Perhaps some nouns are used both as animate (Nom=Gen) and inanimate (Nom=Accus), depending on the context.

Like the "добавить в друзья" in social networks. Here the word "friends" is used in the sense of "friend list", not of the humans themselves.

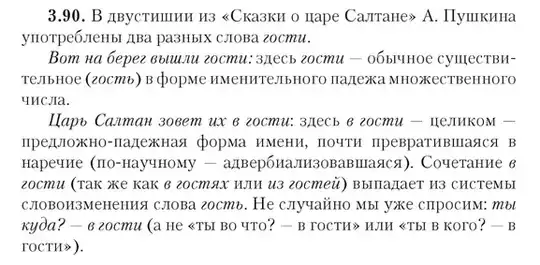

As such, "в гостях" reflects the prepositional usage of в, while "в гости" reflects the accusative usage of a noun which, although derived from the word for "guests", here implies a change in quality/state, rather than the embodiment of the guests themselves.

By the way, remember that лицо is inanimate when meaning "face" and animate as a formal word for "person". Which implies an animate accusative plural in "лиц". Like in the idiom "мера на лиц...", "a measure, concerning [a group of specific] people".

зá мужа, and the semantically weak ending was eliminated by the time it was already an adverb – meaning that animacy wasn't ignored for as long as there was any animacy to ignore. – Nikolay Ershov Sep 12 '16 at 18:27В+animacy-ignoring plural accusative indicating a role of some sort: dozens of examples. (Actually any number of examples, since it's still productive.) Ditto, indicating the name of a territory formed by pluralising the term for its inhabitants: exclusively a limited number of obsolete toponyms (из варяг в греки). I get that it sounds like a cool idea, but your "maybe" is a "probably not". – Nikolay Ershov Sep 15 '16 at 14:13вis ultimately spatial, whether literally or metaphorically. The thing is, what you're suggesting withв гостяхas "in a company of guests" would in fact be a non-metaphorical use ofв. It'sгостяхthat's the abstraction here, a synecdochal reference to a location. Like I said, it's how we tend to intuitively parseв гостяхnowadays, but I maintain that originally, it was much more likely a truly metaphoricalвlike the one inв денщиках— referring to who you are (or "who you're being"), not where you are. Who has more than one valet? – Nikolay Ershov Sep 15 '16 at 22:32