First of all, these two statements are made in sequence, not parallel (credit to MSalters for crystallizing this point):

Generally speaking, the absence of a license means that the default copyright laws apply.

...if you publish your source code in a public repository on GitHub... you allow others to view and fork your repository.

- The first statement is a general statement about copyright law.

- The second statement is about a license grant required by the GitHub Terms of Service.

They are both true, and if you host your code on GitHub, the second, specific statement takes precedence over the first general rule wherever the second rule applies. The second statement is a notice that hosting on GitHub requires you to make certain license grants to GitHub users which differ from the default rules of copyright.

Below is an inspection of what the "right to fork" could possibly mean, which will clarify the question: "What's the license of the new fork?"

(This is not legal advice. Furthermore, this is barely regular advice, and is based on a speculative -- but coherent -- reading of some ambiguity in the GitHub TOS.)

Here's what the GitHub Terms of Service has to say about forking:

By setting your repositories to be viewed publicly, you agree to allow others to view and fork your repositories.

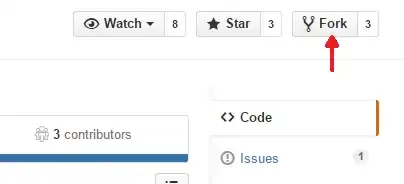

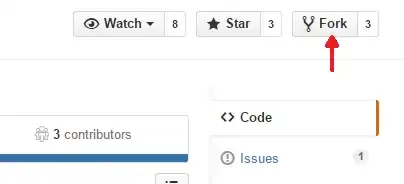

The term "fork" is not defined anywhere in the GitHub Terms of Service, but it seems perfectly sensible to assume that "fork" here is meant in the sense that it is used elsewhere on github.com: the Fork button.

GitHub probably intends "the right to fork" to mean "the right to use the Fork feature of the github.com website." In this case, "creating a fork" would not mean generally creating a copy or derivative work (as it does in general FLOSS parlance), but rather it means triggering the software of github.com to create and host a verbatim copy of a repository and categorize that copy under the user's list of forks.

If the original copyright owner doesn't license any other permissions, clicking that button is all that the TOS-required permission allows the user to do. This doesn't grant any rights to create a derivative work, or to redistribute the code outside of github.com, since the "Fork" feature is intrinsic to the github.com website.

Speculation: this right-to-fork language in the GitHub TOS was probably included to prevent legal issues around the use of the Fork feature. The intent was likely something to the effect of, "You must license the minimum amount of rights to allow github.com's Fork software feature to operate."

Based on this reading of "fork," if another user were to use a github.com-hosted forked-repository to prepare and distribute a derivative work, that would infringe on the owner's copyright, since such an action is outside the scope of the Fork software feature. Similarly, if the user were to create a verbatim copy outside the context of github.com's Fork functionality (e.g. copying the code to another website), that would also not be permitted. The TOS does not allow the right to create copies generally; it only requires the author to grant copying permission inasmuch as copying is a necessary component of the Fork feature.

(All that said, this is speculative based on a specific reading of "fork." I'd like to say, on a personal note, it is kind of ridiculous that the GitHub Terms of Service use "fork" without a shred of definition to be seen.)