TL;DR: CPUs handle Zero unique among all integers.

Zero is set apart from any other integer by the way ALUs work. On low level it is thus of advantage to use zero as return code for success, as it's the most easy to be detected. With that being said, it comes natural to extend this to process/program return codes.

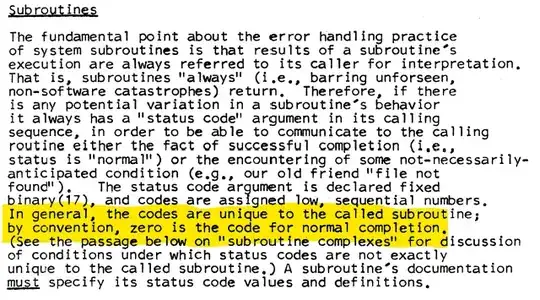

Way Back in Time and Close to Hardware

Much meaning can be put in hindsight onto return codes, but such based on integers inherently benefit from integers being treated as first class member by next to all CPU architectures. This includes almost always a way for taking execution depending on an integer being zero or non zero. Either by offering a value based branch, or a fast, low cost test followed by a branch.

At that point its helpful to keep in mind, that error handling is a burden slowing down execution. A substantial one, considering that programs are all about calling functions - within and from the OS.

By assigning zero as default value for success this advantage can be used for cheap (*1) error/non-error detection, reducing error handling cost to a possible minimum.

Of course that argument might work either way, but when looking at ordinary execution, then functions will usually will have have to be way more differentiated why they failed than why they succeeded. Reserving one return code for success and MAX_INT-1 for error numbers does again simplify error handling. Of course a differentiated error handling with multiple fields and structure past a simple number will beat all of that - but also be an overkill in 99.999% of all cases.

And then there was C and Unix

While (early) mainframe OS used dedicated mechanics for success and return/error information, the designers of Unix were all about simplifying to the absolute minimum. Using zero to distinguish the most notable case, yields the best performance.

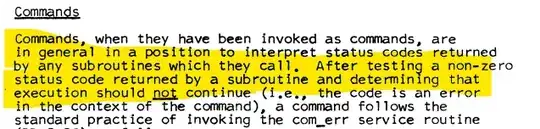

C/Unix was not only using the advantage of integers within programs (*2), but as well extended it to the shell. After all, a programs main() is also just a function, so why bother to convert this in any way but simply forwarding that value to shell?

The C Programming Language Second Edition mentioned this as general rule on p.27:

Typically, a return value of zero implies normal termination;

non-zero values signal unusual or erroneous termination conditions.

Divide et Impera

What goes for integers works of course as well with signed integers. Those divide all none zero values in two (almost) equal sized sets, marked by the sign - a feature as easy to detect as like zero and as well privileged by many architectures.

By using signed integers Now not only reasons for being non successful, but as well reasons for success can be reportet. C does make as well use thereof (*3).

Two Halves of a Shell

(*4)

Despite process exit codes usually seen as unsigned integers, the sign principle got as well extended to shell use by reserving values of of 128 and above, like for the return value of a sub-process.

One Exit Code to Rule Them All

In batch programming 'success' is one most important 'message', as it's the one to be detected to carry on with whatever is next. Think of a very classic use case like processing data from a tape. Such a program may return beside the basic

- Everything worked fine and

- Generic fail

exit codes for

- Wrong tape,

- No tape assigned or

- Add follow up tape

Depending on the environment the later may require the request of operator assistance to mount the right tape, a follow up tape or search an archive. All things the data process can and should not do on it's own, as it's heavy dependent on customer installation what the right handling will be.

Again the privilege of zero being special for all integer makes batch writing consistent, easy to do and most important, easy to read. Anyone who has worked in a (classic) data center will know how important a consistent structure of batch files is.

Long story short:

Zero is privileged as return value by hardware, assigning it to the most common case comes naturally

*1 - In a sense of compact code and fast execution.

*2 - Immortalised by the ubiquitous `if (rc) { /*errorhandling */ };

*3 - Of course it wouldn't be C if it doesn't get complicated at that point, for example with read() now only reserving -1 for some error and reporting the real error number in errno, adding several pitfalls in non trivial programs :)

*4 - In some ways the usage of signed integers and the resulting easy detection of positive and negative values and zero is much like the shell of a Bivalvia: Two valves connected by a hinge :))