What is actually required is conditional independence of the response variable. Conditional on the regressors, that is. A Poisson regression model - for independent data - is no different from an ordinary least squares model in this assumption except that the OLS conveniently expresses the random error as a separate parameter.

In a Poisson regression model, the specific form of the conditional response is debatable due to disagreements in the fields of probability and statistics. One popular option would be $Y/\hat{Y}$, which are still random variables albeit not exactly Poisson distributed - the value is considered an ancillary statistic like a residual, which does not depend on the estimated model parameters. An interesting thing to observe here is that, if the linear model is misspecified (such as omitted variable bias), this may induce a kind of "dependence" on the residue of the fitted component of the model that is not correctly captured.

Independence has a very specific probabilistic meaning, and most attempts to diagnose dependence with diagnostic tests are futile. This is mostly complicated by the important mathfact that independence implies covariance is zero, but zero covariance does not imply independence.

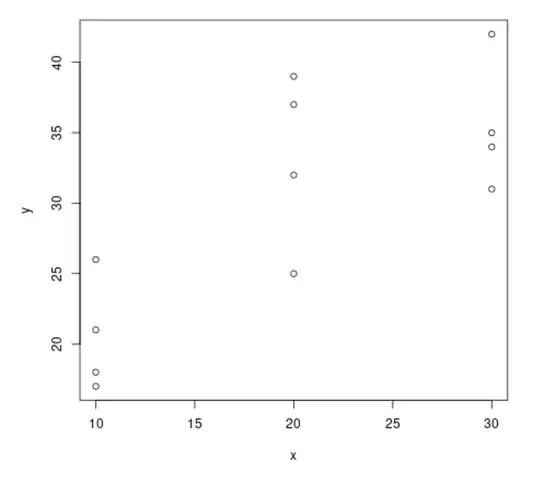

Poisson regression and OLS are special cases of "generalized linear models" or GLMs so we can conveniently deal with the independence of observations in GLMs. The classic OLS residual plot, which we use to detect heteroscedasticity, is effective to visualize a covariance structure, but additional assumptions are needed to declare independence. In a GLM such a Poisson, a non-trivial mean-variance relationship is an expected feature of the model; a standard residual plot would be useless. So we rather consider the Pearson residuals versus fitted as a diagnostic test. In R, a simple poisson GLM(x <- seq(-3, 3, by=0.1); y<-rpois(length(x), exp(-3 + x)); f <- glm(y ~ x, family=poisson). The resulting graph shows a tapering curve of residuals and, arguably a funnel shape, with a LOESS smoother showing a mostly constant and 0-expectation mean residual trend.

As an example, we may describe the distribution of the $x$ as the design of the study. While many examples here and in textbooks deal with $X$ as random, that's merely a convenience and not that reflective of reality. The design of experiment is to assess viral load of infected mouse models treated with antivirals at a sequence of dose concentrations, say, control, $X = (0 \text{ control}, 10, 50, 200, 1,000,$ and $5,000)$ mg/kg. For an effective ART, the sequence of viral loads is expected to be descending because of a dose-response relationship. The outcome might look $Y = (10^5, 10^5, 10^4, 10^3, LLOD, LLOD)$. This response vector is not unconditionally independent, there is a strong "autoregressive" trend induced by the design. Trivially, when the fitted effect is estimated through the regressions, the conditional response is completely mutually independent.

A more involved but real life example is detailed in Agresti's categorical data analysis second edition in Chapter 3 covering poisson regression. This deals with the issue of estimating the number "satellite crabs" in a horseshoe crab nest, a sort of interesting polyamory. Data analyses can be found here.