My case, as it seems to me, should be quite common, yet I cannot find any information.

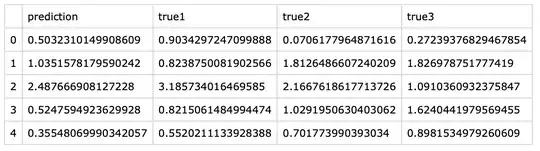

The situation is as follows: there is a regression model, and for each predicted value, there are multiple true values. For example:

What methods are there to evaluate the predictions?

Of course, I can evaluate predictions relative to the median value or the mean.

For example, AE would be: $$ AE_i = \mid\hat{y_i} - \frac{1}{3}({y_i}_1 + {y_i}_2 + {y_i}_3)\mid = \mid\hat{y_i} - \bar{y_i}\mid $$

where $\hat{y_i}$ is the i-th prediction, $\bar{y_i}$ is the mean of true values ${y_i}_1, {y_i}_2, {y_i}_3$.

However, errors relative to the mean or median do not reflect the variance of the true values. My idea is that if the prediction falls inside the range of the true values, the error should be significantly smaller compared to the error relative to the mean, or even equal to zero.

I can think of several metrics.

- Percent of predictions falling inside the corresponding true value range. This metric, however, does not reflect how bad are predictions which do not fall inside the ranges.

- "Relative absolute error". The sum of distances between the prediction and real values devided by the sum of distances between the mean and the real values. $$ e_i = \frac{\sum_j{\mid \hat{y_i} - {y_i}_j \mid}}{\sum_j{\mid{y_i}_j - \bar{y_i} \mid}} $$ where $\bar{y_i}$ is the mean of real values ${y_i}_1, {y_i}_2, {y_i}_3$.

- Absolute error relative to quantiles. For example, to evaluate predictions relative to quantiles 0.1 and 0.9:

$$ E = {Q_i}_{0.1} - \hat{y_i}, \quad \text{if }\enspace \hat{y_i} < {Q_i}_{0.1} \\ E = 0, \quad \text{if }\enspace {Q_i}_{0.1} \le \hat{y_i} \le {Q_i}_{0.9} \\ E = \hat{y_i} - {Q_i}_{0.9} , \quad \text{if }\enspace {Q_i}_{0.9} < \hat{y_i} $$

where ${Q_i}_{0.1}$ and ${Q_i}_{0.9}$ are the corresponding quantiles of the true values ${y_i}_1, {y_i}_2, {y_i}_3, ...$

In my case, I have 10 to 90 true values for each prediction. Their distribution is not symmetrical (otherwise, errors relative to the median could be compared to the spread or range width of the true values).

Do you think any of the errors 1.-3. could be useful? What are the more common ways to evaluate predictions in such cases?

Some specifics of my case. I want to predict the time of computation of a piece of code. The computation time naturally fluctuates, however, mainly in the direction of larger values (longer computation times). It also has outliers. Since the code execution times vary, I make multiple measurements. Execution time depends on the hardware and some other parameters. I conduct similar sets of measurements on several machines, also for different data sizes (varying one parameter that changes the size of the data used in computations and impacts execution time) and for different code pieces (defined by a large set of parameters). Thus, for each combination of a machine, a particular piece of code and a data size, I have multiple execution time measurements. For different machines, codes and data sizes, the execution times magnitude and spread (variance) are also different. To mitigate uncertainty, I conduct more measurements when the execution time variation is large.

I want to build a prediction model, that for the given machine, piece of code and data size, would predict the execution time. To evaluate my model predictions, I want a metric that would not only tell how far/close to the median time the predictions are, but also consider the spread of the real values (measured execution times) because if the spread is large, predictions farther away from the median still can be considered as good predictions.