I am taking a course in Statistics and our prof showed us a real survey that was recently in the news. In a country with a population of roughly 30-40 million people, only 1000 people were asked about their opinion on a controversial political question (e.g. should more money be invested in healthcare?). The results indicated that "yes" - and the headline of the news article was "majority of citizens support increasing investments in healthcare".

Some information about the methodology used in the survey was provided - allegedly, this survey took into consideration random sampling proportional to key demographics identified within the census. As a result, the opinion of only 0.002% of the country's population was considered sufficient to represent the entire country's opinion on this matter. –

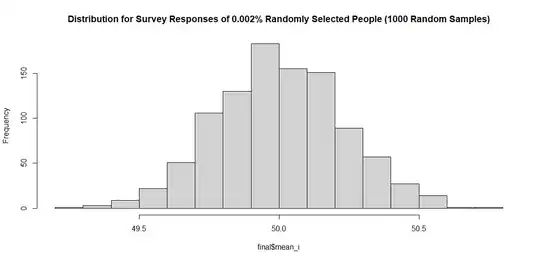

I personally find this application of statistics to be very incredible! Suppose the "opinions" of the population have a normal distribution - an estimate generated from a random sample of 0.002% of the country gets very close to the actual average opinion (provided the average opinion is actually known)! For example, suppose we ask people "how much should healthcare spending be increased relative to the current spending (in percentage)?" (e.g. 14% more, 39% more, etc.). Suppose we assume that the response to this question has a normal distribution with a specific mean and variance (e.g. average person thinks the country should invest 50% more in healthcare) - the following simulation shows what would happen if this question was asked to 0.002% of the population (using R):

set.seed(123)

my_data = data.frame(id = 1:1000000, percent_increase_in_health_care = rnorm(1000000,50, 10))

results = list()

for (i in 1:1000)

{

sample_i = my_data[sample(nrow(my_data), 2000), ]

mean_i = mean(sample_i$percent_increase_in_health_care)

results[[i]] = data.frame(i, mean_i)

}

> mean(final$mean_i)final = do.call(rbind.data.frame, results)

[1] 50.00377

plot(hist(final$mean_i, main = "Distribution for Survey Responses of 0.002% Randomly Selected People (1000 Random Samples)"))

As we see, even when such a tiny percent of the population was asked for the opinion - the average opinion from this tiny sample is pretty close to the actual average opinion of the population!

I was personally curious in seeing what happens if the opinions of the country are not normally distributed and a similar percentage of the country are asked for their opinions - would the same accuracy still hold? And does this accuracy of this estimate become worse the "further" you move away from a normal distribution? (e.g. gamma, weibull, etc.)

As an example - imagine a country in which half the people think healthcare spending should be nearly doubled (i.e. 100% increase) and half the people think that healthcare spending should remain at roughly what it is (i.e. 0% increase):

set.seed(123)

my_data_1 = data.frame(id = 1:500000, percent_increase_in_health_care = rnorm(500000,5, 1))

my_data_2 = data.frame(id = 500001:1000000, percent_increase_in_health_care = rnorm(500000,90, 5))

my_data = rbind(my_data_1, my_data_2)

results = list()

for (i in 1:1000)

{

sample_i = my_data[sample(nrow(my_data), 2000), ]

mean_i = mean(sample_i$percent_increase_in_health_care)

results[[i]] = data.frame(i, mean_i)

}

final = do.call(rbind.data.frame, results)

mean(final$mean_i)

[1] 47.56409

plot(hist(final$mean_i, main = "Distribution for Survey Responses of 0.002% Randomly Selected People (1000 Random Samples)"))

In the end, is this true? Regardless of the underlying distribution of the response variable (e.g. percent increase in healthcare spending) - if a proportional sample is chosen, on average and over many experiments, the mean response will reflect the true mean response of the population?