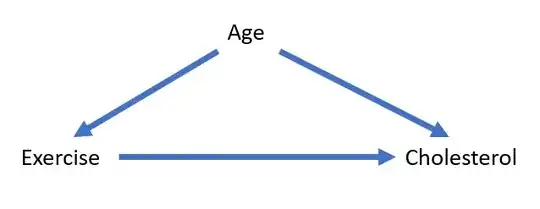

Suppose the DAG below is the true, complete, DAG for the effect of $Exercise$ on $Cholesterol$. $Exercise$ lowers $Cholesterol$; $Age$ causes people to $Exercise$ more; $Age$ causes $Cholesterol$ to increase. Now suppose that we are not interested in causal effects; we are, instead, building a predictive model of $Cholesterol$ and we do not have access to the $Age$ variable/any proxies of the $Age$ variable/any variables that are ancestors of $Age$.

Without $Age$ in the picture, we notice that $Exercise$ and $Cholesterol$ are positively correlated. This strikes us as counterintuitive because we know that $Exercise$ decreases $Cholesterol$; if we had $Age$ to control for, we'd see that for each $Age$ group $Exercise$ and $Cholesterol$ are negatively correlated.

Given the setup (we do not have access to $Age$/any proxies of $Age$/any variables that are ancestors of $Age$), if I am not mistaken, no matter what predictors we include in a predictive model of $Cholesterol$, the coefficient on $Exercise$ will always be positive (which doesn't make sense to us given our knowledge of the direct causal effect of $Exercise$ on $Cholesterol$).

Is there any sense in which because of the counter-intuitive sign on $Exercise$, a predictive model that includes $Exercise$ is flawed or we'd care less about estimating that coefficient with precision? Now let's throw away the confines of this contrived example: In the real world, can we have any reasonable expectation about what the signs of the predictors in a parametric predictive model would be?

Credits: In this post, I have repurposed an excellent example from Judea Pearl' book "Causal Inference in Statistics".