The standard methodology for a single "variable" (such

as price-to-book) is this: 1. Sort the stocks in the

cross-section at a specific point in time by that

variable. 2. Compare the subsequent returns of stocks

that have a high value of the variable, with returns of

stocks that a low value of the variable. To do this

comparison, you'd take the difference between the

returns of high-value-of-variable stocks, and returns

of low-value-of-variable stocks. This, in turn,

corresponds naturally to being long one portfolio of

stocks (high-value-of-variable), and being short another portfolio

(low-value-of-variable).

Statistically, if there is a monotone relation between

the variable and subsequent stock returns, the spread

in returns will be greater if you look at long/short

portfolios, and so the power of your tests increases.

(That is, the relation between variable and return is

easier to spot.)

That being said, as an investor, you will want to

analyze to what extent long and short positions have

contributed to total return. For instance, if you find

that the short portfolio was responsible for a substantial

portion of total return, then not implementing it

would mean the strategy becomes less attractive. (But

of course, it need not be an actual short position. As

pointed out in the comment by nbbo2, it might be a

negative active weight relative to a benchmark.)

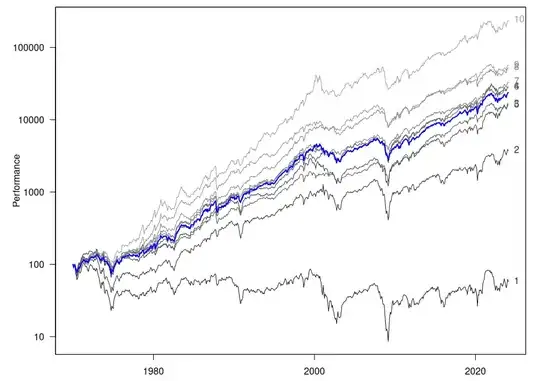

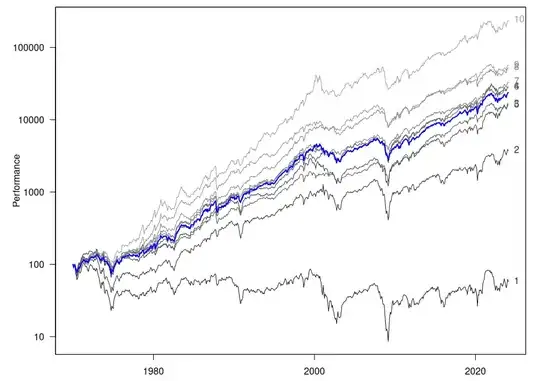

Kenneth French publishes several datasets that show the

returns of the original sort portfolios, i.e. not just the

long--short aggregate returns. For instance, momentum

(i.e., the variable you sort on is 1-year return). The

figure below shows the total returns of 10 momentum

portfolios since 1970, with 10 being the high-momentum

portfolio and 1 the low-momentum portfolio (the lighter

the grey, the higher the momentum). In blue, I have

added the market return.

library("NMOF")

library("zoo")

library("PMwR")

P <- French(dest.dir = tempdir(),

dataset = "10_Portfolios_Prior_12_2_CSV.zip",

weighting = "value",

price.series = TRUE, na.rm = TRUE)

P <- window(zoo(P, as.Date(row.names(P))),

start = as.Date("1969-12-31"))

M <- French(tempdir(), dataset = "market",

price.series = TRUE, na.rm = TRUE)

M <- window(zoo(M, as.Date(row.names(M))),

start = as.Date("1969-12-31"))

greys <- grey(seq(.1, .6, length.out = ncol(P)))

par(las = 1, mar = c(3,5,1,2))

plot(P <- scale1(P, level = 100),

plot.type = "single", log = "y",

xlab = "", ylab = "Performance",

col = greys)

lines(scale1(M, level = 100), col = "blue", lwd = 2)

par(xpd=TRUE)

text(x = max(index(M)), y = c(coredata(tail(P, 1))),

labels = 1:10, pos = 4, col = greys)

par(xpd=FALSE)

As you can see, the

high-momentum portfolio beats the market, while the

low-momentum portfolio underperforms. The headline

"momentum-return" number aggregates both sources of

outperformance.