Before categorizing outliers, we should first ask whether we are in the right regime for declaring outliers. If we are working with a non-normal distribution — for example, one with exponential behavior — it may be difficult to determine outliers by eye.

In such situations, we may wish to transform such distributions into their normal counterparts before answering that question.

In the process of doing so, you might find that these 'outliers' are no longer really outliers. Consider the following example (in Python):

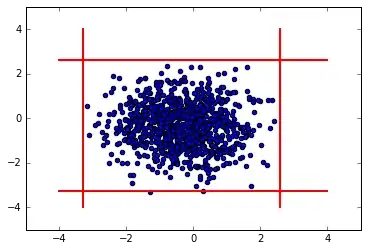

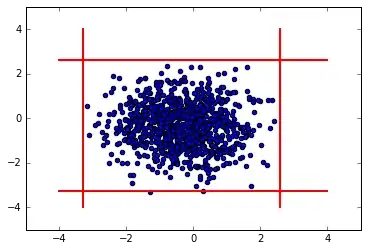

We put together two exponential distributions and make a scatter plot. We draw red lines indicating the 3 sigma deviations from the mean. The area contained within the 3 sigma lines is our 'inlier' region.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

my_array_1 = np.array( np.random.exponential(1, 1000) )

my_array_2 = np.array( np.random.exponential(1, 1000) )

nsig = 3.0

mean_1, std_1 = np.mean(my_array_1), np.std(my_array_1)

mean_2, std_2 = np.mean(my_array_2), np.std(my_array_2)

plt.scatter(my_array_1, my_array_2)

plt.plot([mean_1+nsig*std_1,mean_1+nsig*std_1],[0,8],

color='red', linestyle='-', linewidth=2)

plt.plot([0,8], [mean_2+nsig*std_2,mean_2+nsig*std_2],

color='red', linestyle='-', linewidth=2)

Now we evaluate the fraction of inliers:

frac_inlier = np.mean((my_array_1 < (mean_1 + nsig*std_1))

& (my_array_1 > (mean_1 - nsig*std_1))

& (my_array_2 < (mean_2 + nsig*std_2))

& (my_array_2 > (mean_2 - nsig*std_2)) )

print('Fraction of inliers for untransformed data: %s' % frac_inlier)

And find:

Fraction of inliers for untransformed data: 0.96

A Box-Cox transformation is a general kind of transformation to deal with exponential-like distributions. Let's make such a transformation on our distributions, and perform the same analysis as above.

from scipy import stats

bc_array_1, bc_lambda_1 = stats.boxcox(my_array_1)

bc_array_2, bc_lambda_2 = stats.boxcox(my_array_2)

mean_1, std_1 = np.mean(bc_array_1), np.std(bc_array_1)

mean_2, std_2 = np.mean(bc_array_2), np.std(bc_array_2)

plt.scatter(bc_array_1, bc_array_2)

plt.plot([mean_1+nsig*std_1,mean_1+nsig*std_1],[-4,4],

color='red', linestyle='-', linewidth=2)

plt.plot([mean_1-nsig*std_1,mean_1-nsig*std_1],[-4,4],

color='red', linestyle='-', linewidth=2)

plt.plot([-4,4], [mean_2+nsig*std_2,mean_2+nsig*std_2],

color='red', linestyle='-', linewidth=2)

plt.plot([-4,4], [mean_2-nsig*std_2,mean_2-nsig*std_2],

color='red', linestyle='-', linewidth=2)

frac_inlier = np.mean((bc_array_1 < (mean_1 + nsig*std_1))

& (bc_array_1 > (mean_1 - nsig*std_1))

& (bc_array_2 < (mean_2 + nsig*std_2))

& (bc_array_2 > (mean_2 - nsig*std_2)) )

print('Fraction of inliers for transformed data: %s' % frac_inlier)

This yields:

Fraction of inliers for transformed data: 0.999

So, we see that we have many fewer outliers just by transforming. If you feel that you still must get rid of outliers, you can simply look for points that are outside of the range

$$

mean - nsig*std < x < mean + nsig*std

$$

for each distribution, where $nsig$ is the number of standard deviations beyond which you consider a point to be an outlier (usually 2 or 3).

Finally, should you choose to go this path, I have defined two functions for transforming to and from the Box-Cox transformation as used above:

# Define functions to easily switch back and forth

# between the two representations of loss

def transform_toboxcox(x, lam=lam_bc):

return (x**lam - 1)/lam

def transform_fromboxcox(x, lam=lam_bc):

return (lam*x + 1)**(1/lam)

where $x$ is your data, and $lam$ the lambda returned by your call to stats.boxcox .