Is it possible to fill the $121$ entries in an $11\times11$ square with the values $0,+1,-1$, so that the row sums and column sums are $22$ distinct numbers?

-

2Seems like a relatively simple dynamic programming or backtracking problem – qwr Jan 06 '16 at 15:01

-

4I suspect that it is impossible for all odd sized squares, given that it's easy to brute force squares 3x3 and 5x5, and those have no solutions. – qwr Jan 08 '16 at 05:19

-

3@Gamow Do you know the solution? – xnor Jan 11 '16 at 22:30

-

@Gamow please feel free to answer question for bounty. – martin Jan 13 '16 at 13:49

-

I imagine the answer is no if no-one has got it yet – Beastly Gerbil Jan 15 '16 at 19:23

-

4I ask this question of mathoverflow, it is impossible, see http://mathoverflow.net/questions/228525/reverse-definition-for-magic-square – Jan 16 '16 at 13:24

-

@MeysamGhahramani The joy in doing these problems is found in personally (or with others in real-time) deriving an elegant, general proof, possibly going through an ugly, specific case. Admittedly, we are (or at least I am) currently at an ugly detour stage. Nevertheless, thank you for noting the solution - it gives some incentive to continue the journey. – Lawrence Jan 18 '16 at 16:21

-

is there a solution or people are wasting their time to proof it is not possible? – Oray Jan 20 '16 at 05:59

9 Answers

I've found a solution here, which I've decided to blatantly steal since I think a lot of people really want to see a fully worked out solution. It is indeed impossible. The same method below can be used to show that a valid $n\times n$ matrix can only exist if $n$ is even and the missing sum is $\pm n$.

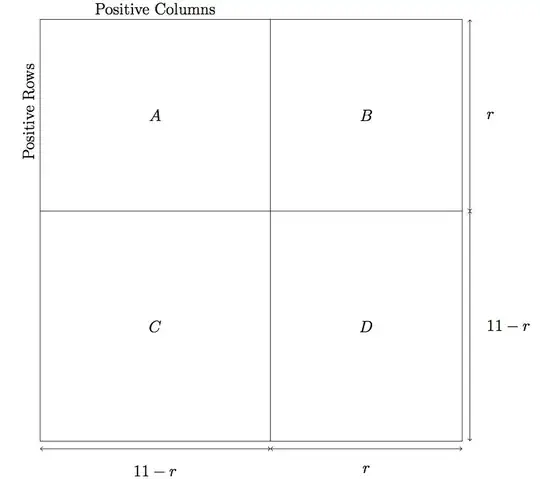

Let's say the missing sum is $m$. We can assume by symmetry that $m\le 0$. There are 11 rows and columns whose sum is positive. Let's rearrange these positive row/columns so that they are all on the top/left of the matrix. Assuming there are $r$ positive rows, this means there are $11-r$ positive columns. Let's group all the positive columns on the left, and all positive rows on top. See the picture at the bottom, where I've given labels A, B, C and D to four quadrants of the matrix.

Now, let $a$ be the sum of the numbers in section A, and the same with $b,c,d$. Then $$\begin{align} a+b+c+d &=(\text{sum of all rows and columns})/2\\ &=((-11)+(-10)+\dots+11-m)/2\\ &=-m/2 \end{align}$$ We also know that $$ \begin{align} (a+b)+(a+c) &=\text{sum of all positive rows/columns}\\ &=1+2+\dots+11\\ &=66 \end{align}$$ Combining these last two observations, $$ -m/2=a+b+c+d=(2a+b+c)-a+d=66-a+d $$ Here's the kicker. There are $r(11-r)$ entries in section $A$, meaning that $a\le r(11-r)$. No matter what $r$ is, the quantity $r(11-r)$ is at most $30^*$. Similarly, $d\ge -30$. This means that $$ -m/2\ge 66-30-30=6, $$ implying that $m\le -12$, a contradiction.

${}^*$ To make this proof to work for a general $n\times n$ matrix, instead of just $n=11$, use the inequality $ab\le (a+b)^2/4$, which shows $r(n-r)\le n^2/4$. We then get that $-m/2=\frac{n(n+1)}2-a+d\ge \frac{n(n+1)}2-\frac{n^2}4-\frac{n^2}4=n/2$, implying that $m\le -n$, which means $m=-n$. Since the missing sum must be even, this means $n$ must be even.

- 32,336

- 6

- 92

- 237

Partial answer (fixing earlier mistake)

The possible outcomes of a sum of 11 values (0, +1 or -1) can be any integer number from - 11 to + 11, leaving 23 options total.

Theory on combining resulting numbers:

It's fairly trivial to state that if '11' occurs (a row/column with all 1's), there can never be a column/row totalling '-11' or '-10', due to one of the rows/columns holding a '1' (you can at lowest reach -9 then). The other way around, you cannot have '-11' and expect to be able to squeeze in 10 or 11.

What we learn from this:

11 and -11 cannot occur in scenario's with one of them in a column, and the other in a row

Note: the above is where I went wrong: I first assumed they couldn't appear together at all, which is false - as pointed out in the comments

For ease of further explanation, assume both 11 and -11 to be in rows (all that follows would be similar but mirrored along the diagonal).

If 11 and -11 both take up an entire row, this means in columns you can at extremes reach -9 and +9. If we want 10 and -10 to be able to appear, those have to be in rows aswell (with 10x '1' or '-1' and one zero). This means we already have 4 rows occupied.

It now gets harder though:

if we aligned the 'zeroes' from the '10' and '-10' rows below eachother, we can get at most +7 and -7 in a column, if we didn't we can get +8 or -8 at most. Either way we can only create +9 and -9 in rows again. We can do this two ways: 9x '+-1' and 2x 0, or 10x '+-1' and 1x '-+1'

What can we squeeze into columns now?

so far, the rows from -11 and 11 cancel eachother out, the rows from -10 and 10 allow for a maximum of +1 or -1 variance on the two rows occupied, and the rows from -9 and 9 for a +2 or -2 variance on the two rows those occupy. So with 5 rows left a column value can now hold at most +-5 (+-3) , which also implies we can now actually squeeze our next step (+8 and -8) into columns.

Option 1: Put the '8's in columns.

This means we've used up all variance on the remaining 9 columns, so we have 9 columns which can at most hold +-5. This also implies both 7's and 6's will have to go in rows. The 11's, 10's, 9's, 7's and 6's hog a combined 10 out of a possible 11 rows.

Is there a way to build the 7's and 6's in the column's that leaves sufficient different value numbers to be built in the colums? This will most likely imply 7's and 6's to be built to a maximum from -1 and +1's rather then 0's, to allow sufficiëntly high values in the collumns). Key might be to try and ensure the presence of the +-4 and +-3 in the colums as a guide to figure out how to place the several +-1's to create 6/7 rows.

Option 2: Put the '8's in rows

It's not because we CAN put the 8's in columns, we have to.

Option 3: Put one of the 8's in a column, the other in a row.

Besides option one and two, there's still a third option, and that's to go both ways.

I may have to put this train of thoughts on hold for now, as there doesn't appear a simple path further down. The thing is: The more you keep pushing things with very similar patterns for the '+' and '-' variation in rows, the bigger the chances you'll have issues fitting in 5's and 4's in columns. If the '+1' and the '-1' from the '+' and '-' version of the larger sums keep cancelling eachother out in the column totals, suddenly it appears 4's and 5's turn seemingly impossible to fit in. (or maybe I just haven't spotted how).

- 4,349

- 21

- 37

-

3That was my first thought also initially but both 11 en -11 can exist easily. fill the first row with +1 and the second row with -1. It's just that when a row has 11 a column can't have -11 – Ivo Jan 06 '16 at 09:17

-

1@dmg - thanks for the spoiler edit - I'm somehow always struggling to put multi-line blocks in spoilers – Tim Couwelier Jan 06 '16 at 09:17

-

@IvoBeckers : Oh dear. This seemed to easy for a question by gamow.. I'll try to build on it though – Tim Couwelier Jan 06 '16 at 09:19

-

-

3@TimCouwelier but I think this is the right track to take. Let's say that if both 11 and -11 exist and they both are rows you also know that the columns can only range from -9 to 9 meaning that -10 and 10 also must be rows, and maybe you can go on like that – Ivo Jan 06 '16 at 09:22

Partial answer

As Tim pointed out

If you have rows with sums of -11, 11 and 10, that quickly limits the different numbers you can generate in the columns. Experimentally you can fit in ±11, ±10, ±9, ±8, ±7, ±6 and ±5 but there isn't anywhere to put ±4. If I miss out -10 then I can get to ±3 but there isn't anywhere to put ±2.

And the big problem is that

you need at least ±11 and one of ±10 just to be able to complete the square.

This is because

the row and columns use 22 of the 23 sums but they must sum to the same number so the missing sum must be even.

By contrast, even squares are quite easy; there's a simple pattern whereby you fill a 2n square with n 0s, 2n² 1s and 2n²-n -1s. (Hint: 2n²-n = 2n(2n-1)/2.) Example for 6x6:

1 1 1 1 1 1 6

1 1 1 1 1 -1 4

1 1 1 1 -1 -1 2

1 1 0 -1 -1 -1 -1

1 0 -1 -1 -1 -1 -3

0 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -5

5 3 1 0 -2 -4

My best effort so far for 11x11:

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 11

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 10

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 -1 8

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 -1 -1 6

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 -1 -1 -1 4

1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 -1 -1 -1 1

1 1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -3

1 1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -5

1 1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -7

1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -9

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -11

9 7 5 3 0 0 0 -1 -4 -6 -8

As you can see ±2 are missing, but I'm sure that the fact that you can't get those diagonals to meet must be a factor somehow.

- 423

- 4

- 7

-

Could we, based on the column/row sums matching, figure out that if only 22 out of 23 possible combinations are formed, which of the 23 are options for the one NOT being used? (I.E. '0', 'any odd number', 'any even number, ..') This could make it easier to figure out if any number strictly HAS to be in there. – Tim Couwelier Jan 06 '16 at 13:11

-

1

-

1If you make one of the zeros in the 5th, 6th, or 7th columns a 1, you'll get a 2 on the right side and a 1 on the bottom, getting you a step closer. – Ian MacDonald Jan 06 '16 at 19:24

Taking the example:

for $n=6$, where the greyed cells are the totals of their respective columns and rows, and the top-left cell is the total of each greyed column/row, I am fairly certain that it is not possible for the following reasons:

1) The top-left cell must $=\pm n/2$

2) The only excluded integer in the range $[-n,n]$ must be either $-n$ or $n$.

As noted by @kaine below, these statements are identical, so a proof of either would be enough to show that solutions are not possible for odd $n$. Both are purely observational though, and the bounty will go to a proof (or disproof?!) of the above.

NB

This Mathematica code doesn't check all possiblilities (rather large for $n=11$), but checks the most likely (and returns nothing for test@11).

- 1,979

- 1

- 11

- 17

-

1

-

@kaine that's because I've set the tollerance to only include 1 zero per row/column (reduces computation for larger $n$). Can provide complete code for $n$ if desired, but computational time increases exponentially (hence cutbacks). Please let me know if you require complete solution code. – martin Jan 11 '16 at 20:59

-

@kaine alternatively, increase tollerance by adding

&& \[Or] Count[#, 0] == 2, etc. totest[n_]function. I addition to including all zeros, for complete check, changeSubsetstoTuples. You will see then why I cut back! – martin Jan 11 '16 at 21:02 -

1Um, I'm not sure what you mean by that. I just mean that since the sum of all rows ($R$) equals the sum of all columns ($R=C$) which equals the sum half the sum of all numbers ($\sum_{x=-n}^nx=0$) minus the missing number $y$. This means $\sum_{x=-n}^nx-y=R+C$ goes to $R=C=-y/2$. If you assume 2, 1 is true. If you assume 1, 2 is true. Those two statements are indistinguishable. – kaine Jan 11 '16 at 21:06

This is not possible.

Of course, the more interesting question is the generalized solution to:

Given a square with $N$ columns and $N$ rows, is it possible to have $2N$ unique sums of columns and rows?

First, we need to consider two properties of an $N\times N$ matrix:

For a given matrix with $N$ columns and rows, the range of possible value are $2N + 1$ (in the range $[N, -N]$) and $2N$ sums of values ($N$ columns and $N$ rows). This means there is $1$ and only $1$ "missing value" $M_v$ in the series.

There are also $N^2$ places to fill. This means we need to be at least efficient enough to have $2N$ values using $N^2$ places.

Next, consider a matrix where $N$ is even and it has $2N$ unique sums:

First, assume $N = M_v$. By placing values in the left column and upper row starting with $-N$ descending, we can place unique, sequential values until there are 2 columns and 2 rows remaining. At this point, the sums of all the columns and rows adjacent to the $2 \times 2$ matrix is $0$. It is then trivial to demonstrate that this matrix can produce the remaining values required. This same technique also works when $-N = M_v$.

Since we have $2N$ values to produce, and with each iteration we produce 2 unique values, we cannot be less efficient or else we cannot produce all of the required values. However, when $N$ is odd we should note another property of the matrix:

Each value $(1, 0, -1)$ added to the matrix will result in an even change to the sum total of the matrix columns and rows. Therefore the sum of the columns and rows must be even.

Also note that sum of the columns ($C_v$) and rows ($R_v$) is equal to $-M_v$. ($C_v + R_v = -M_v$ or $C_v + R_v + M_v = 0$). This means that $M_v$ cannot be odd because it is impossible for the sum of the columns and rows to be odd.

So, when $N$ is odd, the missing value $M_v$ cannot be $N$ or $-N$.

That leaves only the possibility of including both $N$ and $-N$ in the matrix, but to do this we must put them both in columns (or rows). Once this is done, observe that there are $N - 2$ columns and $N$ rows (or vice versa) remaining. This allows for $N + (N - 2) = 2N - 2$ unique sums of columns and rows but leaves only $N(N - 2) = N^2 - 2N$ places.

For example, when $N = 11$, after placing $11,-11$ we now have $9 + 11 = 20$ sums but only $9\times 11 = 99$ places. Previously, we demonstrated that for $2N$ values we needed $N^2$ places which, for $N = 10$, is $20$ sums and $100$ places. So when $N$ is odd, after placing $2$ numbers ($N$ and $-N$), we have to be more efficient in order to succeed. Maybe a rectangle can be more efficiently filled (requires fewer available spaces) than a square matrix?

With that assumption, after placing $N$ and $-N$, we can continue to place sequential numbers (like $N-1$ and $-(N-1)$) but that will fill columns (or rows) very quickly (approaching $N + N/2$ instead of $2N$ sums) and reduce the "available spaces" below $N^2 - 2N$ making it easier to consider $M_v$ as $N-1$ or $-(N-1)$.

So if we can skip either $N - 1$ or $-(N - 1)$ then we will explore further. To start we can try the alternating values in columns/rows that we used when $N$ was even. That produced 2 unique values for each column/row pair that was eliminated. It is not possible to be more efficient than that. However, after placing $N$, $-N$ and either $N - 1$ or $-(N - 1)$, we have used 3 columns (or rows) almost entirely identical. The third column contains a $0$ that must be in the second from the top position to allow $N - 3$ in the second row.

If we subtract a row for each column as is required, until there remains only 1 column. Based on the pattern as described above there will be $4$ rows ($4$ remaining spaces; with an even numbered matrix, the 4 remaining spaces were in a square, not a column). However, there are only $3$ possible values (1, 0, -1). This will result in a duplicate value being placed. A duplicate value means a second "missing value" somewhere else in the matrix, since we cannot increase the number of sums produced. This means we cannot have $22$ unique values for an $11\times 11$ matrix (or any odd sized matrix). We can, at most, have $21$ unique values (or $2N - 1$).

Thus, even if it is possible to efficiently fill a square of size $N$ where $N$ is odd, the constraints on how the values are placed reduces the number of unique sums to below $2N$. (Note: I think there is a method to prove that when $N = 11$ there can be at most $19$ unique values, but I'm still working on it...)

- 221

- 1

- 4

-

Well, I haven't actually bothered to read your answer, but I have 2 points to make. 1. Use MathJax. Your equations are fairly simple, you could learn MathJax to type them out. 2. You have used too many spoilers. You could just state at the top in bold letters, that this is a partial proof. The whole objective of spoilers is that people don't read the answer by accident, and I don't think that is going to happen anyways for such a long post. – ghosts_in_the_code Jan 12 '16 at 17:29

-

Thanks for the pointers... I'm looking at MathJax. And I'm not sure how to use spoilers, so I'll try to edit it to improve it after looking at that. – Jim Jan 12 '16 at 17:59

-

Your last statement that for $N=11$ there can be at most $19$ unique values isn't correct. I have created multiple squares with $21$ unique sums. – dpwilson Jan 14 '16 at 19:58

-

2I have a lot of trouble following this answer and can't really understand what's going on in the last paragraphs. It could use some clarity, even after the edit. – Fimpellizzeri Jan 14 '16 at 20:15

-

What if the number skipped isn't (N-1)? It could be '0' or '2' that's left out. Some visual aids (filled grids) along with your steps would help. (I know, not done that myself - but I didn't end up with a working solution yet either.. ) – Tim Couwelier Jan 15 '16 at 11:08

-

Thanks for the comment. I am trying to add visual aids - the proof I've provided does not require N-1 be skipped - I think that part was edited out because if you keep N-1 and -(N-1) the grid becomes rapidly filled, such that the number of sums produced is about N + N/2, not 2N. I agree that visuals would help. – Jim Jan 15 '16 at 15:45

-

Shouldn't the first $2N-1$ be just $2N$ (e.g. with $N=11$ we want $2\cdot 11=22$ unique sums)? – 2012rcampion Jan 19 '16 at 01:43

-

Thanks for noticing that - I edited that (and a few other things) to help clarify. I'm still trying to figure out useful graphics without making the answer even longer. – Jim Jan 20 '16 at 05:35

I don't know yet

I used a simple backtracking approach. The code is here: https://gist.github.com/smaspe/bb7efc8e03e8eaa81629

It basically tries to recursively fill the matrix and prunes the inconsistent branches as soon as 2 identical sums are found on a complete row or line.

it is currently running.

- 1,116

- 8

- 12

-

-

1I tried changing all the instances of

11to2(for which I know a solution exists, e.g.[[1, 1], [-1, 0]]) and your code returnedNone 13 9instead of a valid grid. – 2012rcampion Jan 06 '16 at 19:54 -

@2012rcampion right. I don't know how I though that was complete. Plenty of things missing... – njzk2 Jan 06 '16 at 20:25

-

@2012rcampion I updated the file. It works for small numbers (however, because it starts by considering

-1, the solution offered for 2 is -1, -1, 0, 1). It is still running for 11, though. – njzk2 Jan 06 '16 at 20:29 -

2Simple backtracking won't be fast enough in Python unless you employ some tricks – qwr Jan 07 '16 at 02:10

-

My best try so far:

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 11

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 -10

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 -1 1 9

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 -1 1 -8

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 -1 1 -1 1 7

-1 -1 -1 -1 -1 -1 0 -1 1 -1 1 -6

1 1 1 1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 5

-1 -1 -1 -1 0 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -4

1 1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 3

-1 -1 0 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -2

0 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 -1 1 0

0 -1 2 -3 4 -5 6 -7 8 -9 10

As you can see, the sum of 1 is missing, instead I end up with 0 twice.

I also suspect that there's a problem with symmetry after one row or column is filled with all 1s or -1s, but I really have no idea how to prove that yet.

- 440

- 2

- 12

- 141

- 3

-

it is always possible to generate such grids for odd $n$ with something like

oddsol[n_] := Table[Flatten@Join[#[[All, t]]] &@{ConstantArray[1, #] & /@ Range[0, n - 1], Join[{0} & /@ Range[(n - 1)/2 + 1], {1} & /@ Range[n/2]], ConstantArray[-1, #] & /@ Reverse@Range[0, n - 1]}, {t, n}]. Then aoddsol@11gives the same as your solution. – martin Jan 12 '16 at 14:37 -

Your build-up can never work. Due to the way it's counted, the 'sum of row sums' and the 'sum of column sums', always have to be equal. This means that the sum of all numbers constructed (which is total of the two previously mentioned sums), by definition is EVEN. This means that from the total you'd have with 23 values (netto being '0'), you can only have an EVEN difference. The number you leave out has to even, and therefor you cannot have a solution leaving out '-11'. And as stated before, -11 and +11 can only co-exist in the grid if both in rows. And out goes your symmetry.. – Tim Couwelier Jan 13 '16 at 07:56

Partial Solution:

We can't have all of {11, -11, 10, -10, 9, -9, 8, -8, 7, -7, 6, -6} in the solution.

Because {11, -11} would obviously have to be in rows (11 in a column and -11 in a row doesn't work since -1 and 1 can't occupy the same place).

This is without loss of generality (because all in columns or all in rows are symmetrical). Call these rows R11 and R-11.

Now {10, -10} have to be in rows as well because there's no room in the remaining columns. Call these rows R10 and R-10.

Similarly {9, -9}, {8, -8} and {7, -7} all have to be in rows. Call these R9, R-9, R8, R-8, R7, R-7

Now we have one row left and the maximum we can put in a column is 5 (using 1 from R10, 0 from R-10, 1 from R9, 0 from R-9, 1 from R8, 0 from R-8, 1 from R7 and 0 from R-7 and then 1 in the remaining empty row). So we have no room left for both 6 and -6.

Therefore we have to get rid of one of {11, -11, 10, -10, 9, -9, 8, -8, 7, -7, 6, -6}.

Say this number is n.

Now the sum of the totals for the rows and the columns is -n.

This is also 2 * (the sum of all the elements in the matrix).

So n must be even, and without loss of generality we can say n = 6, 8 or 10.

Now we need 22 numbers (11x11 matrix) from 23 numbers [-11, 11].

So the numbers are [-11, 11] with 6, 8 or 10 removed.

And the matrix must have R11 and R-11.

Far as I've got.

- 9,431

- 2

- 25

- 49

-

2This is not true, we can have 8 or -8 in columns when 11, -11, 10, -10 and 9, -9 are in rows. – Fimpellizzeri Jan 13 '16 at 23:00

-

@Fimpellizieri You're right! But then R9 and R-9 would have no zeros. And C8 or C-8 would have to use one of the zeros from R10 and R-10. So maybe it goes down to {-11, 11, 10, -10, 9, -9, 8, -8, 7, -7, 6, -6, 5, -5, 4, -4} and we need to lose 10, 8, 6 or 4. I think by this logic we can certainly conclude that we need 0 and have to lose an other even number at the very least. – Paul Evans Jan 13 '16 at 23:45

-

@Fimpellizieri Going to try to stick with a proliferation of zeros as a need to produce both positive and negative lower numbers. Without them you need equal numbers of 1s and -1s before you can start counting. So we can't get the even lower (or otherwise) numbers without at least one zero. – Paul Evans Jan 14 '16 at 00:04

It is not possible if the matrix is odd x odd.

I suspected this by trying the same problem with 4x4 and got a solution: the logic was obvious. There has to be 4+4 distinct numbers, and with -1,0,1 you could find 9 different sums: -4,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,4. There is no solution if you use -4 and 4 at the same time since they have to be in the same row/column. Only solution would be without any of them as below;

So I tried it with 3x3 and 5x5 and I stuck at the same point where you are supposed to put -1,0,1 and there was no possible solution;

Wrote an program that tries to find possible solution with a basic algorithm and it could not find a solution either.

But I can show that it is not possible to have all distinct sums. Firstly, there has to be 22 different numbers and 23 different values you can have by summing rows and columns as states above. First of all I will show you it is not possible to have 11 and -11 at the same time;

If you want to use 11 and -11, there has to be on the same row/column as below;

So you have to have at least one 10 and -10 in this possible solution and you have to put it on the row again since it is not possible to have any of them on a column any more;

So you cannot have -10 any more in this possible solution and you have to use all other possible sums since if you put -1s and one 0 in the row, you will not able to have -9 and 9 any more and there is no way to find a solution any more. So we have to use only one -11 or 11 as below as a start;

since you will have only one 11 or -11, you have to have -10 and 10 at the same time in the solution so only possible solution for this as above.

Then, you need to 9 and -9. You cannot put -9 on the row since you will not able to find 9 any more, so -9 has to be on the column and 9 on the row:

same goes for 8 and -8 and it goes to a point;

So this is the same problem for a oddxodd matrix where you cannot find a solution after this point as 5x5 and 3x3.

As a result, there is no solution and it is not possible!

- 30,307

- 6

- 61

- 215

-

"if you put -1s and one 0 in the row, you will not able to have -9 and 9 any more" - yes you can, if the 0's in the 10 and -10 rows are not in the same column. Also, we already know that if there is a solution, 11 and -11 must be present. – Volatility Jan 18 '16 at 09:01