Aqua Tofana

Aqua Tofana (also known as Acqua Toffana and Aqua Tufania and Manna di San Nicola) was a strong, arsenic-based poison created in Sicily around 1630[1] that was reputedly widely used in Palermo, Naples,[2] Perugia, and Rome, Italy. The name Aqua Tofana has eveolved to refer to a category of slow poisons that are incredibly deadly but largely indetectable, just as Aqua Tofana was. These slow posions may have been used frequently throughout the 19th century.[3] It has been associated with Giulia Tofana, or Tofania, a woman from Palermo, purportedly the leader of a ring of six poisoners in Rome, who sold Aqua Tofana to would-be murderers.

Original creation

The first recorded mention of Aqua Tofana is from 1632–33[4][1] when it was used by two women, Francesca la Sarda and Teofania di Adamo, to poison their victims. It may have been invented by, and named after, Teofania.[1] She was executed for her crimes, but several women associated with her including Giulia Tofana (who may have been her daughter) and Gironima Spana moved on to Rome and continued manufacturing and distributing the poison.[1] Once in Rome, the women may have acquired the main ingredient, arsenic, from Father Girolamo of Sant'Agnese in Agone. Father Girolamo had access of this poison by way of his brother, who was an apothecary.

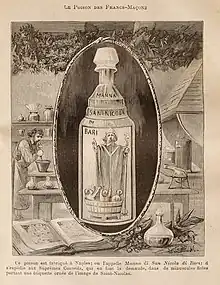

Tofana and her circle of trusted women camouflaged Aqua Tofana was camouflagedin a bottle labeled "Manna di San Nicolas" complete with a picture of the saint. Manna di San Nicolas was cosmetic and healing oil said to heal blemishes. This oil was said to be extracted from San Nicolas's bones in a church located in Bari, Italy. Over 600 victims[2] are alleged to have died from this poison, mostly husbands.

Aqua Tofana was camouflagedin in bottles wih the 'tradename' "Manna di San Nicola" ("Manna of St. Nicholas of Bari"), a marketing device intended to divert the authorities, giving the poison an apperence of cosmetic and a devotional object in vials that included a picture of St. Nicholas. Over 600 victims[2] are alleged to have died from this poison, mostly husbands.

Between 1666 and 1676, the Marchioness de Brinvilliers poisoned her father and two brothers, amongst others, and she was executed on July 16, 1676.[5]

Ingredients

The active ingredients of the mixture are known, but not how they were blended. Aqua Tofana contained mostly arsenic and lead, and possibly belladonna. It was a colorless, tasteless liquid and therefore easily mixed with water or wine to be served during meals.

Symptoms

Poisoning by Aqua Tofana could go unnoticed, as the substance is clear and has no taste. Its tasteless properties signify that it was made with a deliberate attempt to hide the potent metallic taste of arsenic, Aqua Tofana's key ingredient.[6] It is slow-acting, with symptoms resembling progressive disease or other natural causes. The symptoms seen are similar to the effects of arsenic poisoning. Those poisoned by Aqua Tofana reported several symptoms. The first small dosage would produce cold-like symptoms. The victim was very ill by the third dose; symptoms included vomiting, dehydration, diarrhea, and a burning sensation in the victim's throat and stomach. The fourth dose would kill the victim. As it was slow acting, it allowed victims time to prepare for their death, including writing a will and repenting. The antidote often given was vinegar and lemon juice.[7][8]

Legend about Mozart

The legend that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) was poisoned using Aqua Tofana[9] is completely unsubstantiated, even though it was Mozart himself who started this rumor.[10]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Philip Wexler, Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Elsevier Science - 2017, pages 63-64

- 1 2 3 Stuart, David C. (2004). Dangerous Garden. Harvard University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780674011045.

La Toffana....aqua Toffana

- ↑ Dash, Mike. "Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance". Science Direct. Academic Press. Retrieved 21 February 2025.

- ↑ Dash, Mike. "Aqua Tofana". academia.edu. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ↑ Vincent, Benjamin (1863). Dictionary of Dates. London: Edward Moxon & Co.

- ↑ Dash, Mike. "Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance". Science Direct. Academic Press. Retrieved 21 February 2025.

- ↑ Dash, Mike (2017). "Chapter 6 - Aqua Tofana". In Wexler, Philip (ed.). Toxicology in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Academic Press. pp. 63–69. ISBN 9780128095546.

- ↑ "Aqua Tofana: slow-poisoning and husband-killing in 17th century Italy". A Blast From The Past. 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Chorley, Henry Fothergill. 1854. Modern German Music: Recollections and Criticisms. London: Smith, Elder & Co., p. 193.

- ↑ Robbins Landon, H. C., 1791: Mozart's Last Year, Schirmer Books, New York (1988), pp. 148 ff.

External links

- Definition at thefreedictionary.com

- Definition at infoplease.com