Reading this post by @gung brought me to try to reproduce his superb illustrations, and led ultimately to question something I had read or heard, but that I'd like to understand more intuitively: Why is an OLS lm controlling for a correlated variable better (can I say 'better' tentatively?) than a mixed-effects model with different intersects and slopes?

Here's the toy example, again trying to parallel the post quoted above:

First the data:

set.seed(0)

x1 <- c(rnorm(10,3,1),rnorm(10,5,1),rnorm(10,7,1))

x2 <- rep(c(1:3),each=10)

y1 <- 2 -0.8 * x1[1:10] + 8 * x2[1:10] +rnorm(10)

y2 <- 6 -0.8 * x1[11:20] + 8 * x2[11:20] +rnorm(10)

y3 <- 8 -0.8 * x1[21:30] + 8 * x2[21:30] +rnorm(10)

y <- c(y1, y2, y3)

And the different models:

library(lme4)

fit1 <- lm(y ~ x1)

fit2 <- lm(y ~ x1 + x2)

fit3 <- lmer(y ~ x1 + (1|x2))

fit4 <- lmer(y ~ x1|x2, REML=F)

Comparing Akaike information criterion (AIC) between models:

AIC(fit1, fit2, fit3, fit4)

df AIC

df AIC

fit1 3 184.5330

fit2 4 97.6568

fit3 4 112.0120

fit4 5 114.8401

So it seems that the best model is lm(y ~ x1 + x2), which I guess make sense given the strong correlation between x1 and x2 cor(x1,x2) [1] 0.8619565.

But the question is, What is the intuition behind this behavior, when the mixed model with varying intercepts and slopes seems to result in coefficients that fit the data beautifully?

coef(lmer(y ~ x1|x2))

$x2

x1 (Intercept)

1 -1.1595730 11.37746

2 -0.2586303 19.38601

3 0.2829754 24.20038

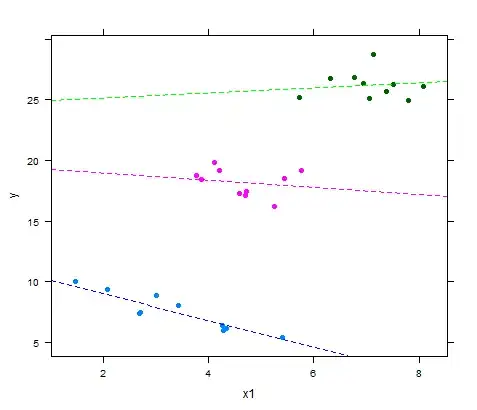

library(lattice)

xyplot(y ~ x1, groups = x2, pch=19,

panel = function(x, y,...) {

panel.xyplot(x, y,...);

panel.abline(a=coef(fit4)$x2[1,2], b=coef(fit4)$x2[1,1],lty=2,col='blue');

panel.abline(a=coef(fit4)$x2[2,2], b=coef(fit4)$x2[2,1],lty=2,col='magenta');

panel.abline(a=coef(fit4)$x2[3,2], b=coef(fit4)$x2[3,1],lty=2,col='green')

})

I do realize that the graphical fit of the bivariate OLS can look pretty good as well:

library(scatterplot3d)

plot1 <- scatterplot3d(x1,x2,y, type='h', pch=16,

highlight.3d=T)

plot1$plane3d(fit2)

... and I don't know if this invalidates the question.

lmer()fits should be fit using ML rather than REML, via this post. Also note the caveats to using the AIC in a mixed model context listed at http://glmm.wikidot.com/faq. – alexforrence Jul 11 '15 at 00:01x2as random makes theoretical and practical sense. – alexforrence Jul 11 '15 at 14:05The grouping factor

x2only has three levels, which limits the practicality of using it as a random effect (also mentioned in the faq). Also, fitting the random slope modelfit4without including the fixedx1term doesn't really make sense.The

– alexforrence Jul 11 '15 at 14:06sleepstudydataset might be more appropriate, and you can tease the same thing out by comparingReaction ~ Days + SubjectagainstReaction ~ Days + (1|Subject).y3to 40. Or swap intercepts fory1andy2. Additionally, I think the intercepts are playing such a large role because of the small sample size (e.g. try increasing to 20 and then 100 per level, instead of 10). Another thing to think about is whether or not you should be treatingx2as a factor:lm(y ~ x1 + as.factor(x2))– Jota Jul 12 '15 at 22:56