Why should we use inverse QFT instead of QFT in Shor's algorithm? When I tried to simulate Shor's algorithm for small numbers, I got an answer even when I used just QFT instead of inverse QFT.

-

1How did you simulate the algorithm? Could you give the details? – Sanchayan Dutta Jun 09 '19 at 08:13

1 Answers

For Shor's algorithm, it actually doesn't matter which one you use.

If you apply the QFT twice, it is equivalent to a classical multiplication by -1 modulo $2^n$ where $n$ is the size of the register. That is to say, it reverses the order of all of the computational basis states except for $|0\rangle$ which stays where it started. $|k\rangle$ becomes $|-k\rangle = |2^n - k\rangle$.

Now, in Shor's algorithm, the output of the QFT is a state with amplitudes whose magnitudes are approximately periodic with a period that divides $2^n$. This isn't a coincidence; it's crucial to how the whole algorithm works. Because the period is a divisor of the number of computational basis states, reversing their order has a negligible effect on the state. Therefore there is little difference between using the QFT and the inverse QFT, because $\text{QFT}^{-1} = \text{QFT} \cdot \text{QFT}^{-1} \cdot \text{QFT}^{-1} = \text{QFT} \cdot \text{Mul}(-1)$.

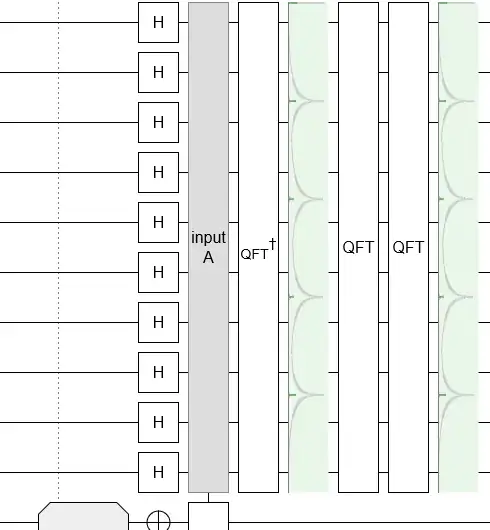

Note how the probability distributions are almost identical after an inverse QFT or after a QFT (in the above diagram the second qft is just to undo the inverse QFT). Since the output distribution is nearly identical the algorithm works either way.

- 36,389

- 1

- 29

- 95

-

Do you have a mathematical demonstration of this |⟩ becomes |−⟩=|2^−⟩? If you apply the QFT twice, it is equivalent to a classical multiplication by -1 modulo 2 where is the size of the register. That is to say, it reverses the order of all of the computational basis states except for |0⟩, which stays where it started. |⟩ becomes |−⟩=|2^−⟩. – Parfait Atchadé Aug 23 '23 at 09:44

-

@ParfaitAtchadé https://algassert.com/quirk#circuit=%7B%22cols%22%3A%5B%5B%22H%22%2C%22H%22%2C%22H%22%2C%22H%22%2C%22H%22%2C%22H%22%5D%2C%5B%22%E2%80%A2%22%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22X%22%5D%2C%5B1%2C%22%E2%80%A2%22%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22X%22%5D%2C%5B1%2C1%2C%22%E2%80%A2%22%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22X%22%5D%2C%5B1%2C1%2C1%2C%22%E2%80%A2%22%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22X%22%5D%2C%5B1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22%E2%80%A2%22%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22X%22%5D%2C%5B1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22%E2%80%A2%22%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C1%2C%22X%22%5D%2C%5B%22QFT6%22%5D%2C%5B%22QFT6%22%5D%5D%7D – Craig Gidney Aug 23 '23 at 20:52

-

many thanks for the quirk. I understand the scheme. I would like to understand the demonstration of QFT(QFT)|x> = |-x>. Do you have the demonstration? Many thanks. – Parfait Atchadé Aug 24 '23 at 21:09