If $X$ has multiple values, then for any increasing function $f(X)$, the correlation between $X$ and $f(X)$ will always be positive.

So, there is no transform that you can apply to $X$ (like subtracting the mean) such that for the transformed variable $X'$ the correlation between $X'$ and $f(X')$ becomes zero, except a transformation with a multiplication by zero.

(The multiplication by zero will make that there are no multiple values anymore)

If the correlation is zero then the covariance is zero.

This covariance can be written as

$$\begin{array}{}

\text{Cov}[X,f(X)] &=&

\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-\mu_{x}) (f(x_i)-\mu_{f(x)})

\end{array}$$

And shifting up or down the second term with a constant $a$ will not change the sum

$$\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-\mu_{x}) (f(x_i)-\mu_{f(x)}) = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n (x_i-\mu_{x}) (f(x_i)-\mu_{f(x)}-a)$$

Now, if $f(X)$ is an increasing function of $X$, then we can choose the constant $$a = f(\mu_x)-\mu_{f(x)}$$ such that $$\text{sign}(x_i-\mu_{x}) = \text{sign}(f(x_i)-\mu_{f(x)}-a)$$ and the terms in the sum will be a sum of only non-negative terms

$$\text{sign}\left((x_i-\mu_{x})\cdot(f(x_i)-\mu_{f(x)}-a)\right) = \begin{cases} 0 &\quad \text{if $x_i = \mu_{x}$} \\

1& \quad\text{else}\end{cases}$$

Therefore, the summation used to compute the covariance, can be written as a sum of terms that are all non-negative, and the final sum will be non-negative, where equality to zero only occurs when for all values we have $x_i = \mu_x$, ie when all values are the same.

Example

In the comments you asked

Can you explain why $\text{sign}(x_i-\mu_{x}) = \text{sign}(f(x_i)-f(\mu_{x}))

$

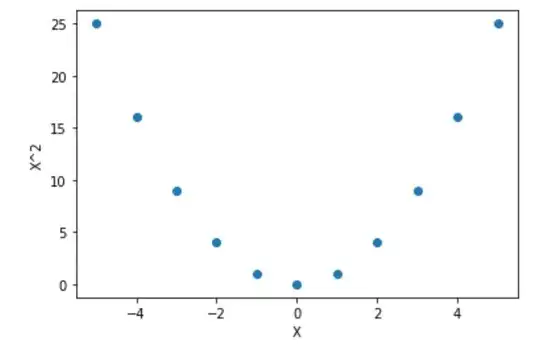

possibly the following illustration may help

To compute the covariance you multiply for each point the values on the horizontal axis with the values on the vertical axis (and take the average).

The difference between the left and right image is only that we moved the points up such that the function (defining the points) crosses the origin. This shift leaves the result from the computation unchanged (the constant multiplied with the $x_i-\mu_x$ will be on average zero), but now all the terms will be a product of two negative numbers or two positive numbers and we can clearly see that the end result needs to be positive.

This shift can be made for any increasing function, no matter what the underlying X values are, with the only exception when the points are all the same value.