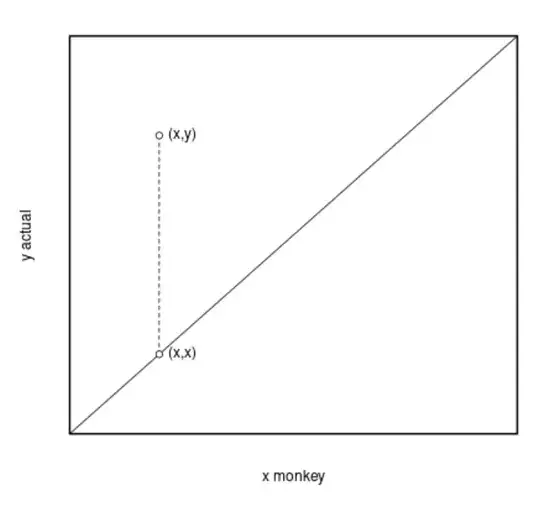

Let's assume I have actual numbers (randomly generated) between 1 and 1000. Let's further assume, my prediction model tries to predict the actual numbers. My "forecasting" model is a monkey that true-randomly presses buttons between 1 and 1000. Essentially, it is the same function which is used to generate the actual numbers. I just put two sets of randomly generated numbers next to each other and calculate their difference ("error").

If I follow this logic and calculate the mean absolute error of the monkey model and normalize it with the actual numbers, the MAE will be around 66%. Just to confirm, the formula to calculate the MAE is: SUM(ABS(Actual-Forecast))/SUM(Actual).

You can create this model easily in Excel.

What is an intuitive explanation for why I get exactly a value of 66.666% the more numbers I generate? My understanding is, that on average I predict 66% of an actual figure wrong.