Summary

$\DeclareMathOperator*{\argmin}{\arg\!\min}$It turns out that, for any $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, $g_u$ is minimized with respect to $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ when $f(x_i) = F^*$ for $i = 1,\dots,m$, where $F^* = \min_x f(x)$. Moreover, $f$ is not required to be convex, but is instead required to have at least one global minimum such that $F^*$ exists (for example, $f(x) = -\exp(-x^2)$ has one global minimum at $x=0$, but it is neither convex nor concave on $X = \mathbb R$). This includes the cases when $f$ has a countable and uncountable number of global minima. Therefore, for the same choice of $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, the optimization problem

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m})

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

is equivalent to the optimization problem

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & \forall i \in \{1,\dots,m\}, f(x_i) = F^*

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

We now discuss the details of this for the case when $f$ has a single global minimum, a countable number of global minima, and an uncountable number of global minima.

Single global minimum

First, suppose that $f : X \to \mathbb R$ has exactly one global minimizer $z^* \in X$, such that $f(z^*) \leq f(x)$ for every $x \in X$. Second, fix any $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$. Then, note that

$$

\begin{align}

\min_{x_{1:m}} g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) &= \min_{x_{1:m}} \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot f\left(x_i\right) \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot \min_{x_i} f\left(x_i\right) \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot f(z^*) \\

&= f(z^*) \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \\

&= f(z^*)

\end{align}

$$

and so, for any $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, $\argmin_{x_{1:m}} g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) = (z^*,\dots,z^*)$. Then, for the same choice of $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, note that

$$

g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) = f\left(\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot x_i\right)

$$

is minimized when

$$

\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot x_i = z^*

$$

For this choice of $\alpha_{1:m}$, there are infinitely many values of $x_{1:m} \in X^m$ for which this equation is satisfied. However, we are looking for the unique $x_{1:m}$ such that $g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m})$ is also minimized. We have already established above that this occurs when $x_{1:m} = (x_1,\dots,x_m) = (z^*,\dots,z^*)$. By plugging this into the equation above, we get

$$

\begin{align}

\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot z^* &= z^* \\

z^* \cdot \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i &= z^* \\

z^* &= z^*

\end{align}

$$

and so $x_{1:m} = (z^*,\dots,z^*)$ is the unique minimizer of both $g_\ell$ and $g_u$. That is, the solution to the optimization problem

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & \forall i \in \{1,\dots,m\}, x_i = z^*

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

is equivalent to the solution to the optimization problem

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m})

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

for every $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, where $z^*$ is the global minimizer of $f$.

Alternatively, in the case when determining $z^*$ directly is difficult, we could also solve the following equivalent optimization problem

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & Ax = 0

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

where $x \in \mathbb R^{nm}$ is the block vector

$$

x = \begin{bmatrix}x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_m\end{bmatrix} \tag{1}

$$

and $A \in \mathbb R^{n(m-1) \times nm}$ is a block matrix such that its $(i,j)$ element is

$$

A_{ij} = \begin{cases}I, & i = j \\ -I, & i = j - 1 \\ 0, & \text{otherwise}\end{cases} \tag{2}

$$

where $I$ is the $n \times n$ identity matrix and $0$ is the $n \times n$ zero matrix. The $Ax = 0$ constraint is equivalent to the following set of constraints:

$$

\{x_i = x_j \mid \forall (i,j) \in \{1,\dots,m\}^2,i = j-1\}

$$

The reason that this optimization problem is equivalent to the previous one is that the constraint $\forall i \in \{1,\dots,m\}, x_i = z^*$ in the previous problem is an element of the feasible set induced by the constraint $Ax = 0$, and that this element is a global minimizer of $g_\ell$.

Example

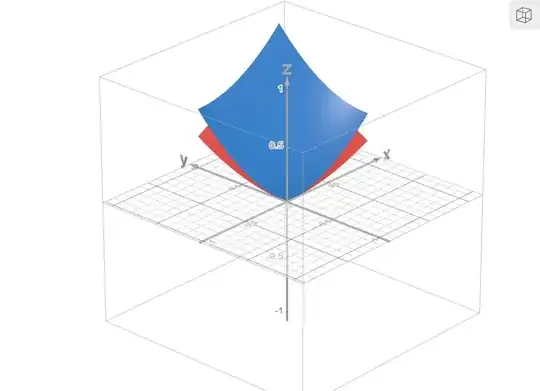

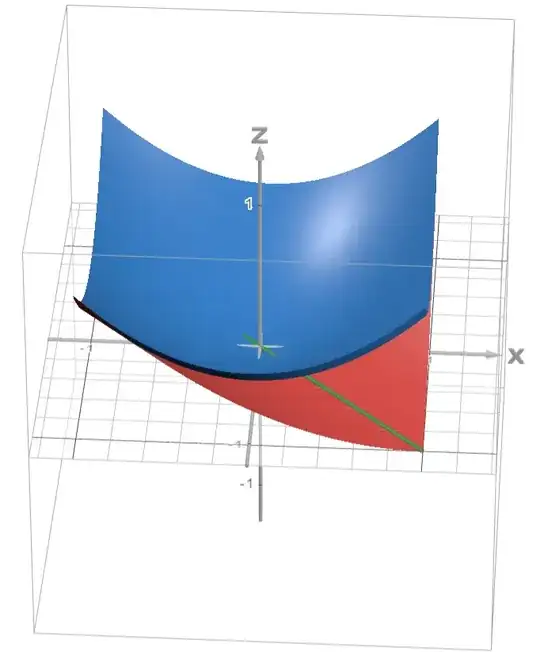

To verify the preceding arguments, consider the example where $X = [-1,1]$, $f(x) = x^2$, and $g_\ell : [-1,1]^2 \to \mathbb R$ and $g_u : [-1,1]^2 \to \mathbb R$ are defined as

$$

\begin{align}

g_\ell(x_1,x_2) &= \left(\alpha \cdot x_1 + (1-\alpha) \cdot x_2\right)^2 \\

g_u(x_1,x_2) &= \alpha \cdot x_1^2 + (1-\alpha) \cdot x_2^2

\end{align}

$$

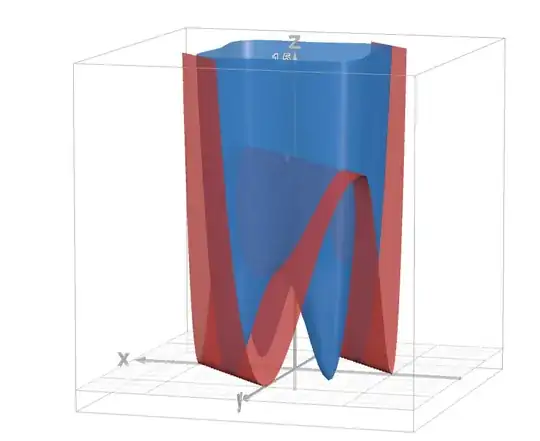

where $\alpha \in [0,1]$. The global minimum of $f$ occurs at $0$. We plot $g_\ell$ (red) and $g_u$ (blue) in the figure below for $\alpha = 0.5$, where we also show the line $\alpha \cdot x_1 + (1-\alpha) \cdot x_2 = 0$ in green. We see that both $g_\ell$ and $g_u$ are minimized when $(x_1,x_2) = (0,0)$ as expected.

Countable number of global minima

We now consider the case when $f$ has a countable number of global minima. Let the unique global minimizers of $f$ be $z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*$ for $K > 1$ and $K \in \mathbb N$, such that $f(z_1^*) = \cdots = f(z_K^*) = F^* \in \mathbb R$ and $f(z_i^*) \leq f(x)$ for every $x \in \mathbb R^n$ and $i = 1,\dots,K$. As before, we want to determine the cases when the minimizers of $g_\ell$ and $g_u$ are equivalent for any $\alpha_{1:m}$. We proceed as follows. First, fix any $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$. Then,

$$

\begin{align}

\min_{x_{1:m}} g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) &= \min_{x_{1:m}} \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot f\left(x_i\right) \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot \min_{x_i} f\left(x_i\right) \tag{3} \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot F^* \\

&= F^* \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \\

&= F^*

\end{align}

$$

Unfortunately, because $K > 1$, we can no longer conclude that $\argmin_{x_{1:m}} g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) = (z^*,\dots,z^*)$ for every $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$ as before. The reason is that $F^*$ is achieved by $K$ different minimizers of $f$. Moreover, because $(3)$ above consists of a convex combination of $\min_{x_i} f(x_i)$, then we can choose one of $K$ minimizers for each of the $m$ elements in this combination. So, there exist a total of $K^m$ global minimizers for $g_u$, each achieving the minimum $F^*$. The set of all of these global minimizers is

$$

\{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}^m = \underbrace{\{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\} \times \cdots \times \{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}}_{\text{$m$ times}}

$$

Then, for the same choice of $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, note that

$$

g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) = f\left(\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot x_i\right)

$$

is minimized when any one of the following $K$ equations is satisfied:

$$

\begin{align}

\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot x_i &= z_1^* \\

&\vdots \\

\sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot x_i &= z_K^*

\end{align} \tag{4}

$$

As before, there are infinitely many values of $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ for which one of the $K$ equations in $(4)$ is satisfied. That is, for this choice of $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$, the values of $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ that minimize $g_\ell$ all lie on the $K$ $n$-dimensional lines defined by the $K$ equations in $(4)$.

However, we are looking for the values of $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ such that $g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m})$ is also minimized. We have already established above that this occurs when $x_{1:m} \in \{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}^m$. Therefore, we search for $x_{1:m} \in \{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}^m$ such that one of the $K$ equations in $(2)$ is satisfied. In the set $\{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}^m$, there are two kinds of points $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ that satisfy one of the equations in $(4)$:

- If for each $z_j^* \in \{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}$, $z_j^*$ is not in the convex hull of $z_1^*,\dots,z_{j-1}^*,z_{j+1}^*,\dots,z_K^*$ (i.e. $z_j^*$ cannot be expressed as a convex combination of $z_1^*,\dots,z_{j-1}^*,z_{j+1}^*,\dots,z_K^*$), then there are only $K$ points defined as $(x_1,\dots,x_m) = (z_i^*,\dots,z_i^*)$ for $i = 1,\dots,K$ that satisfy one of the equations in $(4)$.

- However, if there exist $z_j^*$ that are in the convex hull of $z_1^*,\dots,z_{j-1}^*,z_{j+1}^*,\dots,z_K^*$, such that $$\alpha_1 z_1^* + \dots + \alpha_{j-1}z_{j-1}^*,\alpha_{j+1}z_{j+1}^*,\dots,\alpha_{K}z_K^* = z_j^*$$ then, in addition to the $K$ points defined as $(x_1,\dots,x_m) = (z_i^*,\dots,z_i^*)$ for $i = 1,\dots,K$, there are other points in $\{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}$ that satisfy one of the equations in $(4)$. These are the points that, when combined as a convex combination, yields $z_j^*$.

In both cases, the $K$ points defined as $(x_1,\dots,x_m) = (z_i^*,\dots,z_i^*)$ for $i = 1,\dots,K$ will minimize both $g_\ell$ and $g_u$.

Therefore, we can proceed in one of two ways.

Solution method 1

We solve the following integer program:

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & (x_1,\dots,x_m) \in \{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}^m

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} \tag{5}

$$

which is equivalent to solving

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & (x_1,\dots,x_m) \in \bigoplus_{i=1}^K \left\{(x_1,\dots,x_m) \in \mathbb R^{n \times m} \Bigg| \sum_{j=1}^m \alpha_j \cdot x_j = z_i^*\right\}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} \tag{6}

$$

where the $\oplus$ symbol represents the exclusive OR operation on the $K$ sets. We can re-write $(6)$ as an integer program as follows. Define the binary variables $y_1,\dots,y_K$, such that $y_i \in \{0,1\}$ for $i = 1,\dots,K$. Then, $(6)$ can be re-written as

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & \forall i \in \{1,\dots,K\}, y_i \in \{0,1\} \\

\quad & \sum_{i=1}^K y_i = 1 \\

\quad & \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot x_i = \sum_{j=1}^K y_j \cdot z_j^*

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} \tag{7}

$$

There are two disadvantages of this solution method. The first one is that the constraints imposed in $(5)$ and $(7)$ will result in the need to solve integer programs, which are difficult in general. This may or may not be important in practice. We relax this difficulty in solution method 2 below.

The second disadvantage is that the solution $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ that we obtain from $(5)$ will not necessarily be equal to the solution obtained from $(7)$. The reason is that any one of the $K^m$ solutions that solve $(5)$ will also solve $(7)$. Therefore, we can pick one of these solutions to solve $(5)$ and a different one to solve $(7)$. Although the solutions $(x_1,\dots,x_m)$ obtained from $(5)$ and $(7)$ will necessarily minimize both $g_\ell$ and $g_u$, they will not necessarily be the same.

Solution method 2

Because the $K$ points defined as $(x_1,\dots,x_m) = (z_i^*,\dots,z_i^*)$ for $i = 1,\dots,K$ will necessarily minimize both $g_\ell$ and $g_u$, then instead of solving $(5)$, we solve

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & (x_1,\dots,x_m) \in \{(z_1^*,\dots,z_1^*),\dots,(z_K^*,\dots,z_K^*)\}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

or equivalently

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_\ell(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & Ax = 0

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} \tag{8}

$$

where the block matrix $A$ and the block vector $x$ are defined as in $(1)$ and $(2)$ above. Solving $(8)$ is equivalent to solving

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & (x_1,\dots,x_m) \in \{(z_1^*,\dots,z_1^*),\dots,(z_K^*,\dots,z_K^*)\}

\end{aligned}

\end{equation}

$$

or equivalently

$$

\begin{equation}

\begin{aligned}

\min_{x_{1:m}} \quad & g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}), \\

\textrm{s.t.} \quad & Ax = 0

\end{aligned}

\end{equation} \tag{9}

$$

where the block matrix $A$ and the block vector $x$ are defined as in $(1)$ and $(2)$ above. Compared to solution method 1, the advantage of solution method 2 is that we are no longer solving integer programs, as the constraints in $(8)$ and $(9)$ are linear. However, the disadvantage of solution method 2 compared to solution method 1 is that not all the valid solutions can be obtained by solving $(8)$ and $(9)$. This is because the feasible sets in $(8)$ and $(9)$ are restricted to $\{(z_1^*,\dots,z_1^*),\dots,(z_K^*,\dots,z_K^*)\}$, which is a subset of the larger solution set $\{z_1^*,\dots,z_K^*\}^m$.

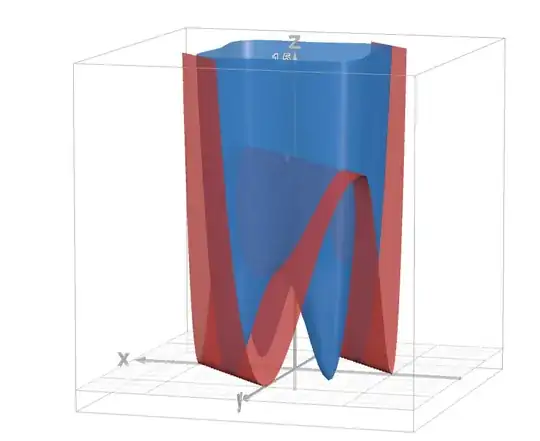

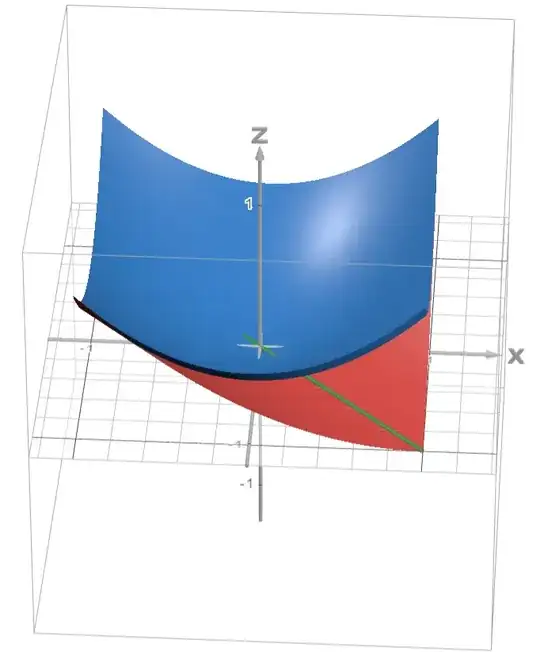

Example

To verify the preceding arguments, consider the example where $X = [-2,2]$, $f(x) = (x-1)^2(x+1)^2$, and $\alpha = 0.5$. The global minima of $f$ occur at $x = -1,1$, which implies that the global minima of $g_u$ occur at $(-1,-1),(1,-1),(-1,1),(1,1)$.

We plot $g_\ell$ (red) and $g_u$ (blue) in the figure below. We see that, as expected, $g_u$ has four global minima: $(x_1,x_2) = (1,1),(-1,1),(1,-1),(-1,-1)$. Both $g_\ell$ and $g_u$ are minimized when $(x_1,x_2) = (-1,-1),(1,1)$.

Uncountable number of global minima

Finally, we consider the case when $f$ has an uncountable number of global minima. Let the unique global minimizers of $f : X \to \mathbb R$, where $X \subseteq \mathbb R^n$, be parameterized by the curve $z^* : [0,1] \to X$ (note that $[0,1]$ and $\mathbb R$ have the same cardinality), such that $f(z^*(t)) = F^* \in \mathbb R$ for every $t \in [0,1]$ and $F^* \leq f(x)$ for every $x \in X$. As before, we want to determine the cases when the minimizers of $g_\ell$ and $g_u$ are equivalent for any $\alpha_{1:m}$. We proceed as follows. First, fix any $\alpha_{1:m} \in \Delta$. Then,

$$

\begin{align}

\min_{x_{1:m}} g_u(x_{1:m},\alpha_{1:m}) &= \min_{x_{1:m}} \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot f\left(x_i\right) \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot \min_{x_i} f\left(x_i\right) \\

&= \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \cdot F^* \\

&= F^* \sum_{i=1}^m \alpha_i \\

&= F^*

\end{align}

$$

In this case, because $F^*$ is achieved by an uncountable number of different minimizers of $f$ that are parameterized by $z^*$, then $g_u$ also has an uncountable number of global minimizers. If we denote $A \subseteq X$ as the range of $z^*$ (i.e. $A = \{z^*(t) \mid t \in [0,1]\}$), then the set of all global minimizers of $g_u$ is $A^m$. It turns out that the rest of the derivation for the uncountable case is similar to the countable case, so we leave it to the reader to fill in the blanks.