It's apparent that you have a good grasp on the business problem. This response is to suggest alternative ways to think about it.

One thing you haven't mentioned is the industry for which these models are being built. Knowing this would help set expectations about how any model is likely to perform. For example, in direct marketing, strategists expect a large percentage of customers to be one time shoppers. So, given a purchase in one year the likelihood of a purchase in subsequent years is extremely small. In health insurance, actuaries expect several things: most members will never file a claim, the unhealthiest ~5% of members are likely to drive 20% (or more) of claims, claims are extremely fat tailed, and so on.

Insurance actuaries have developed a boatload of metrics, some of which may have relevance for your project, e.g., https://guidingmetrics.com/content/insurance-industrys-18-most-critical-metrics/

That said, your current approach reminds me of a problem once presented to me. I was given a composite metric of claims severity (cost) divided by frequency (how many filed). This metric was this company's unique definition of a loss ratio. The objective was to build a predictive model with this composite as the target. I was not given access to the input components, just the composite.

The problem was that this composite contained some huge outliers, both large and miniscule, e.g., members with a single hugely expensive claim on the one hand and others with many low cost claims on the other.

Modeling the composite proved to be extremely difficult. If I had had the components it would have been much easier. I would have built two models and combined them later to form the loss ratio.

The point is that, if it's possible, decomposing your profitability metric into its component parts, modeling those and combining them later to create profitability might be a more workable solution. For example, your metric includes returns and, therefore, is downstream from actual purchases. As a rule, sales revenue is a less reliable metric of customer behavior than unit sales, and so on.

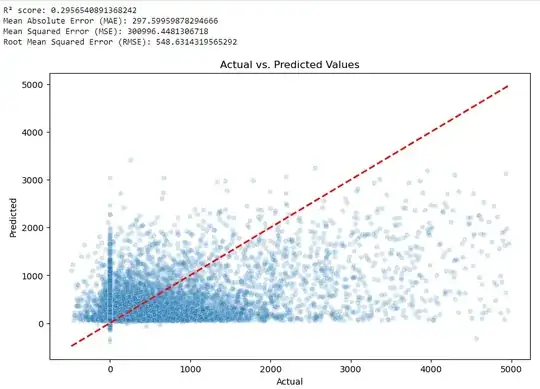

The next suggestion is based on your chart showing a distribution of customer profitability. It's apparent that profitability is extremely fat tailed. Given that, traditional models based on normally distributed data can be expected to perform poorly since, by definition, they can't predict the tails.

Alternative approaches include:

Hope this helps.