I have a dataset $D$ of binary values, with length $|D|$. There is some unknown $d \in \left[1,2,\ldots,|D|\right]$ (usually, $d$ will be somewhere in the middle) such that, for any $i<d$, $D_i$ comes from a Bernoulli distribution with success probability $Q_1$, and for $i \geq d$, $D_i$ comes from a Bernoulli distribution with success probability $Q_2$. For the purposes of this question, assume $0 < Q_1 < 1/2 < Q_2 < 1$.

If I use a sliding window of size $k \ll |D|$ and take the sum within the window, I'll find that when the window is only on values with index $i < d$, the sum will hover around $kQ_1$, and when the window is only on values with index $i \geq d$, the sum will hover around $kQ_2$. As the window slides through indices around $i \approx d$, the sum will jump from $kQ_1$ to $kQ_2$, marking a change point. (I'm definitely open to other methods!)

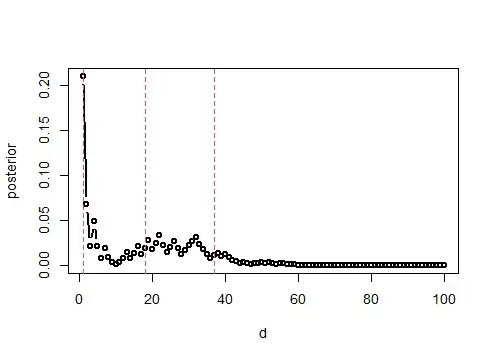

I want to use an algorithm like step detection to detect $d$, but I don't want to appeal to heuristics. I want to find a way to get within some bound of $d$ with at least a certain probability. This problem is easier than the general change point detection problem because there is exactly one change point, and I know the value of the mean before and after $d$ (so I know the magnitude of the change). Is this a known problem? I'm thinking that we can bound the probability of being within some multiple of $k$ from $d$, and that the calculation would involve calculating the probability that you get a sum of $kQ_1$ when the binomial process has $p = Q_2$ and vice versa.

This problem is also similar to this question, though there they also don't seem to get any complexity results.