Unit testing has something of a mystique about it these days. People treat it as if 100% test coverage is a holy grail, and as if unit testing is the One True Way of developing software.

They're missing the point.

Unit testing is not the answer. Testing is.

Now, whenever this discussion comes up, someone (often even me) will trot out Dijkstra's quote: "Program testing can demonstrate the presence of bugs, but never demonstrate their absence." Dijkstra is right: testing is not sufficient to prove that software works as intended. But it is necessary: at some level, it must be possible to demonstrate that software is doing what you want it to.

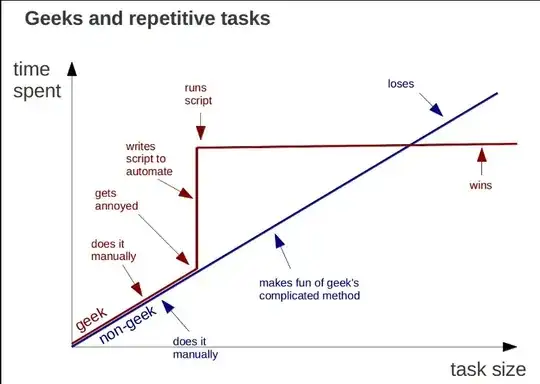

Many people test by hand. Even staunch TDD enthusiasts will do manual testing, although they sometimes won't admit it. It can't be helped: just before you go into the conference room to demo your software to your client/boss/investors/etc., you'll run through it by hand to make sure it will work. There's nothing wrong with that, and in fact it would be crazy to just expect everything to go smoothly without running through it manually -- that is, testing it -- even if you have 100% unit test coverage and the utmost confidence in your tests.

But manual testing, even though it is necessary for building software, is rarely sufficient. Why? Because manual testing is tedious, and time-consuming, and performed by humans. And humans are notoriously bad at performing tedious and time-consuming tasks: they avoid doing them whenever possible, and they often don't do them well when they're forced to.

Machines, on the other hand, are excellent at performing tedious and time-consuming tasks. That's what computers were invented for, after all.

So testing is crucial, and automated testing is the only sensible way to ensure that your tests are employed consistently. And it is important to test, and re-test, as the software is developed. Another answer here notes the importance of regression testing. Due to the complexity of software systems, frequently seemingly-innocuous changes to one part of the system cause unintended changes (i.e. bugs) in other parts of the system. You cannot discover these unintended changes without some form of testing. And if you want to have reliable data about your tests, you must perform your testing in a systematic way, which means you must have some kind of automated testing system.

What does all this have to do with unit testing? Well, due to their nature, unit tests are run by the machine, not by a human. Therefore, many people are under the false impression that automated testing equals unit testing. But that's not true: unit tests are just extra small automated tests.

Now, what is the value in extra small automated tests? The advantage is that they test components of a software system in isolation, which enables more precise targeting of testing, and aids in debugging. But unit testing does not intrinsically mean higher quality tests. It often leads to higher quality tests, due to it covering software at a finer level of detail. But it is possible to completely test the behavior of only a complete system, and not its composite parts, and still test it thoroughly.

But even with 100% unit test coverage, a system still may not be thoroughly tested. Because individual components may work perfectly in isolation, yet still fail when used together. So unit testing, while highly useful, is not sufficient to ensure that software works as expected. Indeed, many developers supplement unit tests with automated integration tests, automated functional tests, and manual testing.

If you're not seeing value in unit tests, perhaps the best way to start is by using a different kind of automated test. In a web environment, using a browser automation testing tool like Selenium will often provide a big win for a relatively small investment. Once you've dipped your toes in the water, you'll more easily be able to see how helpful automated tests are. And once you have automated tests, unit testing makes a lot more sense, since it provides a faster turnaround than big integration or end-to-end tests, since you can target tests at just the component that you're currently working on.

TL;DR: don't worry about unit testing just yet. Just worry about testing your software first.