The recent Supreme Court ruling on this specific case is available. In this instance the court was split 5-4 along Conservative/Liberal lines.

The majority opinion states that Partisan Gerrymandering is outside the jurisdiction of the federal courts.

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the conservative 5-4 majority in Rucho v. Common Cause, admitted that excessive partisan gerrymandering is “incompatible with democratic principles” and “leads to results that reasonably seem unjust.” But, the Court held, challenges to the practice “present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.”

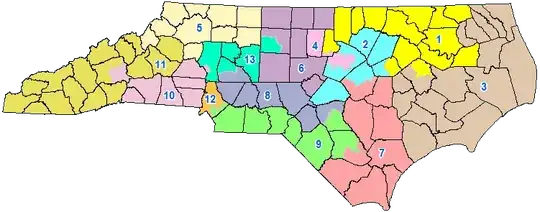

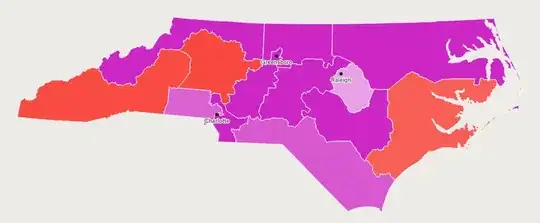

The minority opinion notes that the cases before the court had been subjected to common judicial tests and that both Maryland (Dem) and North Carolina (Rep) had been shown to be Gerrymandered for Partisan political gain.

Applying that test to the North Carolina and Maryland cases, Kagan determined that illegal partisan gerrymandering had occurred in both. “By substantially diluting the votes of citizens favoring their rivals, the politicians of one party had succeeded in entrenching themselves in office,” she wrote. “They had beat democracy.”

So, the short answer to the question would appear to be Yes, North Carolina's (and Maryland's) districts have been gerrymandered for political gain, but that this is (based on a 5-4 ruling) legal within the United States on a federal basis. Whether this is legal on a state level is still an ongoing concern.

The Federal District courts applied the following tests, both cases failed these tests and were judged to be Partisan Gerrymandering.

Kagan cited the three-part test the federal district courts in North Carolina and Maryland, and other courts around the country, used to decide vote dilution claims. The test examines intent, effects and causation. First, plaintiffs must show that the state officials’ “predominant purpose” in drawing district lines was to “entrench [their party] in power” by diluting the votes of the rival party. Second, plaintiffs must establish that the lines drawn “substantially” diluted their votes. Third, the burden shifts to the State to posit a “legitimate, non-partisan justification to save its map.”

The full opinion of the lower court is available, and appears to set the affect of dilution at 19.4%, but the precise meaning of this is not something I currently understand.