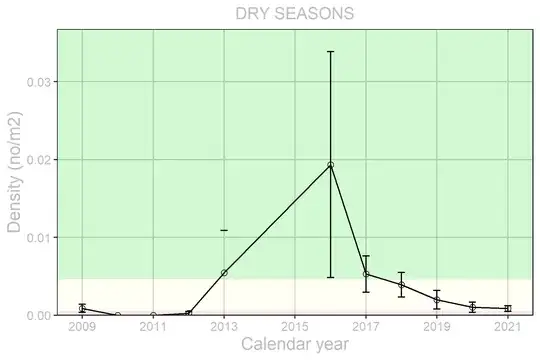

I've been trying to figure out how to test (in R) if there are significant differences between the group means of my data because it seems to violate the assumptions of tests that do this (ANOVA, Kruskal-Wallis). The obvious problem I have is that my data have large differences in group variability and relatively small sample sizes by group (11 to 36 observations).

> dput(df_count)

structure(list(Year = c(2018, 2019, 2020, 2017, 2010, 2011, 2013,

2016, 2021, 2009, 2012), n = c(36L, 34L, 25L, 24L, 12L, 12L,

12L, 12L, 12L, 11L, 11L)), row.names = c(NA, -11L), class = c("tbl_df",

"tbl", "data.frame"))

I've read I can't run a Kruskal-Wallis test if I don't have homogeneity of variance or small sample sizes like these. One possible work around I got from a colleague would be to convert my density values to presence absence (anything about 0 gets turned into a 1) and do a chi-square test on the proportion of 0's to 1's, but we weren't sure if that was a good solution. I'd also like to do a pairwise comparison, but again wasn't sure what problem would arise given the properties of this dataset.

My data:

> dput(df)

structure(list(Year = c(2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018,

2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020,

2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019,

2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018,

2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2019, 2019, 2019,

2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2013, 2013, 2013,

2013, 2013, 2013, 2013, 2013, 2013, 2013, 2013, 2013, 2009, 2009,

2009, 2009, 2009, 2009, 2009, 2009, 2009, 2009, 2009, 2010, 2010,

2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2010, 2011,

2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011, 2011,

2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012, 2012,

2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016, 2016,

2016, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017,

2017, 2017, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018, 2018,

2018, 2018, 2018, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2019,

2019, 2019, 2019, 2019, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020,

2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2020, 2021, 2021, 2021, 2021, 2021, 2021,

2021, 2021, 2021, 2021, 2021, 2021, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017,

2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017, 2017), den = c(0.010339884588578,

0.00455728179952938, 0.00343679685937641, 0, 0, 0, 0.0026099691969192,

0.00261493942751616, 0, 0.00758841788700932, 0.00261098669259391,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.00258166076347894, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.00511179097342, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0.0344957485650341, 0, 0.00260181030586538, 0, 0, 0, 0.0090545203588682,

0, 0.00264281685601483, 0, 0.0378316032295272, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0654230184885466, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.00183150183150183,

0, 0.00535045478865704, 0.00260213374967473, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.00273945867001107, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0093124763796496,

0, 0.0104115475163763, 0.176865881398321, 0, 0.0168260157921274,

0.00986181407592425, 0.0031893056137876, 0.0254639674849916,

0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0211521212726769, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.00516893200484304,

0, 0, 0.0104424761130064, 0, 0, 0, 0.0421221519735819, 0, 0.00252790953920362,

0.0206951796482847, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,

0, 0.00777067045723764, 0.0104825822946628, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.0129942159892243,

0, 0, 0, 0.0103953727913794, 0, 0, 0.00259452618256605, 0, 0,

0, 0, 0.00260317460317461, 0, 0, 0, 0.00260752047062565, 0, 0.00259452618256605,

0.0026038446052897, 0.0226762329646423, 0, 0.00252708407882677,

0, 0.00548065139740094, 0, 0, 0, 0.0494424158277803, 0, 0.00748566757311657

)), row.names = c(NA, -201L), class = c("tbl_df", "tbl", "data.frame"

))