Suppose we have a set A , we split into multiple disjoint subsets ai We only have access to the ai sets , is there a way to compute the ECDF for the set A without looking at it ? If for example we have ECDFi on ai and we average them , do we have guaranteed convergence ? We can not just combine all the subsamples for memory issues , the only thing we can do is compute the ECDF for each subsample so instead of k samples for the subset ai we will have 100 values ,(ECDF evaluated at 0% 1% .. 100%) which reduces drastically the memory needed , a subset can have a size of 1000000 , we compress everything into 100 digits Now given these 100 digits for each subsets how to infer the ECDF for the A which is the union of the ais

By average here I mean vertically (if we stack the ECDFs vertically) FA(0%) would be avg(Fai(0%) and so on for each X%

I actually did some simulations to find out and it seems that it works

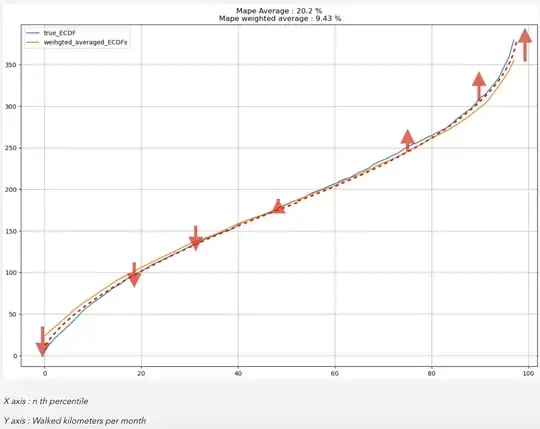

I’ve chosen this metric (mape) because in case of the ECDF , the 100% percentile is by definition the largest , therefore an error in the 100% percentile would inflate the whole error , even though it is an error in only one point of the function . For example an error on the 100% percentile of approx: 400 vs true : 800 , we want it to be treated the same way as an error of approx : 40 vs true : 80 in the 40% percentile , because we want the function to converge in each point , we may even tolerate divergence in the 100% percentile.

- avg_mape is the average error when we only averaged the ECDFs

- weighted_avg_mape is the average error when we averaged using weights that are proportional to the size of the subset ai the ECDFs

I tried different underlying distributions with different parameters (sigma , mu , lambda ..) The imbalance here refers to how uneven the partitioning is doen (A to ais) you can see it as inversely proportional to the entropy , with max entropy all ratios are even and lowest entropy something like 90% , 1 % 9 %

But we know already that the average will dilute the 100% percentile (we average the true 100% with inferior factors ) and will inflate the minimum . Nearby percentiles will have similar behavior as well , as shown in this figure :

What we would like to do is to bend the curve a little from the extremities (up in the right and down in the left )

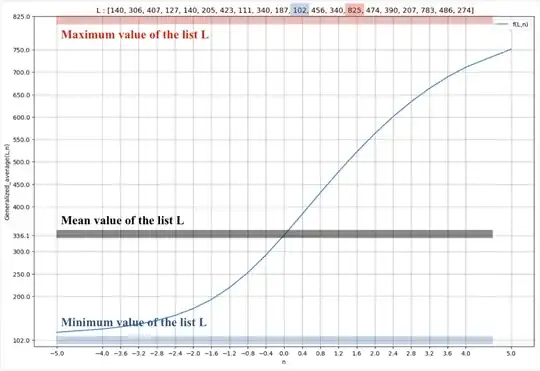

I came up with the following function to do it (kind of a generalized formula for the average ) :

$$F( L , n) = \sum (li^{n+1})/\sum (li^n)$$

L : List of positive numbers

if n goes to ∞ F returns the maximum of L if n goes to -∞ F returns the minimum of L if n = 0 F returns the average of the list L

Here is how the function acts on a list while varying the n

We can of course use the weights coming from the size of subsets ai combined

And now instead of using a weighted average vertically we will use F(Lx% , n) L x% is the list containing all the Fai(10%) for example n would tend toward infinity if X is 100 toward -∞ if X is 0% 0 if X is 50% and for the rest of the values we will vary n the n continuously from -∞ to +∞

Here is an example of the result after bending the extremities

Following is the evaluation of different approaches :

Now the problem is that I can not come with a consistent proof of the convergence of the approach even-though it sounds intuitive ? And I really have no Idea how accurate all of this is ?