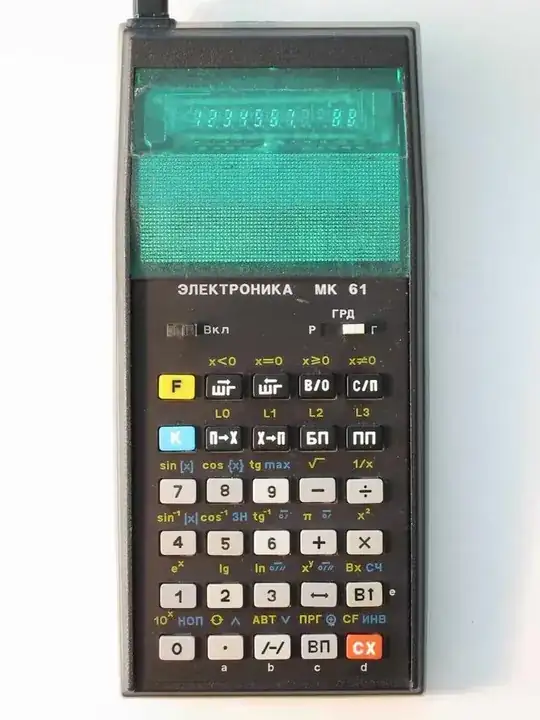

In my childhood I used to program on an MK-61 Soviet calculator. It had four operating registers (X, Y, Z, T) and 15 storage registers. A program could have 105 steps.

As I recall it, it had commands like:

- Swap X and Y registers

- Shift registers (Z to T, Y to Z, X to Y)

- Copy from storage register (1..15) to X

- Copy from X to storage register (1..15)

- If X < 0 then go to program step ##

- Perform operation (+, -, *, /) using X and Y values and put result to X

Is this command set an assembly language? Did I have a basic idea of assembly languages by using this device?

It turns out it is something called "keystroke programming".

Funny fact: a similar calculator (like this one, but with energy independent memory) was used as a back-up hardware for space mission trajectory calculations in 1988. :-)