TL;DR: Upper Case Is the Default for Latin Script.

Latin script is based on upper case and designed around that. Lower case is a later add-on (see below) for cursive. Default use-case for Latin script is Upper-Case.

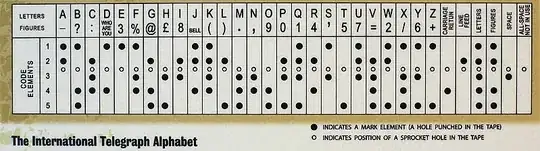

Character Encoding

Early codes and machinery used for writing didn't have any case at all, only letters. Lower and upper case glyphs are eye candy, usually not conveying any substantial meaning. That's why neither Morse nor Braille carry them. Same goes for any other early transmission code, like the the ITA2 used for teletypes.

After all, there is no need to have two sets when they are fully complementary. It wasn't until the mid 1960s that, with the upcoming ASCII encoding, lower case became a choice to be used.

Printing Requires a Choice

The whole point of choosing what case to be used only arises with the need for displaying those letters in print, or later on screen. Here using upper case is only natural, as

Upper Case is

most commonly accepted

across Europe, independent of culture and writing style due to being the oldest form.

most readable,

due to being a two line script (*1) developed for best readability (*2) - a feature that comes in quite handy with low quality output (*3).

most inclusive / least offensive one.

Writing all all upper case will always be proper, while writing all lower may be offending to some - such as when addressing a person.

Then There Was Data

When it comes to data handling, it's important to remember that letters were only added as an afterthought. Punch cards, the earliest means of data storage, only had numbers at first. Next, some punctuation (decimal point, currency sign, hash, etc) were added, and finally letters were the last major modification.

The same goes for equipment to print from punch cards (printing tabulators) or onto punch cards (interpreters). They originally also could do only numbers and punctuation: letters were added later. Powers first in 1921, while IBM followed in 1931. Of course, when printed they were done so in upper case.

It wasn't until the mid 1960s that lower case became a distinct, additional set on punch cards and mainframes.

But I Type Lower Case

Not really. Early machinery, no matter whether teletype or terminal, did not produce lower or upper case when typed, but just letters, as there was no case (see above). This single case was usually displayed as uppercase (reasoning see above).

The Apple II is eventually the last major application of that principle. pressing a letter always produced only a single code, no matter whether Shift was pressed or not, and this letter was displayed in upper case.

Almost all early computing equipment worked similarly. When terminals allowing entry of lower and upper case letters became a thing, mainframes still only got a single case delivered as communication equipment (terminal controllers, I/O handler) simply converted both to the single encoding the host used.

That way, terminals with lower case and those without would by default be operated all equally, allowing a smooth transition and high degree of compatibility.

Then Why is Unix Lower Case?

The main purpose of low end machines of the 1970s was about to get any work done. Translation layers, such as the ones common in mainframes, were a luxury one could do without. Unix was a prime example as it was all about getting a certain functionality to production. Combine this with now widely available (ASCII-based) lowercase enabled terminals and one gets lower case as default input. Including all the hassles of case sensitive input.

CP/M and in turn MS-DOS are nice counter examples as here the command line is by default translated to upper case, simplifying handling.

Bottom Line

There is no single reason and especially not one constructed in afterthought. It was an evolutionary process influenced by need, capabilities and usage.

History is Upper Case

Latin, developed around 7th century BC was originally a two line script(*1).

By the first century AD papyri show sloppy written letters forming lower case (minuscule), which developed into Roman Cursive.

By the 8th century those forms had developed into Carolingian Minuscule similar to today's lower case (*4).

It took another 300-500 years (11th/13th century) for Gothic script (Blackletter) to finalize them into what we know today.

Rules of when to use upper and lower case only became widely accepted during the 16th/17th century, not least by development of the printing press.

The English way of writing mostly lower case is even more recent and dates to the early 18th century.

Bottom Line: Throughout history it was Upper-Case first.

*1 - Two line scripts, like old Greek and Latin, use a single case with all letters of the same height, limited between those two lines. Lower case needs three lines, or four with descender (itself a later, Gothic addition). Might remind you about school, perhaps? :))

*2 - Roman Majuscule developed to be readable from distance and on low quality material. Roman Minuscule is a form of shorthand, trading readability for space usage and speed in writing(*5). More appropriate for notes and private correspondence than official exchange.

*3 - Note that your keyboard is (most likely) also labelled with upper case letters. That's a convention since early typewriter days. They are until today more easy to identify than lower case - so not (only) heritage.

*4 - Greek Minuscule was developed in Byzantine Empire about 100-200 years later, which also explains why Cyrillic has distinct lower case forms for only some of the letters as it got defined before the process of developing lower case for Greek was concluded.

*5 - Ligatures make a great point here. They were a further evolution promoting increasing density and speed of cursive - and almost exclusively found with lower case letters. While usually not considered letters on their own, typesetters had dedicated letters for each ligature.