In addition to the above answer, the following might be worthwhile too.

Often, an algorithm for one scheduling problem can be applied to another scheduling problem as well. For example, $ 1|| \sum c_{j} $ is a special case of $ 1|| \sum w_{j}c_{j} $ and a procedure for this can also be used for the first one. In complexity terms, it is said that $ 1|| \sum c_{j} $ reduces to $ 1|| \sum w_{j}c_{j} $. Based on this concept a chain of reductions can be established. For example:

$$ (1|| \sum c_{j}) \rightarrow (1|| \sum w_{j}c_{j}) \rightarrow (P_{m} || \sum w_{j}c_{j}) \rightarrow (Q_{m} |prec| \sum w_{j}c_{j}))$$

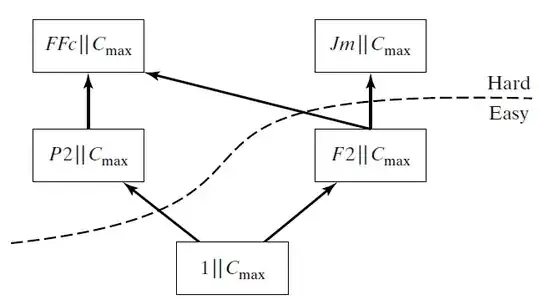

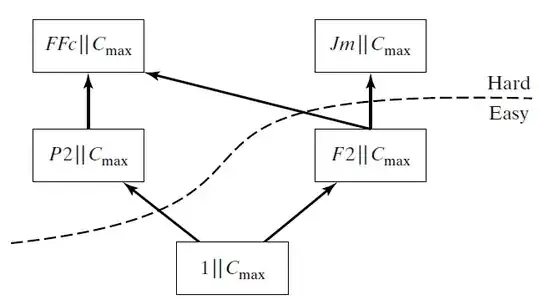

As an example of hard and easy problem, $ 1 || C_{max} $, $ P_{2} || C_{max} $, $ F_{2} || C_{max} $, $ J_{m} || C_{max} $, and $ FF_{c} || C_{max} $:

Of course, there are also many problems that are not comparable with one

another. For example, $ P_{m} || \sum w_{j}T_{j}$ is not comparable to $ J_{m}|| C_{max} $.

A considerable effort has been made to establish a problem hierarchy describing

the relationships between the hundreds of scheduling problems. In the

comparisons between the complexities of the different scheduling problems, it

is of interest to know how a change in a single element in the classification of

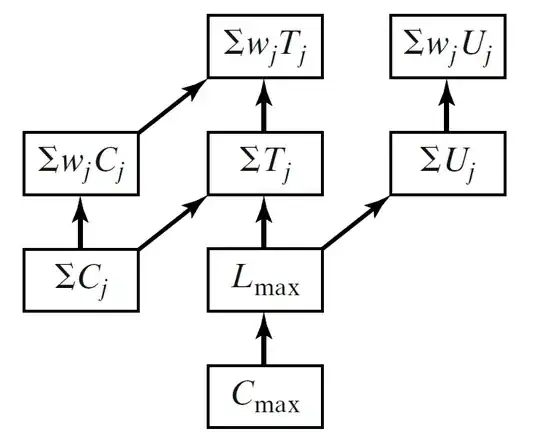

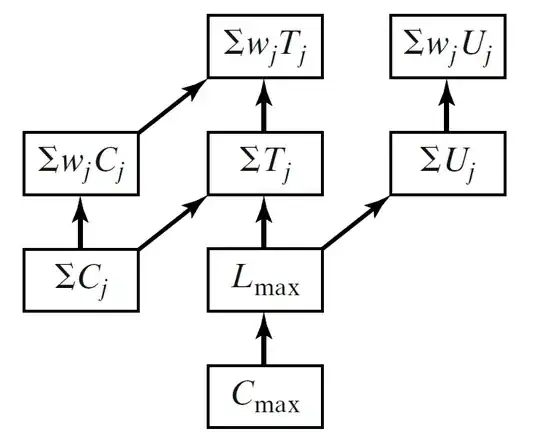

a problem affects its complexity. The following graph helps determine the complexity hierarchy of deterministic scheduling problems based on the different objective functions.