There are infinitely many distributions we could create,

Indeed there are.

but we rely on picking one with a 'name' for our analysis.

It could well be more common to use the beta as a prior than not, but it is not at all a requirement, and you do definitely see people do other things. For one example, see the variety of priors on the intercept in a logistic regression, which - holding the other coefficients at 0 - imply a non-beta prior on $p$ unless the intercept-prior was generalized logistic (specifically, type IV in the Wikipedia page on the generalized logistic).

We can use whatever prior we choose. A conjugate prior is a common choice in this case but its not something that many people will necessarily do.

If we want a specific prior there's nothing stopping us, aside from some additional effort.

That said, (albeit partially repeating a point from your question), a beta prior is particularly convenient in a couple of important senses:

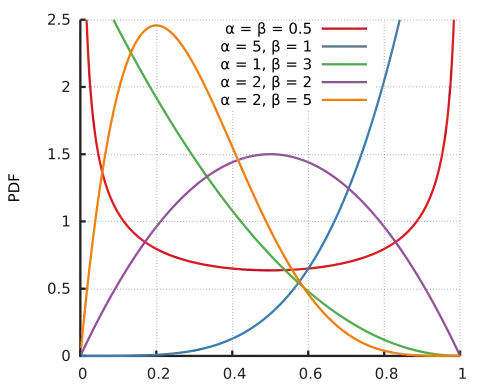

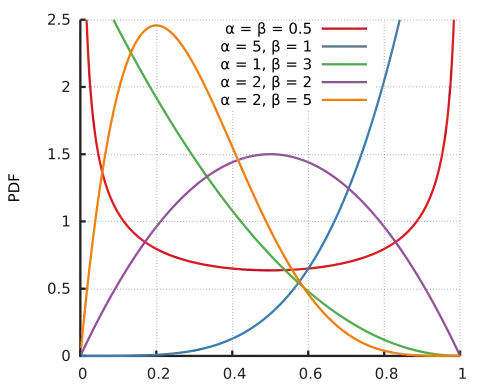

It has a variety of possible shapes, left skew, right skew, symmetric, hill-shaped, J-shaped, bimodal, all with the right support. You can choose its mean and spread fairly readily, which is handy.

If you're trying to elicit a prior, having a moderately flexible set of options based on a limited set of parameters can be convenient. Completely free (infinite) choice can make it harder to pick than a more constrained choice, where the structure can move the person whose prior we're trying to get at from analysis paralysis to making a reasonable choice more readily.

It's relatively easy to look at a set of images of a variety of distributions and start saying things like "well, I want the mode about where that one is, maybe left a bit, but not so concentrated around that value". Rather than floating in an unmarked sea of possibility, we can lay out some easy signposts -- and if the family doesn't offer quite what we're after, we will at least have thought about in what specific ways we want to vary our prior away from the beta, which again helps guide our thinking.

(image by Wikipedia user Horas, placed in the public domain)

As an added bonus its at least fairly easy to work with on its own right.

It's the conjugate distribution of the binomial, as you note. This means if your prior is beta, so is the posterior. That's a very handy property. It's especially useful if you have an online algorithm where you're updating your posterior with each new observation. This can be a life saver in time-critical applications.

Even if no simple distribution were sufficient to cover your needs for a prior, mixtures of betas and piecewise betas are also potential options with much greater flexibility and they result in mixture or piecewise beta posteriors respectively. That's also quite handy in some cases.

Here's an example that's not particularly close to any beta density, but might be a plausible prior that could reasonably represent something a person may choose. It's a simple mixture of two beta densities.

Consequently in a variety of situations, especially if we had no particular reason to choose something else, we might choose to start with a beta or something based off a beta.

Many people use hyper priors, putting distributions on the choice of parameter in the prior. This makes it possible to partly account for the fact that our prior is itself a very uncertain thing. This approach is (again) a form of mixture prior.

On the matter of choosing priors, outside the issues of eliciting priors- especially going from some broad but somewhat vague belief to a specific prior, it's very much a matter of circumstances. We're rarely in a position of even have a criterion for 'best' when it comes to priors, more usually we have a set of criteria and some vague ideas about our prior knowledge/belief, and the choice is typically made to balance the knowledge have and whatever other criteria we might seek to apply. This is a broad question that applies in almost any Bayesian analysis. There are many posts on site that relate to aspects of prior choice, but you could well fill a book with details. It might help to ask a more focused question on that aspect.

Summary: the premise of the question - that we rely on choosing a beta prior is mistaken. We are free to use it or not, as suits our needs. There can be good reason to use it, or good reasons to use something else.