The reconstructed dataset using a subset of principal components is an orthogonal projection: a mathematical generalization of the process of rendering a 3D scene as an image.

This famous Escher print projects a regular array of shapes into fewer dimensions. The locations of the shapes in the paper is no longer regular (it is not a lattice).

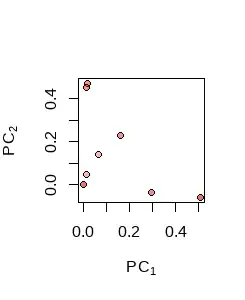

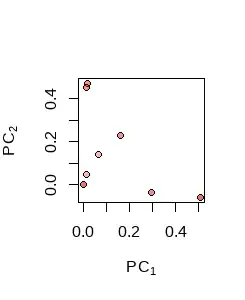

Binary data in $n$ dimensions, whose values are limited to $0$ and $1,$ are necessarily located on the integer lattice (of vectors with integral coordinates). But when projected, even into a space of just one dimension less (as in the Escher print), they will not necessarily appear lattice-like. Here, for instance, is the projection of 16 binary vectors in $32$ dimensions onto the space spanned by their first two principal components:

(There is some overlap in the projections, evidenced by the stronger coloration in the overlapping points, yielding only 8 distinct points.)

It therefore is unrealistic to hope either that such a "partial reconstruction" will have all binary coordinates (which would cause all the points to fall on the integer lattice) or even that rounded versions would correctly reproduce the original data.

To demonstrate this, here are the original dataset, its reconstruction based on the top five principal components, and the rounded version of that reconstruction. All are plotted as images in which each column represents a vector.

(This PCA centered all the columns but did not rescale them.) This reconstruction accounts for 87% of the variance. All the variance is accounted for by the top seven PCs, indicating this reconstruction is a projection from a space that is inherently of seven dimensions into a space of five dimensions.

You can see that many of the reconstructed coordinates are close to $0$ (lightest color) or $1$ (darkest color), but not all are. At the right, you will notice the rounded reconstruction looks substantially like the original, but not quite. About 1.2% of the coordinates flipped from $0$ to $1$ and another 2.0% of them flipped from $1$ to $0.$

Here, to show the details of the calculations, is the R code used to generate this example.

#

# Generate binary data.

#

set.seed(17)

p <- 16 # Number of observations

n <- 32 # Dimension of the vectors (cannot be less than `p`)

kmax <- 3 # Roughly, determines the rank of the matrix

A <- matrix(sample(0:1, p * kmax, replace = TRUE), ncol = p)

X <- (matrix(sample(0:1, n * kmax, replace = TRUE), n) %*% A) %% 2

#

# Perform PCA.

#

obj <- princomp(X)

screeplot(obj) # Charts contributions from the highest PCs

with(obj, signif(cumsum(sdev^2)[1:10] / sum(sdev^2), 3)) # Their contributions

#

# Reconstruct the data from a specified number of PCs.

#

k <- 5 # PCs used for reconstruction

X. <- with(obj,

t(zapsmall(loadings[, 1:k, drop = FALSE] %*% t(scores)[1:k, , drop = FALSE]

+ center)))

#

# Display `X.`, `X`, and its rounded version as images.

#

par(mfrow = c(1,3))

i <- list(Reconstructed = X., Original = X, Rounded = round(X.))

for (s in names(i)) {

image(i[[s]], bty = "n", xaxt = "n", yaxt = "n", main = s)

}

par(mfrow = c(1,1))

#

# Evaluate the differences between the original data and the rounded reconstruction.

#

table(X - round(X.)) / length(X)

with(obj, plot(loadings[, 1:2], pch = 21, bg = hsv(0.02, 1, 1, 0.3),

xlab = expression(PC[1]), ylab = expression(PC[2])))

Or is 5% of unrepresented variance enough to swing the value of some cells ? (for example, 0.85 would become 1 with 5 PCs, but if I reconstruct the data using all the PCs could it actually be a 0 ?)

– vdc Jul 17 '23 at 21:16