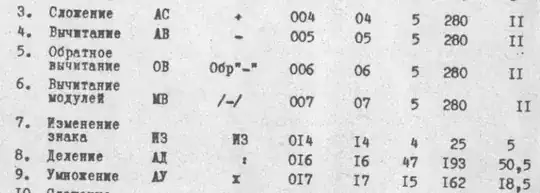

In the BESM-6 technical manuals — for example, in the ALU description, page 4 — there is a table specifying min/max/average instruction latencies in clock cycles (the last 3 columns; the clock rate was 9 MHz):

The rows are:

- Addition, {ACC, Y} := ACC + OP

- Subtraction, {ACC, Y} := ACC - OP

- Reverse subtraction, {ACC, Y} := OP - ACC

- Subtraction of absolute values, {ACC, Y} := abs(ACC) - abs(OP)

- Negation, ACC := OP < 0 ? -ACC : ACC

- Division, ACC := ACC / OP, requires OP to be normalized, otherwise traps.

- Multiplication, {ACC, Y} := ACC * OP

The ACCumulator and the OPerand are in the "simplistic" floating point format: 7 base-2 exponent bits, a sign bit, 40 mantissa bits in 2's complement format. All arithmetic instruction except division and negation produce a result with 80 bits of mantissa: the upper bits in the accumulator, the lower bits in the separate Y register.

The question is, how come the additive operations can take up to 280 clock ticks? Unlike multiplication and division, addition requires equalizing the exponents by shifting the mantissa of one of the operands to the right, 1 bit per cycle; if there was no circuit terminating the equalization early as soon as all significant mantissa bits of the operand with the smaller exponent were shifted away, the process might take up to 127 cycles; but then the actual addition, performed as parallel bitwise 3-to-2 reductions, until no carries are left to reduce, should not have anything left to do. Then, normalization to the left might take up to 128 cycles, for at most 256 plus a handful, when zero with the lowest exponent is added to zero with the highest exponent. Still, quite far from 280.

My experiments implementing the algorithm deduced from the documentation show the following statistics, out of 100 million trials each:

Integer addition (equal exponents in the operands, final normalization to the left is disabled):

min = 5, max = 31, avg = 9.66, median = 9

Obviously, the theoretical maximum would be a shade greater than 40, when adding -1 and 1.

Completely random floating point addition (arbitrary exponents, arbitrary potentially denormalized mantissas):

min = 5, max = 169, avg = 51.30, median = 46

Requiring mantissas of the operands to be normalized:

min = 5, max = 151, avg = 50.28, median = 45

Further clamping operands to be within approx. 6 decimal orders of magnitude (absolute difference of exponents no more than 21) of each other, quasi-normally distributed:

min = 5, max = 63, avg = 13.66, median = 13

Thus, the claim of the average (or, more likely, median) latency being 11 cycles, given an equal mix of integer and floating point additions, is substantiated, but the maximum of 280 cycles is a mystery.

IIin the last column mean? – Omar and Lorraine Jan 09 '19 at 09:430andO. – Alex Hajnal Jan 09 '19 at 13:32+,-operations...*,/do not need it .... also how much bits the ALU use for computation? IIRC FPUs have more bits for accumulator/subresult than the internal representation of number to increase precision of division ... – Spektre Jan 09 '19 at 14:03Ifor 1, so that it could be used for (small) Roman numerals as well.Уwas used instead ofV, andПandШcould be used for "kerning" ofIIandIIIresp. ;DandLwere missing, but numbered lists don't usually go that far;Dis not needed for years since 1900 (MCM), andLcould be approximated withЦand a touch of whiteout. – Leo B. Jan 10 '19 at 19:10