In the psychology of perception (psychophysics), for two stimuli to be just-discernible (just-noticeable difference, JND), the difference between their magnitudes (e.g. the pitch or the loudness of two tones) needs to be greater if their individual absolute values are high, a relationship known as the Weber-Fechner law.

Similarly, in numerical cognition (the psychology of numbers), it becomes increasingly difficult to discriminate among two numbers separated by a constant amount, as their absolute values increase (by the same amount).

In other words, the JND depends not (only) on the difference between the stimuli but (also) on their ratio.

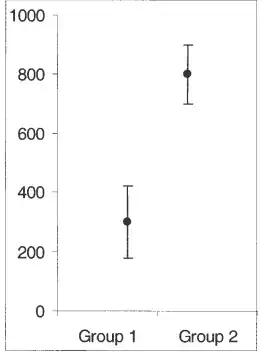

It is tempting to consider whether Weber's law also applies to the statistical significance of the difference between two means, as depicted for instance in the plot below:

But is it not in fact the case that, when the relevant statistics are computed, e.g. independent samples t-test and its associated p-value, it turns out that it is only the difference between the means (plus, of course, the variance that goes into each one of them, and the respective sample sizes) and not their ratio that predicts the p-value that in turn tells us about the significance of the difference between them?