Because the correlation matrix must be positive semidefinite, then as shown at https://stats.stackexchange.com/a/5753/919 the three correlations $\tau=\rho_{AB},$ $\sigma=\rho_{AC},$ and $\rho=\rho_{BC}$ must satisfy the inequality

$$1 + 2(\rho\sigma)\tau - (\rho^2 + \sigma^2 + \tau^2) \ge 0\tag{*}$$

and, of course, all three values must be in the range $[-1,1].$

The question asks how to maximimize and minimize $\rho\sigma,$ given a value of $\tau$ and the constraint $(*).$ The following solution is elementary. Alternatively, it can be derived using Lagrange multipliers.

Setting $\phi = (\rho+\sigma)/2$ and $\delta = \rho-\phi$ (whence $\sigma-\phi = -\delta$) we find, with easy algebra, that

$$\rho\sigma=\phi^2 - \delta^2 \le \frac{1 - \tau^2 - 4\delta^2}{2(1-\tau)}$$

(provided only that $\tau \ne \pm 1$). Clearly the upper limit for $\rho\sigma$ on the right hand side can be made as large as possible only by setting $\delta=0,$ which means $\rho\sigma$ is maximized when $\delta=0;$ that is, $\rho=\sigma.$ In this case the problem of maximizing $\rho\sigma$ is very simple (because $(*)$ becomes linear in $\phi^2$), with solution

$$\rho\sigma \le \frac{1+\tau}{2}.$$

To minimize $\rho\sigma$ we deduce, in the same manner, that we wish to make $\delta$ as large as possible. This leads to $\phi=0,$ whence $\rho\sigma=-\delta^2.$ Again the problem becomes simple, with solution

$$\rho\sigma \ge \frac{\tau-1}{2}.$$

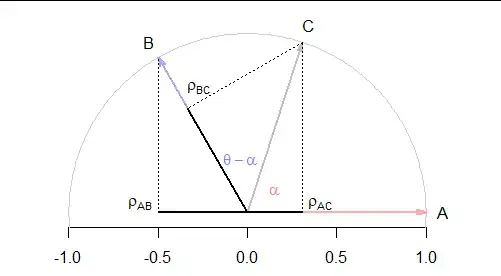

One way to visualize (and check via brute force) these results is to pick $\tau=\rho_{AB},$ plot the region in the $(\rho,\sigma) = (\rho_{AC}, \rho_{BC})$ plane where $(*)$ holds, and overplot contour lines of the function $f(\rho,\sigma)=\rho\sigma.$ The best bounds for $\rho\sigma$ are the lowest and highest contour levels that intersect the region plot.

Here are three examples for typical values of $\tau=\rho_{AB},$ including the case posited by the question, $\rho_{AB}=0.5,$ at the right. The solid regions denote the loci of solutions of $(*):$ that is, the mathematically possible values of the two other correlation coefficients.

The contour lines at levels $(\rho_{AB}-1)/2$ and $(\rho_{AB}+1)/2$ are highlighted: you can see how they just barely skim the vertices of the ellipses determined by $(*),$ osculating precisely at the points $\rho_{AC}=\pm\rho_{BC}$ as deduced in this solution.

It should now be clear that although $\tau=\pm 1$ might have caused algebraic difficulties in the derivation, they aren't really special: the same formulas for the bounds will apply.