Intel had a rather complex bunch of hardware to compute a floating-point quotient in a way that yielded two bits per iteration, which required having a rather large table listing all the combinations of bit patterns where part of the quotient should be 11 [rather than listing all patterns individually, the table would have had entries where each bit may be 0, 1, or X, such that e.g. a bit pattern of 100X01X would match 1000010, 1000011, 1001010, or 1001011, so the table didn't need an impossibly huge number of entries]. Unfortunately, part of the table got corrupted when it was being transferred from whatever tool was used to generate it, into the chip design.

I find this approach to division somewhat curious, since it would have been quick to examine the divisor and produce a value which, when multiplied by both the divisor (rounding up) and dividend (rounding down), would force the new divisor to have its upper bits equal to 0.1111 or 0.11111111, which would make it easy to extract 4 or 8 bits per iteration. The final quotient would likely be slightly less than the correct value [never greater, given the directions of rounding earlier], but it would be close enough that only two or three couple of successive-approximation steps should be needed at the end to clean things up.

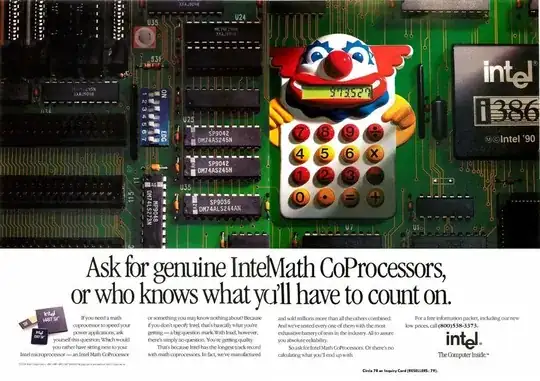

In any case, the ultimate irony with the Intel FDIV bug is that, earlier, during the 386/387 era, there was a competing product by Weitek which could perform single-precision floating-point math much faster than Intel's chips, but didn't do double precision math at all. Some programs which would normally have used double-precision math shipped versions for the Weitek which used single-precision math and thus produced less accurate results. Intel's marketing team decided to exploit this (designed, and regarded as acceptable) lack of precision by producing an ad which showed a motherboard with a dime-store calculator decorated with clown graphics where the CPU should have been, and the caption "Ask for genuine Intel Math CoProcessors, or who knows what math you’ll have to count on".

f''(x) = -f(x)thenf(x) = cos(x)? I'm not a quant, I'm speculating wildly. – Tommy Oct 12 '20 at 20:08mfenceto serializing OoO exec, disable the uop cache for JCC at a 32-byte boundary – Peter Cordes Oct 14 '20 at 03:083.11-3.1=. On Windows 3.10, the calculator will display "0.00", On Windows 3.11, the calculator will display "0.01". This issue is somewhat similar to a bug that was in in theprintffor Turbo C 2.0 but fixed in 2.1, whereprintf("%1.1f", 999.96);would output 000.0 [it would determine that the value was at least 100 but less than 1,000 and thus needed three digits to the left of the decimal... – supercat Oct 15 '20 at 17:25