular architecture of SMC proteins and the yeast cohesin complex". Mol. Cell. 9 (4): 773–788. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00515-4. PMID 11983169.

- ↑ Hirano M, Hirano T (2002). "Hinge-mediated dimerization of SMC protein is essential for its dynamic interaction with DNA". EMBO J. 21 (21): 5733–5744. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf575. PMC 131072. PMID 12411491.

- ↑ Ganji M, Shaltiel IA, Bisht S, Kim E, Kalichava A, Haering CH, Dekker C (2018). "Real-time imaging of DNA loop extrusion by condensin". Science. 360 (6384): 102–105. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..102G. doi:10.1126/science.aar7831. PMC 6329450. PMID 29472443.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Davidson IF, Bauer B, Goetz D, Tang W, Wutz G, Peters JM (2019). "DNA loop extrusion by human cohesin". Science. 366 (6471): 1338–1345. Bibcode:2019Sci...366.1338D. doi:10.1126/science.aaz3418. PMID 31753851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kim Y, Shi Z, Zhang H, Finkelstein IJ, Yu H (2019). "Human cohesin compacts DNA by loop extrusion". Science. 366 (6471): 1345–1349. Bibcode:2019Sci...366.1345K. doi:10.1126/science.aaz4475. PMC 7387118. PMID 31780627.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Pradhan B, Kanno T, Umeda Igarashi M, Loke MS, Baaske MD, Wong JSK, Jeppsson K, Björkegren C, Kim E (2023). "The Smc5/6 complex is a DNA loop-extruding motor". Nature. 616 (7958): 843–848. Bibcode:2023Natur.616..843P. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05963-3. PMID 37076626.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Oldenkamp R, Rowland BD (2022). "A walk through the SMC cycle: From catching DNAs to shaping the genome". Mol Cell. 82 (9): 1616–1630. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2022.04.006. PMID 35477004.

- ↑ Dekker C, Haering CH, Peters, JM, Rowland, BD (2023). "How do molecular motors fold the genome?". Science. 382 (6671): 646–648. Bibcode:2023Sci...382..646D. doi:10.1126/science.adi8308. PMID 37943927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Report on the second international meeting on SMC proteins

- ↑ EMBO Workshop 2019

- ↑ NIG & RIKEN International Symposium 2024